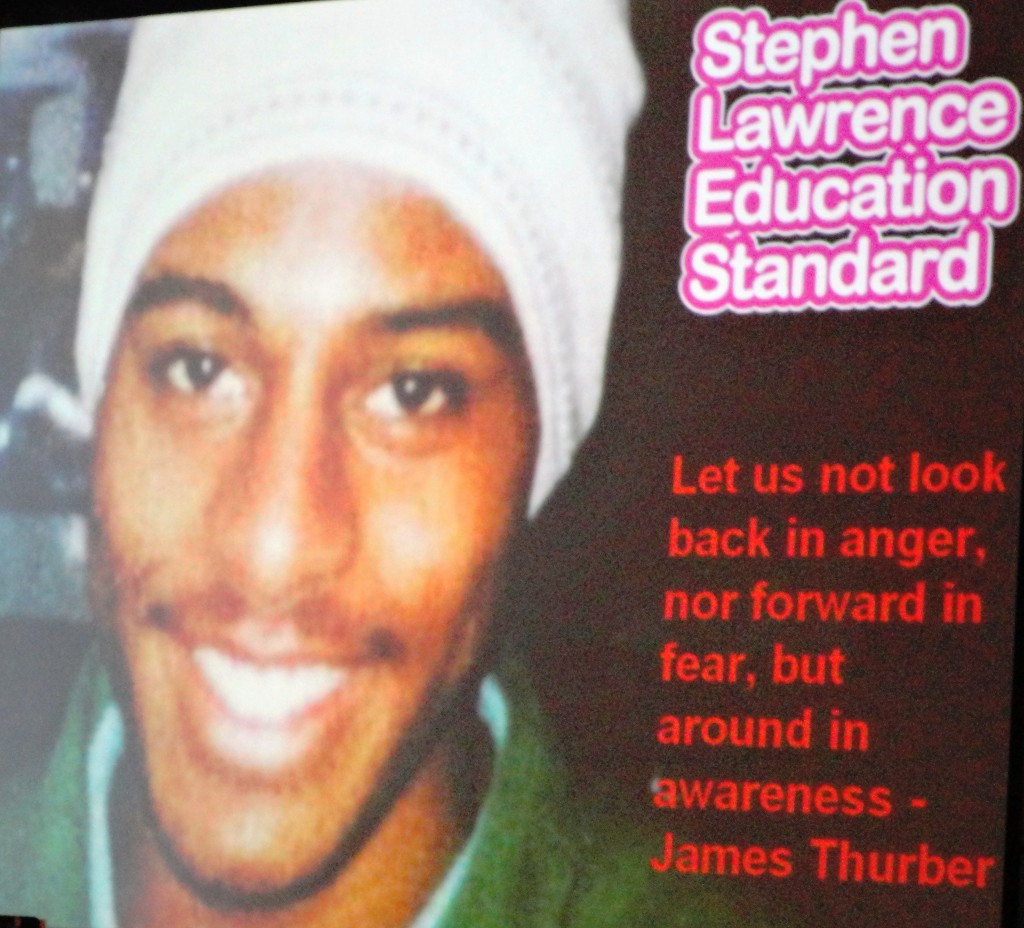

Stephen Lawrence, Lord MacPherson and Sergeant XX The Anti-Imperialist

New in Ceasefire, The Anti-Imperialist - Posted on Tuesday, December 20, 2011 12:00 - 4 Comments

The extremely vicious and disturbing racist language used by those suspected of murdering Stephen Lawrence has been rightly condemned by a range of newspapers and broadcasters. Just over a year after the murder, the suspects were recorded using the most depraved language while recalling past racial attacks they had engaged in, as well as threatening acts of the most destructive terror on peoples of African and Asian descent living in Britain. The re-emergence of this story into the mainstream press draws attention to the issue of hate crime in Britain, still a huge problem for many communities.

However, few, if any, of the news stories bothered to ask why an event which took place in 1993 is still being investigated 18 years after that fateful moment when Stephen Lawrence looked over his shoulder to hear a group of white men shouting “What, what N****r!” before attacking and stabbing him to death.

The Stephen Lawrence inquiry, and the subsequent MacPherson Report, did not primarily intend to draw attention to the hate crimes carried out by civilians against victims such as Lawrence and countless others. Instead, they were damning indictments of an institutionally racist police force, thus providing the evidence that Black communities had waited decades for. What the campaign, and the subsequent inquiry did, was to bring under the light how the UK police force in this country engages with people of African and Asian descent.

Indeed, the press releases have described the investigation into Stephen’s murder as ‘a sequence of disasters and disappointments’. However, this passive language is often used when describing police corruption, discrimination or abuse, to create the impression of some kind of natural catastrophe, rather than premeditated collusion and endemic racism. As a result, few people are aware of the overwhelming evidence which led Lord Macpherson and his team to conclude that there can be no doubt that the Metropolitan Police Service is institutionally racist.

Statements from the Lawrence family about the way in which they were treated by police also reflect the experiences of many Black people criminalised by the law enforcement establishment. The treatment of Duwayne Brooks, who was with Stephen during the attack but had managed to get away and call an ambulance, was never asked by police if he had been attacked.

What he was asked, however, was whether he had been carrying a weapon, insisting that he knew who had attacked Stephen. Police also repeatedly asked Brooks what he and Stephen had done to provoke the attack which led to his friend being stabbed to death. They then asked him if he and Stephen had been harassing white girls outside the local McDonalds earlier that evening. They did not even allow Duwayne to travel in the ambulance with his dying friend.

Less than an hour after the attack, a carload of young white males drove past twice, cheering. They were identified as Jason Goatley and David Copley – both of whom were involved in an attack, two years earlier, that led to the murder of Rolan Adams. Also in the car was Kieran Highland, an influential member of an organisation called Nazi Turn Out. No attempt to pursue the vehicle or these individuals in connection with the attack on Lawrence was ever made.

Within days of Stephen’s murder, a number of anonymous witnesses cited two members of a knife-carrying and bullying gang, who had been involved in racially motivated attacks on other Black individuals in the past, as possible suspects in the stabbing of Stephen Lawrence.

Within days of Stephen’s murder, a number of anonymous witnesses cited two members of a knife-carrying and bullying gang, who had been involved in racially motivated attacks on other Black individuals in the past, as possible suspects in the stabbing of Stephen Lawrence.

Another witness visited the Lawrences’ home to tell them the names of people she saw washing blood off their clothes the day after the murder. And yet, these witnesses and a myriad of others were actively ignored by the Metropolitan Police.

The stories dominating headlines portrayed this failure as incompetence. Few recent reports have sought to re-address institutional racism at the root of the Lawrence tragedy, and fewer still the serious allegations of corruption and collusion between police and suspects.

The first issue with the investigation is that the Senior Investigating Officer at the time, Ian Crampton, took three weeks to make any arrests, despite numerous tip-offs including drop-ins at the station, phone messages, the aforementioned visitor to the Lawrence home and a note left on the windscreen of a police car.

Further to this, no e-fit or identity parades took place, despite Duwayne Brooks providing a detailed description of at least one of the suspects. Ian Crampton insists that this was a strategic decision, although no records show any reference to a discussion or indeed any reference to this ‘strategy’ being decided upon.

One of the prime suspects, 17 year old David Norris, is the son of a well-known criminal called Clifford Norris who, as the Inquiry confirmed, “is said to have become positively and corruptly involved” in the bribing and/or threatening of witnesses in the investigation of the stabbing of Stacey Crampton.

During the Lawrence investigation, Ian Crampton had also been pursuing another case: the murder of another man named Clifford Norris, an informant who claimed to be a relative of his infamous, better-known namesake. Needless to say, we can be certain that the Norris family were a group of people whom Mr Crampton, as the Senior Investigating Officer in the Lawrence case, was very much aware of.

What is worrying, therefore, is that Mr Crampton denies making any link at the time between David Norris, the prime suspect in the murder of Stephen Lawrence, and Clifford Norris, his father, who was suspected of bribing/intimidating witnesses in a previous case his son was involved in.

Although these events are suspicious enough, the introduction of another officer, identified only as ‘Officer XX’, into the frame deepens the likelihood of corruption even further. And makes police collusion with the organised criminals and racists attackers of Stephen Lawrence even more apparent.

Customs & Excise officers had been monitoring Clifford Norris for a number of months, due to his connections with the shipment and sale of criminalised drugs. During the surveillance, Officer XX was “seen on four occasions in company with one or both of the Norrises”, the prime suspect of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, and his father, drinking in London pubs. However, rather than this relationship being investigated, Sergeant XX was given a verbal warning, and was never subjected to a charge under the disciplinary code.

What the Inquiry finds next adds further weight to the suspicious nature of Sergeant XX’s involvement, as well as that of Mr Crampton:

“A connection between Sergeant XX and Mr Crampton was apparently known to his supervisors before this Inquiry, and emerged in the course of the evidence of Mr Crampton. It was discovered from the complaints file in connection with Sergeant XX that Mr Crampton had given reference to the Disciplinary Board which dealt with Sergeant XX in 1989. That reference is in the form of a written statement, setting out a ‘professional’ reference indicating that in Mr Crampton’s view the officer was to be commended for his work, and indeed for his honesty during the time when he served under Mr Crampton in 1987. At that time Sergeant XX was stationed in south-east London, and he was serving immediately under Mr Crampton.”

“A connection between Sergeant XX and Mr Crampton was apparently known to his supervisors before this Inquiry, and emerged in the course of the evidence of Mr Crampton. It was discovered from the complaints file in connection with Sergeant XX that Mr Crampton had given reference to the Disciplinary Board which dealt with Sergeant XX in 1989. That reference is in the form of a written statement, setting out a ‘professional’ reference indicating that in Mr Crampton’s view the officer was to be commended for his work, and indeed for his honesty during the time when he served under Mr Crampton in 1987. At that time Sergeant XX was stationed in south-east London, and he was serving immediately under Mr Crampton.”

Eventually, Sergeant XX was disciplined for making false entries into his duty state (which is supposed to provide an account of his actions on a day-to-day basis). It was revealed that Sergeant XX was absent from duty when he was supposedly in court. This took place during the same period that he was caught in a number of London pubs having drinks with the Norrises. As Michael Mansfield QC, representing the Laurence family, asserts: “There is a matrix of quite exceptional coincidences and connections here which weave such a tight web around this investigation that only an ability to suspend disbelief can provide an innocent explanation”.

The MacPherson Report’s indications do not point towards a simple case of police corruption and collusion with criminal gangs. Instead, they show a close relationship between violent white supremacist groups that have been terrorising Black communities, and an institutionally racist police force. In addition to drawing inevitable conclusions about the shocking links between racist gangs in London and a police force that turned out to also be institutionally racist, we must also see these two manifestations of white supremacy as both intrinsically linked, and mutually re-enforcing.

Indeed, it is the system of white supremacy, in which we were all born, and which permeates our daily lives that has inevitably, and systemically, led to gangs (both criminalised and state-backed) becoming involved in Stephen Lawrence’s murder and its aftermath. Only by addressing the power structures giving rise to both the overt and institutionalised racisms plaguing our communities can we fully address the issues which have led to a heinous murder, committed 18 years ago, still being contested as we speak.

4 Comments

happy smiles

[…] patting each other on the back for finally ‘securing justice’ for Stephen Lawrence? Indeed, throughout the Lawrence trial, institutional racism was rarely mentioned and when it was little analysis was produced. The […]

When someone writes an article he/she maintains the thought of a user in his/her mind that how a user can understand it. So that

Doreen Lawrence, police spies and institutional racism By Adam Elliott-Cooper |

[…] was certainly receiving poor treatment due to the racialised nature of the case, and there was evidence that police officers had personal links with the criminal families involved in the murder of […]

“the evidence that Black communities had waited decades” – the evidence was always there in our lived realities but for some people a bubble it broke… for a moment…

“the experiences of many Black people criminalised by the law enforcement establishment” – that includes MPs, judges, sociltors and police officers…

But what you don’t state explicitly is that while racism permeates our way of life in diverse and unexplored ways, within elite hierachical organisations the possibilities for institutional racism present a formula that cannot simply be restructured but needs to be first held to account and dismantled.