Paint them black: the riots and mass incarceration Books

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Sunday, September 25, 2011 14:00 - 5 Comments

By Jonathan Jacobs

By Jonathan Jacobs

It has widely been noted that one overriding theme has presided over the media coverage of the riots: bestiality. The rioters are ‘feral’, ‘mindless’ ‘thugs’ and their criminal behaviour is (quoting Kenneth Clarke) governed by ‘instinct’. Any break from this lexis of base criminality in media coverage is subjected to swift censure – recently the BBC was forced into an embarrassing climbdown over its use of ‘protesters’ instead of the acceptable ‘scum’ or ‘hooligans’.

Why is ‘scum’ and its synonyms such a popular and useful lexicon for the media?

Many reasons. One, it closes to a great extent debate on the causes of the riots. These rioters are not the product of remediable social injustice; they are innately, animalistically malevolent, and the proper treatment for dangerous animals is control, a stern hand. This vaguely defined bogeyman of a lawless underclass has so diverted attention from the root issues of the unrest as to actually make the riots a PR coup for the Metropolitan Police (who got thousands of ‘likes’ on Facebook as a result.)

But more importantly, the utility of ‘scum’ is that it doesn’t openly discriminate, except on the basis of criminality – which is an acceptable prejudice. ‘The riots are not about race’, said Cameron, they are about ‘thugs’. It is only when someone in the media breaks from the script that the real implications of ‘scum’ come to the surface.

Like Darcus Howe’s thundering response to a BBC interviewer’s gaffe, where the archaic racial epithet ‘negro’ broke the surface of official impartiality. Or when David Starkey evoked Enoch Powell to argue that ‘the whites have become black’. Both instances made uncomfortably explicit the implicit collocation of race and criminality in this euphemistic ‘feral underclass’. David Starkey defended his comments, arguing that he was only saying what everyone was thinking but was too afraid to say. In this respect, he has perversely been among the more astute commentators on the riots.

Because these riots are about race. The unrest emerged from a context of frustration, anger, injustice which is profoundly racialised. The murder of yet another unarmed black man by police. A stop-and-search policy that targets black and brown people at six times the rate of whites. A systematic dismantlement of public services and state support for the socially disadvantaged, a category that is disproportionately non-white.

This is not to say that the riots are just about race. Indeed, the much-emphasised diversity of the ‘looter’ attests to the spectrum of injustice young people of all races suffer from stop and search, budget cuts, and so on. But far from being a cause for optimism, such diversity merely demonstrates the increasing sophistication of marginalisation.

The media’s bogeyman of a ‘feral undercaste’ isn’t explicitly racial. But it is defined by the very same signifiers – bestiality, ignorance, inherent criminality – that have historically informed systems of racial control, from colonialism to apartheid and the ‘war on terror.’

The paradigm of civilisation versus barbarianism that this feral underclass conjures cannot be dissociated from race. It strongly recalls the reaction to the Bradford riots in 2001 – in particular, David Blunkett’s infamous description of the jailed Asian men as ‘mindless maniacs’, followed by an insistence that ‘ethnic origin has nothing to do with it’. Both riots were also marked by shocking and disproportionate sentencing. In Bradford, rioters with no previous convictions were jailed for 6 years; in the recent unrest a man got 16 months for stealing an ice cream.

In 2011, the face of civilisation is the defiant, Blitz-spirited and largely white ‘Riot Wombles’, while the poster-child for disorder is the black guy who tweeted a picture of himself in front of his stolen goods – ‘brazen!’ captions The Daily Mail.

But race in this context has a less stable locus than skin colour. It is, as David Starkey suggested, a sort of infection – even a white person can become black if they aren’t careful, according to the new parameters of the social outcast, and the process through which a young white person ‘becomes black’ is the process of becoming a criminal. The association of ‘blackness’ with criminality is now so embedded that you don’t even have to be black to be ‘black’.

It would be a serious mistake to see, as some on the left have, the widening of this category of ‘blackness’ in Britain as indicating some kind of progression. In fact, the opposite is more the case: the strokes by which the alien is defined in our society have become (though still highly racialised) broader, with the effect that the exclusionary rhetoric of European racism – bestiality, scum, unreformable, barely human, and so on – has become so embedded that its signifiers can now be applied to delegitimise any form of dissent.

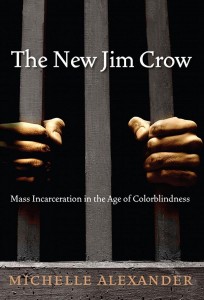

Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow offers timely commentary on the ‘colouring’ of criminality. It discusses the explosion in prisoner numbers in the US over the last two decades, of which an overwhelming proportion are black or brown, and she convincingly argues that the mass imprisonment of African-Americans since the inauguration of ‘The War on Drugs’ in the 1980s amounts to a system of racialised social control akin to Jim Crow. American policy on drugs is officially colourblind – it can discriminate only on the basis of criminality – but it is designed and enforced to ensure that the drug criminal is almost always black or brown.

Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow offers timely commentary on the ‘colouring’ of criminality. It discusses the explosion in prisoner numbers in the US over the last two decades, of which an overwhelming proportion are black or brown, and she convincingly argues that the mass imprisonment of African-Americans since the inauguration of ‘The War on Drugs’ in the 1980s amounts to a system of racialised social control akin to Jim Crow. American policy on drugs is officially colourblind – it can discriminate only on the basis of criminality – but it is designed and enforced to ensure that the drug criminal is almost always black or brown.

This ‘New Jim Crow’ begins at the level of drug legislation. There is an enormous disparity in the punishment of cocaine offences relative to its form. Under federal law, powder cocaine (the expensive, ‘white’ form of the drug) is punished one hundred times less severely than crack cocaine, convictions for which are overwhelmingly black.

Someone caught selling five hundred grams of powder can expect five years in prison; just five grams of the black version will land you the same sentence, despite no convincing evidence that crack is any more dangerous than powder.

It continues with enforcement. Stop-and-search tactics are disproportionately – even exclusively – conducted in black or Latino areas, despite the fact that whites are statistically more likely to sell and abuse drugs.

It carries through to sentencing level, where the black drug offender will on average receive a heavier punishment than his white counterpart, even if the offence is identical, and where it is not unlikely he will be tried by an all-white jury: prosecutors frequently prevent black people from serving on juries for such ‘race-neutral’ reasons as wearing baggy jeans or ‘gang hairstyles’, and coming from a ‘bad neighborhood’.

Routes for appeal on grounds of discrimination are entirely blocked. The criminal justice system has, Alexander argues, ‘immunized’ itself against claims of racism, and the book is most disturbing when it takes us into court.

But this is not where this ‘New Jim Crow’ stops; nor, indeed, even where it really begins. It is when the felon leaves prison that the extent of this system of control reveals himself, and where the parallels with Jim Crow become most disturbingly apparent.

The ex-felon will face legal discrimination in public housing and employment. His access to education and insurance will be, in many cases, limited or prevented. He may neither vote nor sit on a jury. His wages (in the unlikely case that he finds employment) may be garnished up to 100% to repay the costs of his imprisonment. He becomes part of a ‘felon underclass’ – a tranche of society that has been utterly marginalised, disenfranchised and dispossessed, under the pretext of ‘getting tough’ on crime.

The obvious difference between the old Jim Crow and this ‘New Jim Crow’ is that the former laws was openly racist, where the latter is officially and legally colourblind. You can’t discriminate against black people. But you can discriminate against ‘felons’; and the distinction between outright racism and a race-neutral ‘tough on drugs’ policy becomes merely one of terminology when almost every ‘drug-criminal’ is, due to the racialised design of the legislative and judicial system, black, and where blackness and criminality are held as mutually affirmative values.

Why is it worth looking at The New Jim Crow in the light of the riots?

Many reasons. First, because the response has been an excellent example of the dangers of ‘colourblindness’- the cloak of race-impartiality that makes ‘scum’ and its friends so popular has allowed media and politicians to shape a discriminatory narrative – to define and vilify a ‘feral’ underclass in society without censure.

Second, because the riots, like Michelle Alexander’s book, bring into focus the prejudices that silently underscore our approach to criminality. Her book is an elegant and devastating critique- a corrective to complacency, and a call to arms.

In America the book has become a sensation. Alexander is now a civil rights hero, ‘New Jim Crow’ a national synonym for systematic injustice that is heard across news and social media. Alexander places herself in a line of scholars and activists who have shown that the euphemisms of racial control (like ‘the War on Drugs’) remain, as ever, open to resistance.

The New Jim Crow

Michelle Alexander

Hardcover: 290 pages

THE NEW PRESS; 1 edition (12 Feb 2010)

Jonathan Jacobs is a writer and activist based in the UK.

5 Comments

adam

The politics of being: ‘Who Are We?’ by Gary Younge | Ceasefire Magazine

[…] control is entrenched in the US prison and criminal justice system is not, even though this idea is now virtually mainstream and would have strengthened Younge’s analysis of Obama’s weak role in combatting […]

junius

stupid shit

adam – I agree. It has to be up there with other significant works. If only it were to be printed in a slim volume with scholary apparatus and appendices, I would not hesitate in slipping it alongside my worn copies of Bakunin and Stirner. In certain writers – certain special writers – the urge to tell the truth, AS IT REALLY IS, can be a true inspiration.

Keep it up

Ian x

MISC/ACTIVIST /ACADEMIC/COMMUNITY « London Riot Archive

[…] Mag, Jonathan Jacobs: Paint them black: the riots and mass incarceration Ceasefire’s Jonathan Jacobs reviews Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim […]

An important and timely piece. There can be no doubt of the racial element of the riots, even when we consider the class elements, are of huge significance.