Widening the Lens: Revisiting Mandela Reflections

New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, July 18, 2014 14:30 - 0 Comments

In 2009, the UN General Assembly took the unanimous decision to launch Nelson Mandela International Day in recognition of Nelson Mandela’s birthday on 18 July. In marking it this year, I want to look at a recent documentary which is partly addressed to the generation Mandela was speaking to when he called upon it to take up the burden of leadership by saying that “it is in your hands now”.

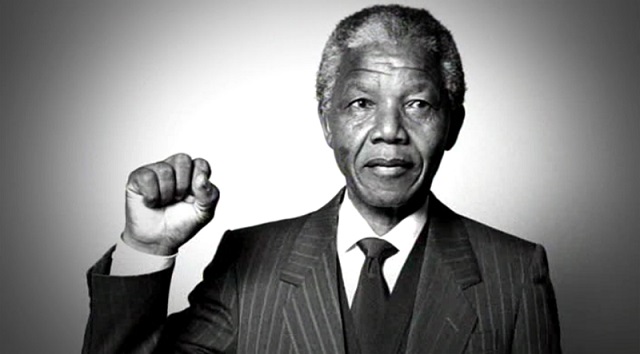

Although it is undoubtedly true that, as President Obama said in his “Remarks on the Death of Nelson Mandela”, that Mandela was a man who “took history in his hands and bent the arc of the moral universe towards justice”, Mandela was never happy with being treated in isolation from his comrades in the struggle nor in being classified as a saint: “I am not a saint, unless you think of a saint as a sinner who keeps on trying”. Despite this, many of the films and books about Mandela, as well as the countless number of tributes since his death, have persisted in the hagiographic vein he resisted.

The most challenging documentary made to date about Nelson Mandela, Mandela: the Myth and Me (2014; originally titled A Letter to Nelson Mandela), is by Khalo Matabane and is in keeping with Mandela’s farewell address to the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, in which he said that his legacy should be interrogated. Too many of the films made about Mandela fail to do this, as I have said, and, as Teresa Phelps has cautioned, there is the need to be wary of any template “that calls for a certain kind of story, a certain kind of process”, something which the TRC did not always manage to avoid for example, and “be brave enough to trust stories to be tools of disruption”. (Phelps 2004:128).

The form of the documentary is epistolary and is shaped around an imagined letter that Matabane is writing to Mandela. It was premiered in November, 2013 at the International Documentary Festival, Amsterdam. The structure of the film is constructed around a prologue followed by three sections: Freedom, Reconciliation, and Forgiveness, ending with an epilogue. The letter, which addresses a series of questions to Mandela, threads through the documentary and alternates with archival footage mixed with interviews of a number of people who speak from a range of perspectives, many of which are critical.

In the absence of Mandela, responses to these questions are put together in random form through the medium of the talking heads. Rather than following the conventional trajectory of most documentaries, the form is that of a fragmented patchwork or mosaic with no overarching narrative which connects the different components in any explicit sense, other than through the letter. It is not a work of iconoclasm as such but it does attempt to widen the lens on Mandela beyond the hagiographic and the dutiful. The film was made over two years, in the final months of Mandela’s life, and consists of interviews with those who knew him as well as some who did not but are asked to reflect on the implications of his release and efforts at forgiveness and reconciliation. In some respects, the focus of the film is not so much on Mandela but on conducting a critical meditation on the uses to which he has been put, and, to a certain extent, the uses he made of himself in terms of image-management.

Matabane was born in 1974 and, influenced by his grandmother, came to ‘worship’ Mandela as a hero even though it was forbidden to mention his name. The letter begins with the affectionate ‘Dear Tata (father)’ and repeats this each time he resumes the letter, either in voice-over or on camera. It is partly an autobiography, partly a tribute, as well as a series of questions to the figure who ‘captured my imagination’. Some of the extracts in the film are from Mandela’s own speeches, others focus on public figures like Colin Powell, Peter Hain, Albie Sachs, Wole Soyinka, the Dalai Lama, Ariel Dorfman and Henry Kissinger and Archbishop Tutu. There is a generational structure to these interviews as many of the ‘unknown’ subjects are peers of Matabane, and tend to be more personal and critical while the ‘known’ are mostly of an older generation, weighing their words in more formal fashion.

Taking Mandela’s words on his release literally, Matabane seeks to address not the prophet but the ‘humble servant of you, the people’ and his focus is not just on Mandela but on the state of South Africa since 1990 and in the present day, building a picture which is less illusory than so much of the Mandela ‘industry’. In this context, he explores issues of the burden of history and memory, what of the past should be forgotten and what remembered. As a child, he envisaged Mandela as a mythical figure, a character from a fairy tale and the letter is an attempt at dismantling this version and trying to understand whether he had to take on a new identity, become a different person, in order to transcend the past.

It is, by implication, not only Mandela that this is addressed to but also the filmmaker’s contemporaries as they seek to overcome the contradictions posed by the need for reconciliation, forgiveness and peace in the face of scars and continuities from the past. In the initial stages of the film, Matabane is constructing a profile of Mandela from brief sketches given by those who met him and it is a contradictory account – ‘the people’s man’, ‘cold as ice’, ‘with the non-violence principle in his face, his eyes’, ‘man with a strong temper that people didn’t want to cross’, and trivialised by his association with hollow celebrities – images are shown of Michael Jackson, the Spice Girls, Oprah Winfrey, and Prince Charles.

A sharp break with this profiling is made by Pumla Gqola, a feminist who changes the tone of the documentary through a critical analysis of the dominant Mandela narrative with what she perceives to be its narrow framework, arguing persuasively that there isn’t enough space for the revolutionary, for argument, for taking up arms, for land and real redress in that narrative, but only for ‘the man who doesn’t like suits’, ‘the teddy bear old man’. What she is articulating is the displacement of an earlier Mandela narrative (revolutionary, the armed struggle) in favour of an anodyne set of media-friendly images. It is a displacement which recurs throughout the film and forms one of its core items in the interrogation of the legacy, the contrast between the miracle worker in a country where there are no miracles, a country in which people fought for freedom and paid a huge price in a land stained with blood and are asked to forgive.

Footage of the 1961 ITN interview with Mandela, when he was ‘underground’, emphasises his shift from non-violence to the armed struggle, as does the Rivonia trial and the life sentence passed on the feared ‘revolutionary’. “Tata Mandela”, the letter resumes, “how do you feel about interacting with the very same people who once labelled you as a terrorist?”. This whole segment is not designed to undermine Mandela’s massive contribution to the ending of apartheid but to demystify it and open up spaces, to interrogate, not the man himself, but the mis/uses to which he has been put, to restore for a generation who were children or teenagers when he was released from jail the gaps in the narrative.

It is a struggle with ‘organised forgetting’, between history, memory and myth, addressed to his own generation but, in the context of archival images of protests, black funerals, and white violence, also seeking to recover the ‘lost generation’ which tackled the apartheid regime head on, and were killed or detained while Mandela was incarcerated. This, again, is not to demean Mandela, but to retrieve, document and register dimensions of the struggle and sacrifice cleansed from the ‘rainbow nation’ story. An interview with an activist of that generation, Zubeida Jaffer dramatically reinforces this argument as she tells of her imprisonment and the threat to kill her unborn child if she refused to inform on her comrades. Her situation is not necessarily representative but it illuminates the kind of choices faced by those in the struggle, the ‘foot soldiers’.

Matabane raises a series of hard questions as he returns to see the poverty in his own village and learns of the death of many of his peers. Whose freedom is it, he asks, “was the struggle for all, or for a few?” touching on issues dealt with by Patrick Bond in Elite Transition: From Apartheid to Neoliberalism in South Africa (2000) and Sampie Terreblanche in A History of Inequality in South Africa, 1652-2002 (2002), both of whom address problems of poverty, health, land scarcity, continuing racism and exploitation, as well as the links between white corporations and ANC leaders.

What the film also questions is the ANC’s commitment to market capitalism and why nationalisation of the banks and the mines, central to the Freedom Charter of 1955, and the demand for restitution had been abandoned. By using captions which spell out the realities of poverty, inadequate housing, and gross inequalities in wealth and education, Matabane brings up the kind of questions few dare to ask and backs these up with the testimony of a number of activists, or, in the case of Selina Williams, the sister of a woman who was blown up in a bomb blast. In the mortuary, she says she saw not her sister but ‘a broken human’, which causes her to reflect that South Africa was created by its people and not one individual’s greatness: “there were too many sacrifices and it was a unified struggle; we can’t give all the glory to one person”. This is a necessary corrective, not to Mandela, as he himself has always asserted this, but to the visual and print industry that has grown up around him. As Albie Sachs, an ANC leader blown up in 1988 in Lusaka, points out, the symbol of Mandela became more powerful than what he stood for.

Matabane fantasises about ‘the revolution we never had’, asking if is better “to accept a dirty compromise than go to war?” (this is asked over an image of an amputee on crutches, perhaps offering a visual answer to his own question). One of the main complaints of the non-establishment figures is that the price of peace was too high and that structural violence, degradation and re-traumatisation have occurred because of the failure to materially transform and transfer power. There is a debate running through the film between the ‘non-establishment’ and ‘establishment’ figures, even though they never engage with each other, or one another, explicitly, and people like Sachs, Dorfman, and Soyinka, who have experienced systemic violence and tyranny, all counsel against violence, perhaps because they have seen the scale of military power of oppressive regimes.

One of the most powerful segments of the whole film is that where the focus is on Charity Kondile, a woman whose refusal to forgive her son’s killers at the TRC epitomises the dilemma at the heart of the documentary. Initially, she refuses to meet Matabane but when she does agree she becomes the most powerful witness to the irresolvable enigma at the core of the interrogation. Kidnapped in Lesotho in 1981 and missing for nine years, her son was burnt to death by Dirk Coetzee and his accomplices. Coetzee finally confessed to her, and told in graphic details how they ate while watching his body burn for nine hours – “they acted like cannibals”, she says over images of transcripts of her TRC evidence. While others were being jailed for murder she could not see the fairness in forgiving them for their atrocities. She speaks philosophically about the need not to be rushed, articulating that forgiveness is a process with several stages which takes time and how important it is to acknowledge anger followed by forgiveness, eventually, but not forgetting.

In other words, there can be no shortcuts. This model of a deliberative procedure acts in exemplary fashion to point up what for many of Matabane’s interviewees has been a crucial problem since the release of Mandela, the seemingly obligatory ‘one size fits all’ model of reconciliation. For many, the whole question of reconciliation is too conflicted, too challenging to be fitted into a single template, and they do not wish to see it practised unconditionally but with a set of conditions linked to justice and equality.

In the final section of his letter, Matabane acknowledges that even after two years of making the documentary he does not understand Mandela but, seeking answers, clues in Mandela’s childhood village, uncovering traces and metaphorical footprints, he comes to realise that the meaning of the whole Mandela phenomenon cannot be reduced to simplistic or facile stories of greatness or heroism but is inextricably tied up with the antinomies and contradictions of South African history, an unresolved and complex, ongoing history which ‘weighs on his shoulders’ and those of his generation that came of age when apartheid was on its way out and a new South Africa was being born.

It is this new South Africa which he seeks to uncover in his final interview with two men and a woman, born in the 1990s. Almost everything they say is positive, if materialistic, but also checked by the ways in which the mantras they echo (‘rainbow nation’; ‘Mandela gave us freedom’) are partly undercut by the contradictions they are aware of, poverty and unemployment, for example. One clear position emerges and it is that their version is a bourgeois one – “we want to get to the top, to be multimillionaires’ – or a total fantasy, which suggests, along the lines of the comment on black elites earlier that where race was the primary marker of difference under apartheid, class may well be the factor dividing the new South Africa.

According to de Certeau, “Stories map out a space which would otherwise not exist” (quoted in Humphrey, 2005: 17). One of the primary cultural tasks of any post-conflict recovery is this mapping out of spaces which had not previously existed or which had been obliterated. Apartheid disempowered, immobilised, silenced and isolated its ‘others’. Legal, political and sensory deprivation combined to dominate and abuse, to remove the possibilities of language and communication, of the power to story. One of the tasks of reconstruction after such terror is to reconstitute society in terms of mutuality, not as some kind of abstract or woolly process but as a form of political action itself.

In this context, forgiveness is not simply a personal act but is, as Arendt has argued, inherently political, in that it seeks to re-associate the individual with their belonging, to make possible a return to the presence of others. As Aletta Norval has said, apartheid functioned “as a signifier of closure” (Norval, 1998: 259). There is some danger, as has been indicated, that a similar closure might have been produced by the dominant mythologies of Mandela. Following his death, there is a need for narratives which extend, defamiliarise and subvert existing liberal-rationalist paradigms – multi-dimensional, challenging, and radical explorations of the relationship between power, discourse and the symbolic. Stories do not simply describe or relate but are also actually constitutive of something new.

References

Humphrey, M., 2002, The Politics of Atrocity and Reconciliation: From Terror to Trauma, Routledge, London.

Norval, A., 1996, Deconstructing Apartheid Discourse, Verso, London

Phelps, T. G., 2004, Shattered Voices: Language, Violence, and the Work of Truth Commissions, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

Leave a Reply