Western Sahara: “These camps will never be our home, we want to return to our homeland.” Special Report

New in Ceasefire, Special Reports - Posted on Saturday, January 4, 2014 14:38 - 16 Comments

Woman crosses the street in a deserted part of La’ayoune in occupied Western Sahara.

La’ayoune, Western Sahara

In early December 2013, I arrived in La’ayoune, the capital of occupied Western Sahara. The issues that frame the Sahrawi people’s ongoing struggle for independence had led me to the cities of Smara and Dakhla, in Western Sahara, as well the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria.

The legal status of the Western Sahara and the question of sovereignty remain unresolved. The territory is contested between Morocco and the Polisario Front. It is considered a non-self governed occupied territory by the United Nations. In Morocco, meanwhile, there is no debate as to whom the region belongs to; “it is Morocco’s land, it has always been part of our country” my taxi driver tells me quite confidently.

Speaking about the issue over dinner raised a few eyebrows too. As for those directly suffering, the Sahrawi people, the outlook for the ongoing colonisation of their land can be best described as a political stalemate.

The Saharawi people want to be granted the dignity of being met on their own terms, the recognition that they are equal to others in the land and a place they can call home.

As you travel through La’ayoune you will probably notice a lot of well polished UN vehicles and convoys guarded by security personnel. Many of the Sahrawi people I spoke to have described the situation as ‘nothing happens here, nobody comes or goes anymore’. Perhaps that is because visits by UN members usually involve spending days in a luxurious hotel in the heart of La’ayoune and partaking in tourist-like activities (visiting beaches and camel riding). As you head towards the border you will notice there are no UN vehicles heading in that direction.

My translator continuously provided with background facts as we passed milestones on our journey; for instance tales of Sahrawi women gone missing, kidnapped from their children for protesting.

I soon started to realise the reaction my reporting and presence could elicit from the Moroccan authorities. My camera holds two memory cards. The first one, which always remained inside the camera, had a variety of images of Sahrawi food and tea making that I could show at certain checkpoints.

One night, I was visited by a policeman and driven to the nearest checkpoint to be detained for some time whilst they noted down my “information”. He asked to look at what I had been doing in the Sahara, and my “official” memory card holding picturesque images came in handy. With silent piercing looks he sent me away. His parting instruction: ‘next time, let us know where you are going’.

As any photojournalist knows, keeping the authorities posted on my every move was not only incredibly time-consuming but restrains one’s abilities to report freely, so I just disappeared one night to spend time among Sahrawi bedouins and document the hardships of their daily life in the region.

In Layyoune, an outbuilding catering for orphaned children drew my attention, babies under the age of 2 sleep in rusty cots and are tied with ropes. There were looks of despair as I left the building, eyes spoke words ‘take me’ and ‘help us’. I witnessed the slow death of a baby girl who had been suffering immensely, nobody spoke of what happened to her, just that she had been ill.

When a photojournalist arrives in such a situation they assume that they can somehow steal the pain of these people. One continually suffers the shame of the memory and the helplessness. You have to sleep with the images embedded into your mind. Still, the responsibility must be faced and acknowledged. By picturing such harsh realities one must vow that something must come of out the time stolen from these people’s lives.

My journey took me further towards the Algerian border. Our rusty vehicle passed through minefields, and as sunrise approached you can see the white canisters littering the side of the road for hundreds of miles.

Tindouf, Algeria

We couldn’t cross the border to get into the Tindouf Refugee Camp, in neighbouring Algeria, by land so ended up travelling there by air via Morocco. The limited opportunities for self-reliance in the harsh desert environment have forced the refugees to rely on international humanitarian assistance for their survival. Most affairs and camp life organisation is run by the refugees themselves, with little outside interference.

There is a lack of clean water, canvas tents propped up in endless rows, and harsh sandstorm conditions that are almost insufferable especially for many children. Your throat seems always parched because of the dry conditions, the eyes constantly under assault by the sandy gusts.

A call to justice

The plight of the Sahrawi people, whether in the refugee camps in Algeria or in the occupied Western Sahara, and the images you see before you must be a call to justice; pressure must be placed on the UN in ending the deadlock in talks to create the prospects of a peaceful resolution for the Sahrawi people.

Not long after I left the region, the President of the Polisario, the Movement for the Liberation of the Western Sahara said the people will arm themselves against Morocco if the UN does not organise the long promised referendum on self-determination.

An oppressed people who have mostly bottled all their frustrations for over 38 years, with no land or country, and who have kept their resistance largely peaceful, will eventually resort to armed struggle, as they are well within their rights to do.

Despite it being one of the most inhospitable places on Earth, they are making up a powerful force in their daily struggle and women are being empowered to take a lead in making that change. As one Sahrawi woman in the Tindouf refugee camp told me “Don’t try to confine me to some tiny part of the world you can give to fit me in. These camps will never be our home, we want to return to our homeland”.

There is a sandstorm brewing in the Western Sahara and it is not the one created by the Saharan winds, but within the souls of its people crying out for a place to call home.

A man visits his baby boy in La’ayoune.

A mother and daughter sit discussing life in Layyoune.

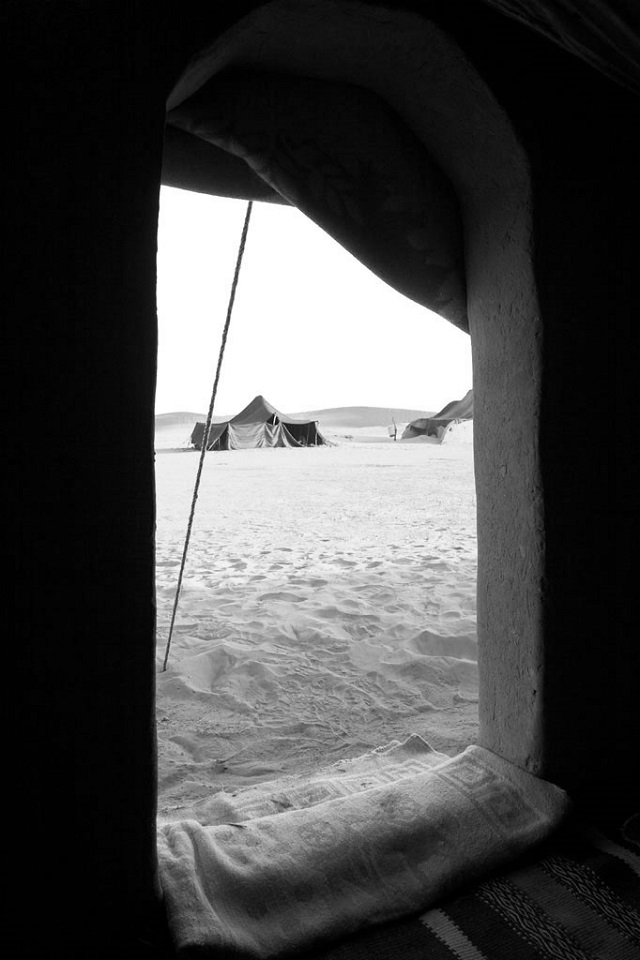

A series of tents where I was housed near La’ayoune.

Child swings from side to side in a metal-framed cot in a La’ayoune orphanage.

Child tied to a cot (La’ayoune).

A girl in La’ayoune on her way to get bread.

Girl plays with donated soft toys that arrived during my visit (La’ayoune).

Man carries his entire belongings with him (Western Sahara).

Child sandal lays buried in the sand (Western Sahara).

Man tends to his camels (Western Sahara).

The child on the left sleeps. The one on the right had passed away moments earlier (La’ayoune).

The one child who was not clapping along to songs, gave me a unforgettable look (La’ayoune).

UN vehicles lined up at the beach in La’ayoune.

16 Comments

Adam

Eugene Egan

Powerful photography illustrating the gritty and harsh realism of their lives.

Most of the pictures are not Saharawis rather they are from Atlas “Morocco” the writer got her information wrong or bad source. and the article completely wrong in fact far from the truth…maybe she should review the international resolutions.

I thought I was reading “hesspress” not a UK magazine. I’m just curious about your source; or maybe you just repeated the Moroccan propaganda !!! what a poor journalism ..

please refrence to the UN and other then you government..

Thanks Sahra Libre, the article says the Western Sahara is occupied territory and the Sahrawi people are fighting Moroccan colonialism. Are you saying this is Moroccan propaganda?

Best

H

Sabiha Mahmoud

La’ayoune is half morrocan occupied and other side of it is Polisario Front all the way upto the Berm sandy wall. Many from camps have travelled and lived in La’ayoune, they are no less Saharawi than anyone else. My flight information and contacts especially in Polisario La’ayoune can confirm that these images were taken there. In regards to Tindouf after unsuccesful attempt by road a plane journey was taken perhaps I didn’t write this in detail. But my full solidarity is with the Saharawi people for their liberation from Morocco (and no I haven’t been paid by any such person to report this). As I have said I am a photojournalist not a writer.

If any offence was caused then I sincerely apologise but my story is nothing but sympathy with the cause of the oppressed.

Salma

thank you very much Sabiha for your solidarity with the Saharawi people,Western Sahara issue suffers from the negligence of the media.as a Saharawi i appreciate your efforts. your article can make the people familiar with this forgotten conflict

Allison

The article is very confusing – the author traveled by plane or truck? The article states: “My journey took me further towards Algeria, right up to the border, into the Tindouf Refugee Camp. Our rusty vehicle passed through minefields, and as sunrise approached you can see the white canisters littering the side of the road for hundreds of miles.” So this is true or untrue?

Of course, there are vast differences in the situation of Sahrawi living in the Moroccan administrated territories versus the SADR administrated camps in Tindouf (further complicated by the presence of two “La’ayounes.” Is it possible to also clarify the encounter with the “policeman?” Where did this occur? There is mention of the “Moroccan authorities” – I would be astounded to learn a Moroccan policeman would interrogate a journalist inside the Tindouf camps, in internationally-recognized Algerian territory. Any clarification?

Thanks.

Thanks Allison, we’ve added some clarifications in the text to help resolve some of the confusion you mention. The author travelled to Algeria (via) Morocco by air as the land route was not accessible.

Best

H

Malainin Lakhal

Good work Sabiha. I am myself a journalist from Western Sahara, and I know how difficult and challenging it is to work on the issue of Western Sahara, especially for a foreign journalist in the occupied cities.. I think that you should not be intimidated by criticism or any bad comment here, most of them are just opinions, and everyone has got the right to his or her opinion, but when it comes to facts, they must be respected. And that’s what you did. Also, talking from a first hand experience is unlike talking from behind a computer for someone who never visited the region and yet talks about it. It is also true that it is very confusing for someone who don’t know all facts of the political, social, economical and legal reality in Western sahara.. But could you write about all this in this space? Congratulations

[…] via Western Sahara: “These camps will never be our home, we want to return to our homeland.” | Cease…. […]

Saowani

Hey Sabiha, well done on this powerful piece.

As for some of the comments on this article, I’m not sure why Sabiha’s transport details are being put under scrutiny here. When reflecting on this piece about the Sharawi people, I wonder why those trivial details even matter. But it’s a great way from deflecting from the topic of the article, right? On top of that, the accusations about these photos being forged, and that she wasn’t really in Western Sahara, are absurd. How insulting it is to reduce someone’s time, energy and work to this. You might as well claim the same for any set of photos that are featured online. Why is Sabiha’s article a special case to be singled out?

Perhaps Sabiha could have presented the facts better. But this article is a reflection of what she experienced there, on the ground. Which is better than her having a claim to the facts of the situation. She’s being honest here.

I’ve never hear of this matter, until it was brought up by Sabiha’s work which illustrates the impact it’s having. Hopefully she can contribute more work on the topic, which I’m sure many of us would welcome in the future.

Luke de Noronha

Brilliant article, beautiful pictures. Thank you.

Allison

To address my comments – I am a researcher who works on the Western Sahara issue. Even the “trivial” details are incredibly important. Comments are not meant to discredit the article but to find out details, to clarify and make it stronger. Critical engagement is absolutely essential, particularly regarding such a sensitive and controversial issue that is so frustratingly conflated with propaganda. I urge any reader (to this or any other article on the topic) to engage with authors and to press for the most complete and detailed accounts of movements and interactions in either the occupied territories or in the SADR controlled camps.

Walter Benjamin: Critique of the State (and resistance) | ΕΝΙΑΙΟ ΜΕΤΩΠΟ ΠΑΙΔΕΙΑΣ

[…] Special Report | Western Sahara: “These camps will never be our home, we want to return to our hom… Saturday, January 4, 2014 14:38 – 14 Comments […]

GPJA #491 (2 of 2): International news & analysis – 23/2/14 | GPJA's Blog

[…] “These camps will never be our home, we want to return to our homeland.” https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/western-sahara-these-camps-home-return-homeland/ […]

Beautiful piece and amazing pictures, give a real insight into the situation there.