An Oddly British Jubilee Weekend Blog

Ceasefire Bites, Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, June 5, 2012 15:43 - 3 Comments

Like most people in Britain, the thing that made me most happy about the Jubilee weekend was the four-day weekend. My partner and I decided that the best way to celebrate this extended holiday would be to leave the centre of power for a night, and find somewhere serene and quiet away from roaring crowds of wannabe medieval serfs, pleading for the honour to toil on the land of their divine overlord.

We arrived in Worthing (just outside Brighton), at a pleasant enough sounding hotel, and decided to drop off our bags and go for a walk around the local shops and seafront. Unlike London, the weather was sunny and warm, but as in London, union jacks were still tastefully incorporated into every shop window, waterproof anorak, straw hat, dog-collar and child’s facepaint design. Stopping for a (very English) cup of tea in a café, we sat outside, and were eventually asked by an elderly local, “Where are you from?” (Hari Kondabolu translation: ‘Why are you not white?’). Replying, almost wearily, as we knew it wasn’t the answer she was looking for, we said “London”. This did not go down well, as, the women observed, my “afro hair” meant that I could not possibly be from London, so she took an informed guess with “Nigeria”. We’ve all got to take a day off, so instead of descending into the history which explains that:

a) I may well be from Nigeria, but my family grew up in St. Lucia due to the legacies of British and French colonialism and enslavement.

b) It is possible to be from London and have an afro, as the ‘afro’ generation before me were invited there by the Queen of England as citizens of the commonwealth.

c) I shouldn’t have to answer these questions given this historical legacies of a) and b)

…. I just told her I was from the Caribbean.

Upon returning back to our hotel, we found that our room was not yet ready, but were invited to take a seat in the ‘Colonial Conservatory’. Yes.

The name Colonial Conservatory was actually very clever, because not only was it a colonial-themed conservatory – it was also a way of actually conserving colonialism.

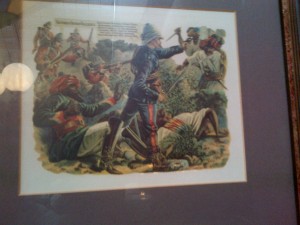

The first pictures on the walls were of smug looking colonial officers. It could be worse, we thought. And we were right, because that is what it got. Two of the most prominent pictures which stood out for me, were of British soldiers defeating Indians, holding pistols to their heads, or holding swords to their necks. I simultaneously felt sickened, horrified, angry and bemused. The bemusement was partly due to finding it difficult to understand how such torture and suffering could be celebrated so casually, but mainly because of what I saw next.

On a pillar, in the same room was a poster for a club night which was taking place in the basement below the colonial conservatory.

It was a Dub night. A Dub Night called Dub Hustlers. A Dub night, called Dub Hustlers, with a Jamaican flag on it, and a picture of Bob Marley. A Dub night, called Dub Hustlers, with a Jamaican flag, picture of Bob Marley, taking place IN THE BASEMENT UNDERNEATH THE COLONIAL CONSERVATORY.

We walked outside, and a local (and therefore white) man in his late 50s, balding, with light brown ‘dreadlocks’ wearing a yellow, black and green vest was attaching a giant Jamaican flag to the side of the colonial conservatory, just above the entrance to the basement. He looked pleased to see us, and even more pleased when we said we might pop in for a drink later in the evening.

We found a very nice Turkish restaurant on the seafront imaginatively titled ‘Istambul’ (my partner noted that the more ethnically homogenous an area gets, the more generic the title of non-British restaurants become) and then headed back, with morbid fascination, to our hotel.

First, hats off to the organisers. The soundsystem wasn’t bad at all, and in fact (as it should) shook the whole building. They also had a fantastic turnout, with everyone in the venue not only dancing, but seeming to know the words (or at least sounds) of the songs being played. The playlist wasn’t anything groundbreaking, but I’ll cut them some slack seeing as they are below a colonial conservatory in Worthing. Then of course, as I should’ve guessed, the inevitable happened. From the edge of the dancefloor where we stood, we looked through the crowd, as a local man, with a union jack painted on his face, took the microphone, and started ‘rapping’.

Needless to say, we didn’t stay for more than one drink. Feeling less like tourists and more like Louis Theroux, we slipped away from the culturally eclectic crowd, to the relative safety/normality of our room.

The next morning, coming down for breakfast, which was served in the colonial conservatory (I would’ve boycotted if we hadn’t already paid for it, promise), we saw a another Black couple. Not only did we see a Black couple, but they seemed to just be eating happily, not seeming to notice the depictions of torment and bloodshed around them. They didn’t even look over and give the ‘nod’ which I’d got from Black tourists in the past when travelling around Eastern Europe… or the Lake District. Finding a corner which shielded our gaze from the portraits of colonial officers, we ate, and left for a town 20 minutes away where we knew we’d be safe. A land of liberals, environmentalists, hash smokers and peace activists . A land of inclusivity, culture and royal-skeptics. Thank god we escaped alive, and made it across the border for a less dangerous day trip before heading back to London.

In this new world of intellectual tolerance, we pondered the cultural patterns emerging from the postcolonial legacies we observed in Worthing. The screaming metaphors and silent reactions. Maybe I’ll use the experience to write a theoretical essay. Or perhaps I’ll just save it to tell my grandkids in 40 years, as we walk past another grime rave on the Isle of Man.

3 Comments

Ghazi

Adam Elliott-Cooper

Hi Ghazi

I guess I found the pictures of South Asians being killed by British colonialists problematic because it re-enforces the normalisation of Black/Brown suffering and death (similar to the idea that certain parts of the global south are in a perpetual state of suffering and death). It also glorified historical atrocities which I think need to be addressed through reparations (I’m talking historical education and fair economic policies rather than cash handouts of course).

Being asked where I’m from isn’t necessarily offensive, but, as the translation indicates, what I was really being asked is ‘why are you not white’? The reason those kinds of questions are asked, is precisely down to the existence of both a) and b) as well as c).

I don’t see it as my responsibility to inform white people about the diversity of Britain.

I spend a lot of time writing, education and campaigning around issues of race, and I meet ill informed parts of society on a daily basis. The ones I tend to concentrate my energy on are the centres of power – government, education system, financial/corporate oligarchy, media, police etc. rather than pensioners in Worthing (plus, I was careful to note that I was determined to take a day off!)

Bob

Great article Adam, I’m always shocked at how embedded racism is in our society (naively so, perhaps). A parallel can be drawn with the ridiculous attitude some people have towards rape: that the burden of responsibility lies with the victim and not the oppressor. No brown people should not feel the need to explain and justify their existence to deter continual oppression. Yes white people should start by recognising and condemning the brutality of their history (and present).

I could agree that such paintings can be offensive to some, but I would not personally pay that much attention to them. However, I don’t see why would an Afro man being asked where’s he from can be offending? He should have actually told them a) b) and c) if there was a ‘c’! It’s actually part of his responsibility to bring it to their attention and enlighten them about the diversity of Britain. Instead he literally ‘escaped’ from answering and blamed it on other factors which are really beyond his control in my opinion.

I could go on forever, but dwelling over past demeanor is actually one of the reasons why the writer is still being asked where he is from!

He had an opportunity in meeting an ill-informed part of the society to explain to them what makes him British and why the paintings are offending, and he rather decided to escape to another part of the country!