And Still We Rise: On the Violence of Marketisation in Higher Education Beautiful Transgressions

Beautiful Transgressions, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, March 1, 2012 8:53 - 11 Comments

By Sara Motta

London Occupy, having just being evicted from the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral, have asserted their continued resistance to the violent logics of austerity, declaring that ‘This morning, the City of London Corporation and St Paul’s Cathedral have dismantled a camp and displaced a small community, but they will not derail a movement’.

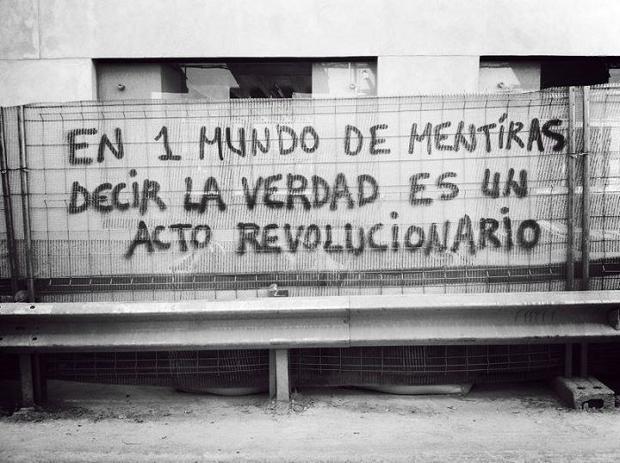

The violence of marketised austerity attempts to eradicate spaces and times of possibility and, with this, criminalise and erase forms of being, acting and thinking outside of commodified logics. Yet practices of solidarity, democracy and community appear in the cracks and margins refusing to be eradicated from history.

Such violences are also being enacted throughout the University sector. In bearing witness to a part of this story from the perspective of an academic worker I hope to make visible some of the cruel realities of marketised austerity. I do so as a way of rupturing attempts at the eradication of being ‘other’ and in solidarity with all those attempting to create spaces and times against and beyond market logics.

‘We are a business now. We have to do our marketing intelligence and make a business case, see if it will work to students’ expectations for a high quality consumer experience. We have to bid for funds, we have to compete, we have to make tough decisions, we have to survive; we have to bring in money. This is the reality now. This is the new context. We have to be realistic and feasible and lucrative. We are a business now.’

How many times over the last few months, in different meetings and spaces in the academy, have I heard this discourse? There isn’t even the pretence that we are in a public educational space of inclusion which creates knowledge, that is meaningful for communities, embedded in society, open and democratic, facilitates the flourishing of ideas which are tools for social transformation and social justice, and which enables us to dream and turn the impossible into possibility.

The shift is powerful. It is an attempt at the final closure of the possibility of an education project, practice and subjects outside of marketised logics.

Such a discourse enacts a symbolic violence* of erasure of the possibility of thinking, acting and feeling outside of these dehumanising, individualising and impoverishing logics of market value. It turns all of us -from the liberal humanist to the revolutionary educator – into the unspeakable ‘others’ whose dreams, objectives and desires for a public, inclusive and critical education become incommunicable and non-sensical.

To speak in another logic and language is misnamed and misrepresented as “outdated”, “unrealistic”, not related to the “realities” of student desires, “disloyal” and “disruptive”. It is not just the naming that excludes and silences, it is the looks of incomprehension, the crossing of the arms, the looking at the watch, the exasperation and the moving on in the meeting. The possibility to even speak differently from this logic slips through the quicksands of marketisation.

The closure of political imaginaries and social practices spoken through those words are enacted upon the hearts, minds and bodies of the subjects who make up the academy. This is the ontological violence of non-being which silences possibilities of being, thinking and practicing otherwise.

The violence of non-being is constituted through multiple micro-practices of bureaucratisation and professionalisation. Through these practices, university educators are produced as particular disciplined subjects enacting particular performances of self with emotional repertoires and embodied enactments. The ideal type neoliberal subject is grounded in individualisation, infinite flexibility, precarious commitments, orientated toward survivalist competition and personally profitable exchanges.

This produces a space of hierarchy, competition and individualism through the eradication of spaces of solidarity, care and community. Some subjects and forms of behaving, feeling and embodying space are empowered and legitimised. Whilst others are delimited, disciplined and subjected to the dominant logics, allowing some to judge and others to be judged.

Imposed standards of excellence and quality are those to which the ideal subject is produced against and through. Her research, teaching and impact are ranked, categorised and evaluated in terms of their ability to bring in money by publishing in top-ranked publishing housing which produce hardbacks that cost £80 a copy or high ranking journals targeted at the few, as well as to maintain students numbers (to bring in money) and create relationships with non-academic users (the most valued of which are with the private sector and political elites).

Such standards push us towards the development of problem-solving theory which accepts the status quo, as opposed to critical theory which disrupts and denaturalises the market economy. It pushes towards meritocracy and populism in teaching and instrumental and elitist relationships with society.

If we do not perform to these standards we face judgements which are demoralising and shaming. If we do not perform to these standards it is becoming increasingly clear that many of us will face either being moved to the bottom of the pile in terms of workload, working conditions and precarity or losing our jobs.

The violences of marketisation are intensely embodied through the production of self-disciplining subjects articulated through abrasive dynamics of power against self and other. As Michalinos Zembylas has observed we must ‘regulate and control not only our overt habits and morals, but [our] inner emotions, wishes and anxieties’.

Under these circumstances subjects of the University may tend to discipline themselves by not questioning accepted beliefs and ways of acting but simply follow them in order to avoid marginalization. Such processes disconnect us from ourselves, and from joy, pleasure, meaning and creativity. They disconnect us from the very sources of knowledge from which we might derive our truths to speak against the dehumanising logics of market colonisation of being.

As Audre Lourde, Caribbean-American writer, poet and activist exposes so forcefully “This results in disaffection from most of what we do- the power of this system – excluding human need and physic needs, robs our work of its erotic value and power, its appeal and fulfilment, such a system reduces work to a travesty of necessities, or oblivion to ourselves or what we love and this is tantamount to blinding a painter and then telling her to improve her work, to enjoy the act of paining, it is not only next to impossible but it is also profoundly cruel”.

Yet as Maya Angelou reminds us

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

It is as the non-beings of marketisation that we speak to rupture the naturalness and normalcy of such an organisation of education to expose its faultiness and contradictions. In affirmation of Michelle Rowley, our critique “rejects and rebels against the acts of misnaming and misshaping [as a means to] produce a different set of parameters for what makes us minority subjects”.

Such a critique is enacted through rupture, disruption and transgression that reconstitute us as subjects on the historical stage, in the moments of meetings, in the spaces of classrooms, in the cracks of corridors, forcing our way up from the margins of marketisation. Yet our critique must also develop strategies for care of the self from the logics of isolation, silencing and de-legitimisation based in an ethic of love and recognition.

To rupture, disrupt and transgress takes the courage to embrace being the othered, the marginal and the outsider. This does not mean the marginalised should look for acceptance into the dominant frame. Rather as JanMohamed and Lloyd have suggested, it involves “the… attempt to negate the prior negation of itself” whereby individuals are reduced to a generic ‘status’ of being other, inferior, marginal. Such a political practice, within these conditions, is one of the most fundamental forms of affirmation. It enables the transformation of our scream of outrage into a dignified and powerful exercise of our voice.

To rupture, as the critical theorist and educator Sarah Amsler argues, the dis-utopia of marketised education, we can bring joy, laughter and play into our everyday practices. The work of the Yes Men is a good example from which we can potentially think through individual and collective strategies. They pose as top executives and convince organisers to allow them into business conferences. Once inside, they parody their corporate targets to wake up their audiences to the danger of letting greed run our world.

How might we parody the performances of the university conferences to which top business executives are invited? Of the training sessions in which we are taught how to be good disciplined professionals? Of the performance reviews at which are work is evaluated by imposed standards? The possibilities are endless.

Undoubtedly embracing and speaking from our otherness and marginality places critical academics in a very vulnerable and risky situation. Such practices will most likely not result in academic accolades from peers or acceptance and praise from managers. Yet, by daring to speak the unspeakable we transgress and liberate ourselves, however momentarily, from the individualised, commodified and hyper competitive performance of the university academic.

Humanising the educational space and experience challenges the taken-for-granted. It fosters the destabilising of the effects of power in our subjectivities, creating hybrid openings of possibility for imagining and being otherwise. These are the transgressive potentials of this practice.

However, rejection, derision, self-doubt, de-legitimisation and fear are also likely outcomes. Learning to embrace a desire to ‘always be’ other and marginal takes courage. Developing courage involves educating our fear collectively so that it can become a productive element of the on-going process of moving beyond ourselves and challenging marketised logics in the University.

Here an ethic of love through which we act with care towards our colleagues and with recognition of the painful complexities of our situations is a way to rebuild dialogue and connections from where we are. As critical educator and theorist Paolo Freire argued, “As individuals or as peoples, by fighting for the restoration of [our] humanity [we] will be attempting the restoration of true generosity. And this fight, because of the purpose given it, will actually constitute an act of love.”

Or as Bell Hooks, author, feminist, and social activist warns, “without an ethic of love shaping the direction of our political vision and our radical aspiration, we are often seduced, in one way or another, into continued allegiance to systems of domination”. The loving eye is a critical eye in that it creates the conditions for acts of kindness and solidarity through which we can re-build collectivity and political agency.

We cannot pretend there is not fear, nor underestimate the conditions of closure which produce this fear. Rather we can be voices who attempt to transform such emotions and anxieties into productive moments of courage. We can only do this by speaking our truth. Like this, “the more you recognise your fear as a consequence of your attempt to practice your dream, the more you learn how to put into practice your dream”.

Such practices of rupture when combined with an ethic of love create a radical disturbance of both ‘self’ and ‘other’ which may lead, as Claudio Moreira suggests, “to unanticipated, maybe even unspeakable, transgressions”.

Appearing as ethical and political actors from the margins of university marketisation, we rebel against the violence of non-being. We rebel against the violent logics of austerity which attempt to eradicate the possibility of radical education. We rebel by developing educational practices, ideas and relationships beyond commodification.

[* Franz Fanon and Simone De Beauvoir develop this concept in relation to the colonial experience and the experience of women. A beautiful analysis developing this concept, which helped shape this piece, Jumpstarting the Decolonial Engine: Symbolic Violence from Fanon to Chavez by George Ciccariello-Maher]

11 Comments

Greg Wild

Me

Was clearing the camp an example of trying to ‘criminalise and erase forms of being’, or was it simply clearing an unsightly shanty town, to which the majority of the capital were at best indifferent, from the forecourt of a World Heritage site and among the finest examples of Baroque architecture to be found anywhere?

Andy

@ “Me” (does that stand for Mail Enthusiast?):

Was posting that comment an example of expressing your opinion, or simply an exercise in the very practices of demonisation, judgement, ranking, silencing and fabrication of ‘common sense’ which Sara exposed in her excellent article?

What about how it dirties this medieval Christian heritage site to be turned into a commercial capitalist concern run for profit, and to be associated with a regime of ‘usury’ and violent police atrocities counterposed to Jesus’s teachings? What about the damage caused to historic sites and SSSI’s by capitalist development projects like the Newbury Bypass, the Nine Ladies quarry and the tourist-oriented road-building at Stonehenge? What about the hundreds if not thousands of listed buildings being allowed to rot away because the state and the owners won’t pay for their upkeep? What about the JB Spray factory in Nottingham for instance, a beautiful old factory and listed building which, prior to being squatted by activists, was in a ramshackle state, being left to fall down so someone could build student housing on the site?

What about the way the heritage of our own movements – the Hacienda in Manchester, Ungdomshuset in Copenhagen, the ephemera of the Occupy movement itself – are being wantonly destroyed by capitalism?

What about the looting of Iraq’s museums – carried out by allies of the imperialist invaders, and enabled by people like you, whose “Mussolini made the trains run on time” attitude was directed against the courageous protesters who tried to stop that dreadful war?

And, why is it that when people like you see a rare piece offering an alternative point of view, you feel you have to show up and spray around the same flak that your own media are offering on a 24-7 basis? Why are you so determined not to allow any alternative viewpoint to exist unmolested? Why do you feel so threatened by the possibility that your ‘common sense’ might be wrong?

Also, you lucky person, there’s a book about you here: http://www.listenlittleman.com/ please go read it 🙂

Andy

@ Greg, “is the market the problem, or is it the vested interests which rig that market in their favour?”

Interesting question regarding the role of superprofit nexuses as opposed to markets strictly speaking in contemporary capitalism. A lot of people working on the topic of the enclosure of “intellectual property” suggest that IP is now one of the major superprofit nexuses whereby the global elite keep profits within the core and out of the South. Obviously universities are closely connected to this move – and if this is the situation, then free/alternative universities providing education at no cost / a fraction of the cost could be a very effective counter-strategy.

The issue with journals has additional complexities: academics don’t get paid a penny for publishing in journals, on the whole they publish in journals for 2 reasons: 1) to get read by the widest audience possible and 2) to get recognised as a high-level researcher in university appointment and promotion systems. Not wanting to over-plug my own column 😉 but this is classic “sign-value” as discussed by Baudrillard: academics publish with journals mainly for the social status this confers, or for use-values dependent on such status. Now, status is, of course, a quasi-monopoly property which it is hard to break – hence why free online journals haven’t successfully broken the monopoly regime yet. It’s also kinda arbitrary, in that it only exists because people think it exists – the top journals aren’t necessarily “really” the best in terms of content, just the most recognised. The alternative is there to go and read stuff online, but there’s systematic reasons why people will prefer to stick to “reliable” journals (major ones being: there’s just too much stuff online and its reliability isn’t generally guaranteed; and the newer free-online journals tend to be low-status because they’re new). The journal system is being subverted all over the place however, with a great many journal articles being available free online, either in their full version or an earlier but very similar version. These pop up on academics’ home pages, university websites, even government departments – i.e. the very places one would expect the interest in IP to be strongest. What’s strange is that this kind of ‘self/peer-piracy’ is mainly perpetrated in the more ‘policy-relevant’ sectors – someone writes something on fighting global terrorism and one can near guarantee that some state or parastate body will stick it on their website. It’s the most interesting stuff, in areas such as critical theory, which seems to be journal-only!

Also quick mentions here of Aaaaarg, Marxists.org, The Anarchist Library, The Gutenberg Project, Libcom Library and the sadly deceased Library.nu.

E.Z.

As a marketing professional working for a Higher Education institution in the UK, this article adds to my already growing concern about what my work is contributing to, i.e. not just the marketisation of Higher Education but the marketisation of our society in general, an overwhelming tide to resist (yet to be resisted).

However, in the spirit of the article’s call for fearlessly being ‘other’, I’d like to offer my view that being business-like should not necessarily be considered a wrong thing to do for Higher Education institutions; there’s nothing necessarily wrong in gathering market intelligence, being competitive, taking demand into account and demonstrating the contributions to the advancement of culture and science and the impact of research to raise institutional profile; there should be nothing wrong in trying to improve performance, make a more efficient use of resources and serve the wider interests of society, not individuals’. Yet, I feel there is a certain tendency to discount such business-like activity as plainly evil.

Business-like does not need to be wrong if the overarching aim of higher education, i.e. to be in service of society, is kept intact; if long-term outcomes, sustainability and social responsibility, become essential aspects of the bottom line.

Andy

@ EZ – aren’t we assuming that people are bourgeois / RCT individuals in assuming that their needs or desires can be theorised in terms of demand, competitiveness, impact etc?

I agree that we should be seeking relevance (though not exclusively!) but I’m not sure that current marketing practices give us real relevance. I think there is often a vast gap between a direct human connection and a connection mediated by aggregate figures and market values. The people who have “need but not demand” don’t count, and needs get distorted by being turned into operational goals. It’s like (early) Marx said about the commodity-form, that it comes between people and their capabilities, or between each of us and everyone else. It stops us having really human relations because it means we only do things for others if there’s a personal gain.

To take an example: Hallward library has been closed-off to the general public for years now. Obviously this is denying scholarship to the community. It is reducing the university’s relevance. But this reduced relevance is non-quantifiable. It affects people who aren’t counted in the figures. From a managerial point of view, gating the library was a good move because it reduced theft and allowed data mining on library use. It produced figures which could be used to generate value.

In many ways, inclusive relevance and efficiency are counterposed goals. Efficiency requires trimming off anything which doesn’t contribute to profits – thus achieving relevance to the dominant system at the expense of losing relevance to everything and everyone else.

Arthur P. Arthur

Have you met Rod Carr, a university head leading the charge in the marketization of higher education, and in the implementation of tactics designed to stifle all resistance amongst faculty?

Watch the vid to see Carr instruct faculty members to rat one another one to management in order to save their jobs.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vV2ycZDHo4I

Neoliberal Higher Education | Path to the Possible

[…] as bad a misstep for our future as I can imagine. Nevertheless, there is some spot-on analysis in this article in Ceasefire by Sara Motta, even if the vocabulary is at times a bit overwrought. Share this:EmailFacebookLinkedInTwitterLike […]

On academic labour, and reclaiming academic time and space | Richard Hall's Space

[…] neoliberal subject is legitimised around specific, commodified practices that are toxic to her subjectivity, in-part through the disciplinary and enclosing nature of those practices. The REF is an example of […]

[…] Article by Sara Motta for Ceasefire. […]

Reading our Political Moment Pedagogically - Progress in Political Economy (PPE)

[…] The violences of micromanagement roll out disciplinary mechanisms and rationalities to create the ‘civil’ and ‘rational’ individualising and individualistic competitive subjects, and discipline all others. […]

Great article Sara.

A point which always strikes me in discussions within education – or indeed, any industry – over questions of “the new context” is that for all the talk of integrating academia within a “market framework”, it seems many in the upper-echelons are unwilling to question the conditions of that market; they’re accepted as rote, unwavering and immutable. The “market” is the prime operating context because the ministry of education deems it, while numerous vested corporate interests, such as SAGE and other journal publishing organisations, or indeed, the University itself force conditionalities which drive up the costs involved at every turn; far from being “realistic”, or “economic”, “austere” or otherwise, these establishments seek to drive up costs, and therefore profits, at every turn. I wonder, is the market the problem, or is it the vested interests which rig that market in their favour?

The primary tool of journals is intellectual property, naturally. By gaining monopoly rights over the intellectual product of academics, they’ve worked their way into unassailable positions. Because they’re the biggest players on the field, the impetus is to get work published in them in order to have work spread to the biggest possible audience. But at the same time, their legal monopoly means they can charge absurd amounts for access to those articles, restricting access to those economically privileged enough to attend a university whose library has access, or can afford to pay £20 per article. To me, that’s not anything like a voluntary market, that’s pure rentier behavior, using arbitrary monopolies in order to extract profits and inflate costs.

Then we’ve got the universities themselves, with all their conditions and regulations as you describe above, driving up costs, enforcing standards and blocking out all competition. The very idea of a degree as being the key to a successful career is itself problematic – it enforces a monopoly on the very concept of intelligence, success and achievement. Government standards basically determine these values, preventing any autonomous individual (or indeed, in alternative possible worlds, communities) from progressing by their own standards of intelligence and progress.

Essentially, I think questioning “economic reality” has to go far, far deeper than the cost-benefit analysis which is wracking the university system today. £3,000 versus £9,000 is the *wrong argument*. The real argument is how we can introduce higher education to the world outside the university. We need to be questioning the very concept of education as being the sole preserve of government (or indeed, corporate) accredited institutions, and knocking down the pillars of statist rentier behaviour which inflates the financial costs of undertaking educational activity far beyond the reach of anyone unable to attend higher education.

To turn the old Norse Mythology debate on its head, whether or not the state finances a supposed “luxury” we need to be asking why on earth is it so expensive to indulge our (entirely legitimate and worthwhile) academic passions in the first place. The elites dominating university administration aren’t being economic, or realistic or austere or any of those things; they’re desperately trying to find a way to continue their rentier behaviour and maintain the arbitrary monopoly on what education is, who it is for, and how it is provided.