“We are the lions, Mr. Manager”: Revisiting the Great Grunwick Strike Politics

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Wednesday, June 15, 2016 18:02 - 1 Comment

By Amrit Wilson

Walking down Chapter Road, in Brent, memories come flooding back – that hot summer of 1976 when I first met the Grunwick strikers here; the first day of mass picketing, named as ‘women’s day’, in June 1977, when the violence of the police knew no bounds. And that amazing day when Arthur Scargill came down that street leading a sea of miners…

Walking down Chapter Road, in Brent, memories come flooding back – that hot summer of 1976 when I first met the Grunwick strikers here; the first day of mass picketing, named as ‘women’s day’, in June 1977, when the violence of the police knew no bounds. And that amazing day when Arthur Scargill came down that street leading a sea of miners…

With these memories, came the questions that haunted me then: What if things had been different? What if, in the summer of 1977, against a backdrop of a mass movement, the trade union leadership had not collaborated with the state and employer? What would it have meant for us all – at the time, and for the future?

Back in the reality of Chapter Road today, the 40th anniversary of the strike is being celebrated. At the site of the Grunwick photo-processing plant, a mural is being planned, the funds raised by Brent Trades Council and local activists. It will provide, at last, a permanent and powerful reminder of those historic days.

Meanwhile, across Britain, the anniversary is being celebrated by a host of trade union organisations, setting the discourse about Grunwick in a particular mould. Almost every event will feature a screening of the film ‘The Great Grunwick Strike 1976-1978’ (TGGS) followed by a panel discussion with ‘experts’.

TGGS is a strange film. It begins with Jayaben Desai, first speaking in 2007, thirty years after the strike, when she was 74, and then through a series of photographs – as a little girl, a teenager, and with her husband in what appears to be a wedding photo. It ends, too, with Jayaben, now in her late seventies, being given an award from the GMB union.

Sandwiched in between are some sections of remarkable original footage, interspersed with interviews with some of the strikers – mainly men, even though this was largely a strike by women workers- that were also filmed in 2007, by which time much had changed in their lives. Jayaben’s son, Sunil, for example, once a worker at Grunwick, had become, by 2007, a successful businessman in Los Angeles.

Analysis is left to white male talking heads, many of whom were trade union leaders and branch officials. Jack Dromey, who was Secretary of the Brent Trades Council during the strike, and played a central role in supporting it, is there in his 21st century incarnation – never mind that in the years in between he has become a Blairite, or that, in 2005, the Transport and General Workers’ Union, of which he was then the Deputy General Secretary, sold out the Asian women strikers at Gate Gourmet, the catering firm which still serves many airlines.

Alas, neither the film, nor the panel discussions which follow, cater for those who want to know what the Grunwick strike means for us today. They do not feature, for instance, the SOAS cleaners, or hotel workers, or any of today’s other low-paid workers as speakers, nor do they compare the strike with struggles being waged in the Grunwicks of today across the global south.

If the present intrudes, it is only through the ubiquitous neoliberal gaze, which erases contradictions and nuances, turns collective struggles into individual achievement, and portrays those who are truly heroes as bland celebrities.

While seeking to glorify Jayaben, for example, the film fails to convey her deeply political analysis of strategy, or of the strengths and weaknesses of both the strike and her own community. Instead, she is made into a kind of national treasure, whose image of courage, and earthy turn-of-phrase, is what matters, not what she actually did.

At the same time, hyperbole proliferates. At the TUC Race Relations Committee commemoration, for example, a panelist declared that when Jayaben walked out in front of the massed pickets it was a moment reminiscent of Mandela being released from Robben Island! In the publicity for another event, she is described as one of two powerful women with handbags (the other was Mrs Thatcher). She is, we are told, ‘An Asian lady in a sari, a bindi always on her forehead, with a gentle voice and large, reproachful eyes.’

Even the BBC is now considering a three-part fictionalised series which aims, as a researcher tells me, to specifically ‘celebrate’ Jayaben Desai – examining, for example, ‘how she juggled family responsibilities with being the leader of the strike’.

Clearly, the racialised and gendered stereotypes portraying South Asian women as dominated by their families and passively performing household duties (even when leading a strike!) have not gone away, even as the hype round the commemorations proclaims Grunwick had demolished these stereotypes once and for all.

Largely devoid of essential context about South Asian and Black workers’ lives and struggles, or even about the political climate of the period, the commemorations present the strike as a more astonishing episode, perhaps, but also a less comprehensible one, and thus more difficult to relate to our experiences in the present.

And yet, the 70s was a period which, despite some major differences, presents remarkable similarities with how things are today. Then, too, racism was on an upward spiral, though it had not, of course, yet been reconfigured to include Islamophobia.

African-Caribbean and South Asian communities, women and men, often united at the time as politically ‘Black’, battled racist attacks, carried out not only by the National Front but by random non-aligned racists. As is the case today, they confronted police brutality and the arbitrary arrests of young black men. They also campaigned against the notorious SUS law (which was to be replaced by the equally vicious ‘Stop and Search’). They fought the pre-multicultural assimilationist education policies, which bussed even very young Asian and African-Caribbean children to schools miles from their homes to maintain racial ‘balance’.

These communities also held massive demonstrations against the 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, which aimed at excluding East-African Asian refugees; as well as the 1971 Immigration Act, which provided a blueprint for the racist immigration laws which followed – giving immigration officers the power to operate anywhere, to arrest ‘illegal immigrants’ on suspicion, and to deport people on grounds of ‘general undesireablity’. With these laws came a host of brutal procedures, the aim of which was to torture and humiliate. These notably included the notorious ‘virginity tests’, which were abandoned after a joint campaign by Awaz Asian women and Brixton Black women groups [1].

As is the case today, the 70s was also a period when the repressive machinery of the state was being strengthened in the name of “terrorism” at a time of heightened anti-colonial struggle in Northern Ireland. Draconian anti-terrorism laws were being implemented against the IRA there, as well as against Irish people in the UK.

The methods used by the notorious Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in Northern Ireland were feeding back into policing in Britain. For instance, the Special Patrol Group (SPG) in this country modelled itself on the notorious para-military organisation of the same name, which was part of the RUC. In Grunwick, it was the SPG which tore into the mass pickets.Four years later it was used in the uprisings against police racism in Brixton, and in Southall, where it was responsible for the death of anti-racist campaigner Blair Peach. The 70s also saw the establishment of state databases of activists, for the purposes of surveillance. Indeed, the Special Branch had files on the Grunwick strikers and some of their supporters, including Jack Dromey.

The Grunwick strike must also be located against the intense trade union struggles which were taking place across the country. Not only the miners’ strikes of 1972 and 1974, but a host of others in which the trade union movement and a resurgent left confronted first the Conservative government under Edward Heath and, when the 1974 Miners strike led to its fall, the Labour government under the right-wing James Callaghan.

What is sometimes forgotten by British labour historians is that this was also a time when Black and South Asian workers in Britain – men and women relegated to the lowest paid jobs in mills and foundries, or in small workplaces, manufacturing toys, sweets and light industrial goods – were often paid less than their white colleagues and were, more often than not, ignored by the trade unions. They consequently took part in several major struggles for decent conditions, equal pay and union recognition.

Indeed, there were dozens of strikes by African-Caribbean and Asian workers in the ten years leading up to the Grunwick strike [2]. In many of these, the racist Union bureaucracy and white shop stewards were the first hurdle facing the strikers. At Imperial Typewriters in Leicester, for example, the lack of support from the union forced the strikers to return to work having won only a few concessions.

This had, however, an enormous impact on the Asian women involved. According to Shardha Behen, who had arrived a few years previously as a refugee from East Africa:

“The first day I got back to work, my foreman asked me what I had gained in the last 12 weeks. He was making fun of me, I know…I told him I had learnt to fight against him for a start. I told him he couldn’t push me around anymore like a football, from one job to another. In the past, when I used to get less money in my wage packet I used to start crying…I told the foreman, ‘next time I won’t cry! I’ll make you cry!'” [3]

However, this passionate assertion of strength, and the claiming of a newfound collective identity, bringing with it a sense of hope and new possibilities, arose not only from taking a stand as exploited workers but from collectively confronting racism at work. It was also, often, about winning a struggle against the patriarchy of the women’s families and communities in order to go on strike in the first place.

This was particularly the case for East-African Asian women. In their communities – many of which had once been middle-class – women who performed what was regarded as menial work outside the home were looked down upon [1]. So while they took up low-paid jobs in Britain, out of dire necessity, patriarchal culture did not want this publicly revealed through their participation in a strike.

This struggle against patriarchy, an essential prerequisite for class struggle, was also crucial in the Grunwick strike; yet it is rarely explicitly features in the commemorations, though this part of the story, too, demolishes the “Asian women as passive victims” stereotype.

Instead, in an attempt perhaps to glorify the strikers, we are told that they were ‘steeped in anti-colonial struggle’, giving an entirely false impression. After all, while Jayaben herself, like many other Indians of her generation, often referenced Gandhi when speaking of struggle, neither she nor the majority of the other women strikers could have been involved in India’s independence movement in any significant way. She herself was only 14 when India gained independence in 1947, and she was one of the oldest among the striking women. Moreover, many of her fellow strikers had been born (and married) in East Africa, where a number of them had been housewives.

However, in the long interviews I conducted at her home, Jayaben did discuss gender. She told me, for instance, how she and a few of the other women strikers had visited the homes of many of those still working at Grunwick, encouraging them to join the strike. Distinguishing brilliantly between tradition and patriarchal ideology (though she never used the term Patriarchy), she reflected:

“I don’t think it is traditions which are weighing them down [but that] their husbands don’t want them to do anything which is not passive and the women end up believing the same…Their lives revolve round dressing up, housework, wearing jewellery and things like that”. [2]

She also told me that she belonged to the so-called ‘upper caste’ bracket of the East-African Asian Gujarati Hindu community. A look back today reveals an extraordinary trajectory for the community.

Taken to East Africa from Gujarat by the British to provide a middle-strata between Africans and the white colonialists, they had, by and large, absorbed the racial superiority over Africans which was required of them by colonialism. They were given British passports, and believed colonial promises which assured them that – armed with these documents – they would always be welcome into Britain. Of course, when they did flee from Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, the British government devalued their passports and took away their right to enter the UK. Many were ‘shuttle-cocked’ between airport lounges in various countries.

Of those who did manage to secure entry, on a voucher basis, many were destitute (although there were others who had brought their assets with them). By the mid- to late 70s, they were beginning to lead more settled lives in areas like Brent, Harrow (in North London) and Leicester. For the most part, the men got low-paid white-collar jobs, while the women joined the army of low-paid factory workers.

It was here in Britain, as a result of the racism they encountered daily, that they began to emphasise their Indian roots and create a popular discourse about India as a glorified homeland. In the 90s, when India began to implement neoliberal economic policies, and the BJP – a Hindu supremacist party rose to power by shaping itself around neoliberalism – this community provided a base for it in the UK [1]. Today, Islamophobia is rife among the community, and the imagined India many would like to see emerge is a fascistic Hindu state.

Ironically enough, back in the 70s, Hindus and Muslims were united against racism. At Grunwick, it was racism, and attacks on their dignity, which the workers found most unbearable. The firm recruited specifically from among the refugees, demanding passport numbers and dates of arrival in the UK. As for the racism, as Jayaben told me:

“Imagine how humiliating it was for us, particularly older women, to be working and to hear the employer saying to a young English girl ‘You don’t want to come and work here, love, we won’t be able to pay the sort of wages which will keep you here.'” [2]

George Ward, the owner of Grunwick who during the strike had the support of two Tory MPs as well as that of the extreme right think-tank the National Association for Freedom (NAFF), was an Anglo-Indian himself. According to Jayaben, he would taunt them in ways which he knew would be most hurtful, while any accusation of racism against him was met with a libel suit financed by NAFF.

The factory had glass cabins on both sides, through which the management could keep a close eye on the workers, pushing them to work faster and faster, while threatening them with dismissal if they failed to keep up. Sick leave was unheard of, and the women had to ask permission even to go to the toilet.

On the day when the workers walked out, the line manager had compared Jayaben and her colleagues to ‘chattering monkeys’. She famously replied:

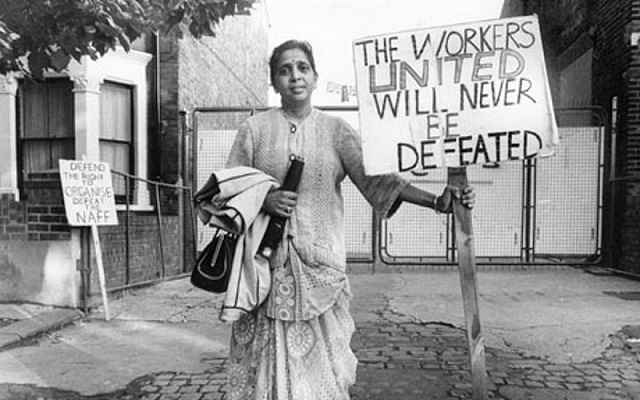

“What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. But in a zoo there are many types of animals. Some are monkeys who dance on your fingertips, others are lions who can bite your head off. We are the lions, Mr. Manager.”

The strikers joined the Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff (APEX, today merged with the GMB), and soon afterwards asked APEX to approach the Union of Postal Workers (UPW) to Boycott Grunwick’s mail. Since the firm was dependent on postal services for delivering finished photographs, a boycott would have completely paralysed it, leading to victory for the strike. However, as Mahmood Ahmad, secretary of the strike committee, told me, APEX refused to approach the UPW for solidarity action [although this would have been perfectly legal at the time]. [2]

In November 1976, bypassing APEX, Jayaben approached the postal workers at Cricklewood directly, and they started boycotting Grunwick mail. At that point, the strike could have been won within weeks. However, Ward and his supporters in the NAFF took the postal workers to court, and despite the legality of solidarity action, the judge ruled against them. The action was soon called off by Tom Jackson, General Secretary of the UPW. Meanwhile, APEX approached the government’s conciliation service, ACAS, but Ward predictably refused to negotiate [2].

The strikers, with the help of Brent Trades Council, then worked on a new strategy. Realising that they were going to need mass support, they undertook a tour of the country, speaking to workers in thousands of workplaces. In June 1977, after nearly a year on the picket line, the strike committee sent out a call for support.

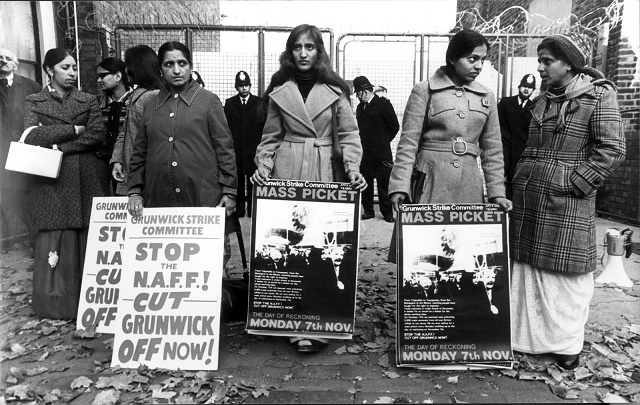

The response was immediate and amazing: Workers from across the country – miners from Yorkshire, Scotland and Wales; engineers; steelworkers; print workers; and many other trade unionists, as well as left, feminist and anti-racist activists – all flocked to the picket line. The number of pickets steadily increased over the subsequent few weeks, as did the violence of the SPG. Hundreds of people were injured and hundreds more were arrested. For their part, the media, though constantly challenged by print workers, focused entirely on the ‘violence of the pickets’.

And yet, victory seemed almost inevitable, and would have been achieved on the back of a massive and united movement against the state and employers. This was a potentially revolutionary situation, but the British left; the Socialist Workers Party, Communist party and a number of other left parties, who were all involved in supporting the strike, had no strategy for such revolutionary change.

This was when the right-wing trade union leadership revealed its true colours. APEX (described by Dromey in the film as having given the strikers ‘enormous support’) called for a limit to the number of pickets! The TUC issued an edict condemning ‘irregular elements’ on the picket lines, which were supposedly dividing and deflecting ‘support given by responsible trade unionists’. Meanwhile, the Cricklewood postal workers were laid off by the Post Office and threatened with withdrawal of their strike pay by the UPW (Eventually they were to be fined and disciplined for disobeying union orders) [2].

As a way of pacifying the strikers, the government set up a Commission of Inquiry under Lord Scarman. As with the earlier report by ACAS, this too eventually sank without a trace, though it did fulfil its purpose: sapping the momentum out of the struggle. It was as though the time for solidarity had suddenly passed. Even left-wing unions had suddenly turned their attention to other things.

In a typically hypocritical move, however, the strikers were invited to the Labour Party Conference that autumn, and even received a standing ovation. But the solidarity action and boycotts they desperately needed were, of course, no longer available. Soon after, four members of the strike committee, including two women – Jayaben and Yasu Patel – staged a hunger strike outside the headquarters of the TUC. They were immediately suspended by APEX and had their strike pay stopped. Jayaben said at the end of the hunger strike, “The union just look on us as if we are employed by them. They have done the same thing to us as Ward did…’ With regards to the TUC, she added:

“They make the rules…we can’t make any hunger strike, we can’t make any demonstration, we can’t make any mass picket, we can’t do anything. Now it means they are going to tie the workers’ hands. We shall have no chance to do anything…it will apply to everybody, not just to the Grunwick strikers.” [4]

She was right. When Margaret Thatcher came to power, less than two years after the strike had ended, she introduced a raft of anti-trade union laws, including a ban on solidarity strikes and mass pickets. Today, insecurity, precarious work and zero-hours contracts have been normalised in Britain. At the same time, the new racialised division of labour has seen workplaces like Grunwick – sweatshops and industrial component factories – being relocated to countries of the global south.

What low-paid work is set to remain in Britain is mainly in the service sector work, which cannot be relocated – cleaning, hotel work, domestic work, nursing – where the workers are often refugees, or people with insecure immigration status, who are supporting families back home in Africa, Asia, or Latin America.

Many of these workers have had experience of organising in their countries of origin, and a large proportion are women. Even in these harsh conditions, they are fighting for basic rights and justice, and in these struggles race and gender are centre stage. If the trade union leadership, still mainly male and white four decades after Grunwick, fail to support them, then it may as well admit its irrelevance.

an excellent article. i wonder how much progress we have made on the trade union front. There may not be so much racism about but the work conditions and the trade union attitude has not change much. the call centre workers even in this time and age are treated more or less the same as in Grunwick. I know a woman who works in one and she is required to put a box on her seat when she goes to toilet. I could not beleive it. As far as the trade unions are concerned, they are mostly interested in the short term interest of themselves rather than the workers they represent. I briefly got involved in the local co-op when it was in trouble and Lord Myners came to rescue it. he was proposing fundamental changes which were totally against th co op principles but he managed to get the trade union reps on board and as you know the result is that the co op ended up selling all the profitable businesses etc.