Review | Unmaking Merlin: Anarchist Tendencies in English Literature (Zero Books) Books

Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, March 27, 2015 0:00 - 3 Comments

By Tom Malleson

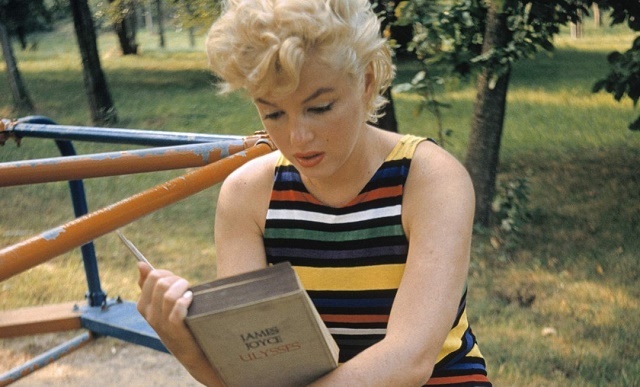

Marilyn Monroe Reads Joyce’s Ulysses at the Playground (Eve Arnold, 1955)

Recent years have seen a renewed interest in anarchistic thought and theory. The upsurge is apparent across different types of media, from academic scholarship (such as David Graeber and James Scott) to popular writing and journalism (such as Arundhati Roy and Naomi Klein). Yet since most of this writing tends to emerge from the traditional strongholds of politics, philosophy, and anthropology, it is refreshing and exciting to see Elliot Murphy bring an explicitly anarchist lens to bear on English literature.

Murphy is remarkably erudite for such a young scholar. Though not even 25 years old, he zooms with apparent ease and familiarity from George Orwell to Friedrich Nietzsche to James Joyce to Christopher Hitchens. The central aim of the book is to “focus on the neglected and repressed indigenous anarchist tradition of the British Isles” (ix). And indeed, the strongest parts of the book are those that highlight the anarchist tendencies half-buried in well-known writers, including Orwell, Joyce, and Powys. Murphy demonstrates that even if few writers explicitly embrace the label “anarchist,” English literature is nonetheless rich with anti-authoritarian ideas.

The book is wide-ranging, touching on a number of themes – including education, representative democracy, the New Atheism, corporate power, crime, and poststructuralism. Throughout, Murphy does a good job of showing that the popular association of anarchism with violence and chaos is deeply inaccurate. He shows that the central concerns of anarchists have always been self-determination, mutual aid, and an end to structural violence.

The biggest weakness of the book is structural. Instead of developing an overarching argument that could be built up systematically, the narrative flies around from topic to topic, presenting the reader with a dizzying pastiche of ideas, facts, and tangential arguments. The first few pages of Chapter 2, for example, mention in rapid-fire succession: Dickens, Huxley, Humboldt, Ruskin, Friere, Darwin, Mirandola, Le Guin, and on. The problem with such speed, of course, is that what is gained in breadth risks being sacrificed in depth.

A deeper problem is that some of Murphy’s tangents are into areas which are clearly not his forte. The digression into poststructuralism, for instance, felt particularly unnecessary. There is, of course, much room for honest disagreement about whether Kuhn, Feyerabend, and Latour have added anything to our understanding of science, or whether Foucault has anything useful to say about power, or Butler on gender, or whether the whole anti-realist tradition from Nietzsche to Heidegger to Rorty, has anything useful to say about truth and objectivity. But to bring up and summarily dismiss such broad traditions in so few pages is unlikely to persuade anyone of anything.

The text as a whole would have been more compelling if there were fewer tangents (less polemics against Christopher Hitchens or the poststructuralists), and more focus on the literary figures that are the author’s chief area of expertise. To his credit, Murphy discusses many literary giants including Blake, Ruskin, Woolf, Morris, Wilde, Orwell and others – all fascinating anti-authoritarian writers – but rarely with the comprehensiveness they deserve.

In particular, the fact that Tolstoy and Le Guin – surely giants of anarchist literature – receive such passing treatment is somewhat odd. What of Le Guin’s works other than The Dispossessed? What of Tolstoy’s short stories, such as “How Much Land Does A Man Need?” and “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” – both great works overflowing with anarchistic sentiment? (Perhaps the Russian Tolstoy does not belong in a work ostensibly about literature from the “British Isles,” but then it’s hard to explain why the American Le Guin does).

More than anything, I wish Murphy had talked more of contemporary literature. Since the 1994 Zapatista rebellion and the 1999 Battle of Seattle, anarchist ideas are more prominent than any time since 1968. How has this political surge been reflected in literature? That is an intriguing question. One to which I do not know the answer, and which Murphy’s book could have done more to illuminate.

More than anything, I wish Murphy had talked more of contemporary literature. Since the 1994 Zapatista rebellion and the 1999 Battle of Seattle, anarchist ideas are more prominent than any time since 1968. How has this political surge been reflected in literature? That is an intriguing question. One to which I do not know the answer, and which Murphy’s book could have done more to illuminate.

All in all, much of what Murphy says of anarchism is true and interesting. The book does not always live up to its potential, but this is one author whose future works I await with much anticipation.

Review of Unmaking Merlin: Anarchist Tendencies in English Literature

Elliot Murphy

Published 2014

Winchester: Zero Books

3 Comments

The Craft of Novel Writing by Dianne Doubtfire – (Part 1) | InstaScribe

Review | Unmaking Merlin: Anarchist Tendencies ...

[…] While recent years have seen a renewed interest in anarchistic thought and theory, it is refreshing and exciting to see a new volume bringing an explicitly anarchist lens to bear on English literature, argues Tom Malleson in his review of 'Unmaking Merlin: Anarchist Tendencies in English Literature' by Elliot Murphy. […]

The Craft of Novel Writing by Dianne Doubtfire (Part 1) |

[…] Books | Review | Unmaking Merlin: Anarchist Tendencies in English Literature (Zero Books) […]

[…] Books | Review | Unmaking Merlin: Anarchist Tendencies in English Literature (Zero Books) […]