Review | ‘Protest: Stories of Resistance’ Books

Arts & Culture, Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, October 22, 2019 10:03 - 0 Comments

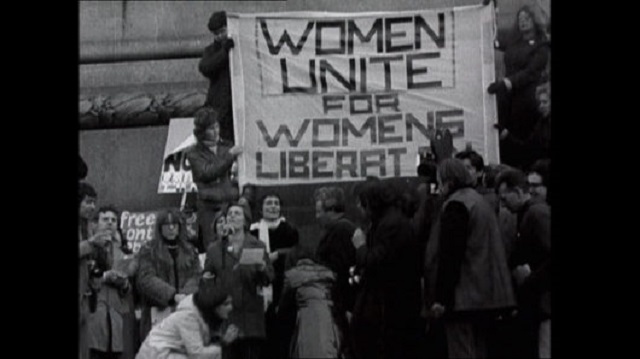

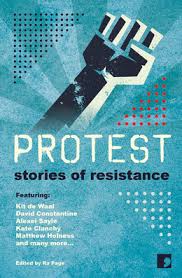

“Whatever happened to the art of British protest?” asks the back-cover blurb to the short story anthology ‘Protest: Stories of Resistance’. In fact, the collection demonstrates, through vital and timeless narratives of real protests, the endurance of this art over the centuries.

The book covers protests against a wide range of socio-political issues, which remain deeply relevant to British society today: from relentless far-right anti-immigration demonstrations since the Brexit vote, to immense cuts to disability benefits under the Conservative government’s austerity programme. Each story has an afterword providing context to its protest, of which the writer has specialised – sometimes personal – knowledge, anchoring the stories further within historical reality (these experts also consulted on the stories themselves).

Many protest scenes strongly evoke the atmosphere of their historical moments, despite clear common themes between different protests throughout the collection. Courttia Newland’s ‘That Right to be There’, on the 1989 poll tax protest-turned-riot, powerfully conveys the sense of overarching bitterness which characterised Thatcher-era protests, combined with the fun, weed–and-alcohol-fuelled side of this culture.

Newland adopts a trope more often applied to school prom nights, or idyllic road-trips – an uptight, introverted male protagonist seeing these events with fresh enthusiasm due to an enigmatic, free-spirited female love interest – to the decidedly less conventional setting of a protest, rendering his story familiar and thus accessible to (not necessarily politically-minded) young adult readers.

The story perfectly captures the oft-seen contrast between the reckless rage of protesters – and the police – and the glamorous aesthetic of central London. As the riot finally dies down and the protesters remain reflective in Trafalgar Square, Newland emphasises ‘their connected pasts’ encompassed there: A collective history of injustice and corresponding public dissent, the side of London that defies commodification as a tourist attraction.

Like Newland’s Chris, several protagonists are initially somewhat outsiders at these protests on which they find themselves – having been dragged along by lovers, exes, or friends – and gradually become caught up in the infectious atmosphere of resistance and unity against oppressive establishment policy and/or immediate police (or military) violence.

As editor RA Page’s introduction argues, pervasive feelings of helplessness are often excluded from mainstream narratives around historical struggles. Through the short story form, Protest centres marginalised and erased voices, including real historical figures – refreshingly human, allowed to be uncertain, powerless, even passive towards the protests – rather than constructing idealised heroes based on ‘“great men”’.

Indeed, one intriguing aspect of Protest is the variation between protesters, and the ideologies behind their dissent. Sara Maitland’s ‘The Pardon List’, for instance, describes – through the voice of an unflinching female protagonist – the religious glory felt by villagers during the 1381 peasants’ revolt, using Christian discourse to counter the deeply entrenched inequalities of feudal medieval English society.

Meanwhile, Jacob Ross’ haunting ‘Bed 45’ recalls the Brixton riots (exactly 600 years later), which protested the authorities’ disregard for Black lives, through the eyes of a doctor mourning a son lost to brutal police violence – an enduring feature and trigger of protest harshly recognisable in the 2011 London riots and countless other protests this century.

Many of the protests ultimately help rectify, destroy, and/or underline pre-existing conflicts in relationships. Kate Clanchy’s ‘The Turd Tree’, on the 2003 Iraq war demo, uses a neat personal metaphor to convey the magnitude of Tony Blair’s decision to invade Iraq, as Laleh Khalili’s afterword suggests. The shattering of the protagonist’s naïve faith in British democracy coincides with the discovery of her love interest’s betrayal; the story culminates in a visual fusion of personal and political which forces her out of complacency at both levels.

Several contributions, for example Maggie Gee’s ‘May Hobbs’, create a dialogue between different time frames, with characters reflecting – or discovering information – on major protests several decades later, emphasising the lasting impact of these timeless struggles on subsequent generations facing new socio-political injustices. Set just before Trump’s election in 2016, Gee’s story centres on three female characters with various connections to Hobbs and the 1971-2 night cleaners’ strike, projecting the voices of striking women cleaners through one character’s research.

In this intergenerational tale of women’s relationships with politics and the mingling of personal and political in working-class women’s lives, Gee exposes an age-old contradiction: the workers most central to workers’ rights campaigning are often excluded from discussions of these issues due to lack of resources such as reading materials. One protagonist concludes that ‘the educated kept good things to themselves’.

Other stories similarly present tensions between protesters of different class backgrounds within the same struggles, exposing the pretentiousness of educated, artsy pseudo-revolutionaries against the backdrop of such protests as the 1968 anti-Vietnam war demo and the Aldermaston marches against nuclear weapons (c.1950s-60s).

Joanna Quinn’s ‘The Stars are in the Sky’ is another story of women’s activism – the 1980s Women’s Peace Camp against nuclear weapons being placed in Greenham Common, Berkshire. Whilst not women’s rights-specific, this movement is portrayed as deeply feminist, allowing diverse women to protest indirectly against their own oppression through a wider political campaign (as real-life participant Lyn Barlow’s afterword describes). Dismissive reactions from locally-stationed soldiers, brutal violence and overt sexual harassment from the police, and patronising remarks from journalists are all facts of life at Greenham.

However, equally central are the day-to-day demonstrations of friendship and solidarity between the women. Despite being a site of dangerous weapons, Greenham functions as their safe space: they hang precious items on the fence and bond over their husbands’ lack of understanding. Quinn sensitively explores the inner conflict of juggling motherhood with activism: her protagonist feels both ‘the guilt of having [children]’ and ‘the guilt of having left them behind’. As in many of these stories, protest functions as the protagonists’ cathartic escape from social suffocation – here, within marriage and domesticity.

The intersection between patriarchy and other forms of marginalisation is a recurring theme of Protest. Sandra Alland’s fascinating story of a lesser-known movement – early 20th century Blind rights’ activism – notes the gendered limitations of these campaigns, while Laura Hird’s ‘Spun’ on the 1820 Radical War underlines women’s inability to participate in strikes through one rhetorical question: ‘My workplace is [at home], does that count?’

Despite Protest’s undeniable diversity, with protagonists including (not always distinctly) women, BAME, LGBTQ+, working-class and disabled people, several protagonists are strikingly privileged. Clanchy’s comfortably middle-class, white protagonist, once an activist, now mourns her youthful idealism; David Constantine’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ is narrated by two similarly nostalgic elderly white ex-activists, reflecting on the May Day March against the titular speech, and their marriages to (now deceased) foreigners, in intellectual and historical terms.

These spouses – along with the hundreds of thousands of BAME people targeted by Enoch Powell’s speech – are not granted their own voices. As sensitively as these two stories are told, it would be refreshing to see the perspective of a character with first-hand experience of the racism and/or resultant warmongering being protested.

Further, whilst some stories do centre BAME characters – including Newland, although race is not his sole focus – not one mentions a protest led by women of colour; such landmark campaigns like Grunwick are excluded. The collection has also been criticised for being highly Anglo-centric, with very few stories set elsewhere in Britain. Incorporating more BAME, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish perspectives, just as captivatingly authentic as those at the heart of many of its existing stories, would potentially render Protest even more powerful.

Further, whilst some stories do centre BAME characters – including Newland, although race is not his sole focus – not one mentions a protest led by women of colour; such landmark campaigns like Grunwick are excluded. The collection has also been criticised for being highly Anglo-centric, with very few stories set elsewhere in Britain. Incorporating more BAME, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish perspectives, just as captivatingly authentic as those at the heart of many of its existing stories, would potentially render Protest even more powerful.

Protest: Stories of Resistance

Editor: Ra Page

Contributors: Featuring Sandra Alland, Martyn Bedford, Kate Clanchy, David Constantine, Frank Cottrell Boyce, Kit de Waal, and others

Comma Press, 2017

Leave a Reply