A fork in the road Quebec Chronicles

New in Ceasefire, Quebec Chronicles - Posted on Wednesday, July 4, 2012 15:53 - 0 Comments

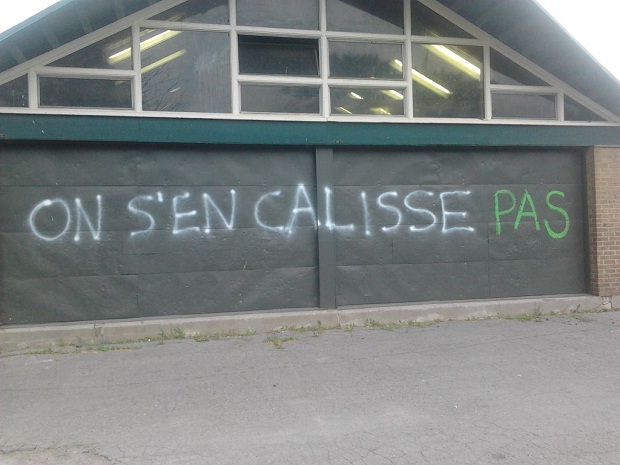

Maple Spring graffiti modified by a member of the anti-strike camp (Credit: Jane Gatensby)

On a wall in Montréal’s Rosemont neighbourhood, the debate rages on: a piece of Maple Spring graffiti has been modified by a member of the anti-strike camp, identifying himself by the use of green paint. Loosely translated, the conversation goes something like this: Graffiti artist #1- “F*** [Law 78]”, Graffiti artist #2- “Don’t!”.

As the Maple Spring slips into a long, hot summer, Quebec questions where exactly to go from here. This month, the student movement continued to simmer with disruptions at the Montreal Grand Prix and another Manifestation Nationale, the political establishment geared up for coming elections and Quebecers of all stripes continued to debate, discuss, and theorise about Quebec’s recent social upheaval.

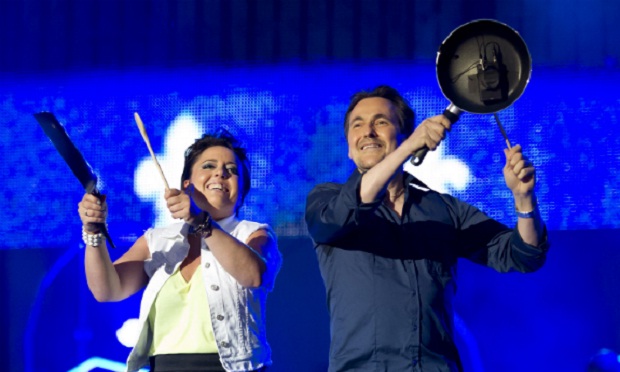

Ariane Moffatt and Guy A. Lepage bang casseroles during St. Jean Baptiste Day celebrations. (Source: 7jours.ca)

June 24th marked Quebec’s fête nationale, St-Jean Baptiste Day. Coming at the end of a heatwave, St-Jean festivities once again brought hordes of patriotic spectators to Parc Maisonneuve in eastern Montreal. As master of ceremonies, entertainer Guy A. Lepage didn’t shy away from using the ever-present social conflict (born of the Quebec Liberal Party government’s planned tuition hikes and the anti-protest, anti-student strike Law 78) as material.

Lepage’s choice of subject matter spoke to just how pervasive the debate has become here – imagine Ricky Gervais making jokes about neo-liberalism at a variety show, and people actually knowing what he was talking about, and you’d get a good picture of Quebec in 2012.. Equally telling were the large number of red squares (a show of support for the student movement) worn by performers and tacked onto fleurdelysé flags in the crowd. St-Jean marked a brief reprise in a month of increasing division and endless discussion over what this months-old conflict means for Quebec’s future.

The Montreal Grand Prix

Protesters give tourists a taste of Montreal’s social upheaval during the Grand Prix. (Credit: Nicolas Quiazua)

Wanting to put economic pressure on the government during Montréal’s lucrative summer tourist season, the CLAC (Convergence de luttes anticapitalistes) were joined by night marchers in various attempts to disrupt the event, which took place between June 7th and 10th. Media coverage of the student protests and US government travel warnings are said to have contributed to this summer’s steep reduction in tourism, and those who did come to the city to see the race were not spared from seeing the conflict, as protesters clashed violently with police lines downtown, with smoke bombs and broken police windshields.

Videoclip shared on social media encourages students to disrupt the Grand Prix.

On the morning of the Grand Prix’s debut, Montreal Police conducted arrests of eleven student activists in connection with attempts to sabotage the Montreal Metro and with the ransacking of ex-education minister Line Beauchamp’s conscription office in May. Among those arrested was Yalda Machouf-Khadir, daughter of Amir Khadir, a high-profile representative in Quebec’s National Assembly. He himself had been arrested less than forty-eight hours earlier for participating in a march in Quebec City that was declared illegal by police.

Allegations of police profiling at the race itself, held just a short Metro ride from the city centre on Sainte-Hélène-Island, were confirmed point-blank when two journalists wearing red squares for investigative purposes were held and questioned by police at the site, and were eventually denied entry because of their purported “criminal intentions”.

According to messages from the student federation CLASSE (Coalition large de l’association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante) and other groups, the Grand Prix was worthy of being denounced because of the sexism and elitism inherent to it, an argument not entirely countered by the large number of scantily-clad women working in promotional booths during the event, or by millionaire racecar driver Jacques Villeneuve saying to reporters at a Grand Prix cocktail party that striking students should ‘’go back to school’’.

Indeed, the clash of values between student protesters and Grand Prix organisers seems to have been what prompted this event to be targeted over others held this month. The Francofolies music festival, for instance, was spared from disruption entirely, and on June 15th, leaders from the three main student federations (FEUQ, FECQ and CLASSE) were invited onto its main stage to join Québecois rap group Loco Locass in a now-infamous rendition of Liberez-nous des libéraux [Free us from the Liberals] to the clamour of casseroles.

The Student Movement

With many students away from Montreal for the summer or working full-time jobs, mobilisation has slowed somewhat in the student movement. Night marches are dwindling in numbers and fewer than 15 000 people attended the fourth consecutive Manifestation Nationale on June 22nd in Montreal (In Quebec City, however, the event set a record with as many as 10 000 marchers).

The Student Federations themselves have been maintaining a steady presence, with the Féderation étudiante collégiale du Québec (FECQ) calling for the government to accept their demands and bring in a mediator before the semester resumes. As provided for by Law 78, classes will be given in August no matter what, for students who were still on strike at the end of the winter session- whether student associations will again vote to strike and block classes in spite of the law’s far–reaching measures is another matter.

Despite the UN calling Law 78 “alarming” for civil liberties, student federations were disappointed on June 27th when attempts to challenge the law were struck down by Quebec’s superior court. The law’s provisions include suspending funding to student federations should their member associations decide to picket, something that CLASSE’s Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois calls “a direct attack on liberty of association”.

Looking Inwards

Writer Dany Laferrière once equated Quebec’s identity problems to the melancholy of too many winter months spent inside, saying, ‘’I’ve never seen a debate in Quebec in July’’. The way things are going this Summer, his statement is not likely to hold true. In what is now the fifth month of the student crisis that is now more often called a social one, it’s difficult to avoid the daily mountain of commentary trying to explain the current climate here.

Seventeen years after the incredibly close referendum on sovereignty that marked Quebec’s last big upheaval, a new national debate is taking centre stage; the decades-long discussion between ‘sovereigntists’ and ‘federalists’ has faded into the background. Left and right now determine the dividing line, and both sides are finding themselves in uncharted waters.

Toward a change?

Polling suggests that Quebecers want an election, and Jean Charest is expected to call one around August. The new left-right discourse will make this election quite different from the rest: votes have typically been split between the sovereigntist Parti Quebecois (PQ) and the federalist Liberals.

Sovereignty will remain a factor, however, and the rift between newly-radicalised young voters and their parents’ generation will also have its effect. The Journal de Montréal’s Richard Martineau highlighted an additional division likely to come into play, between Montreal voters and those in the rest of the province, who see the debate in Montreal as “ideological” and “disconnected”.

Premier Jean Charest explains his stance in the English version of a much-parodied Quebec Liberal Party TV spot.

In parliament and in recent pre-campaign messages, the Liberals Have tried to demonise Pauline Marois, the pro-student leader of the Parti Québecois, by equating the red square she is known to wear in parliament with “violence and intimidation”. They released an ad (now pulled due to copyright issues) earlier this month showing slowed-down, black-tinted video of Marois participating in a casseroles demonstration, its Blair Witch-style spookiness leaving most commentators unimpressed.

Marois, who stopped wearing the red square mid-month, appeared in her own ad calling for Quebecers to come together despite their differences to celebrate la fête nationale. The two parties were neck-and-neck in the polls at the beginning of the month. Amir Khadir’s leftist Québec Solidaire party expects to capitalise on the student movement’s vision of a reformed democratic system to gain deputies, while the newly-formed Coalition Avenir Québec presents a centre-right alternative without a federalist agenda.

Despite all the division, Quebecers mostly seem to agree that the Harper government, currently in power in Ottawa, is not for them. In a piece whose title roughly translates as “Québecois under the microscope”, Le Devoir columnist Lise Payette explained that last April’s “orange wave” (when Quebec voters supported the socialist New Democratic Party for the first time in a Federal election, abandoning the sovereigntist Bloc Québecois) showed that Quebec had a desire for change, but also that it felt the need to counterbalance the policies of Western-Canadian conservatives with whom they feel they have little in common. She also warned that Quebecers’ “fear of breaking eggs to make an omelette” had a chance of ensuring a fourth consecutive Liberal victory come election season.

Commision Charbonneau

This month saw the first round of testimony in the Charbonneau commission, a provincial inquiry into the management of public contracts in the construction industry, intended to shed light on rampant corruption and links between provincial and municipal politicians and organised crime. Now suspended until October, the commission’s most shocking revelation (and there were many) came from the former head of the Quebec Police’s anti-corruption unit, who claimed before the judge that seventy per cent of provincial campaign donations come from “dirty money”. His words have since been contested, especially by the PQ.

The corruption issue has been a rallying point for the student movement’s supporters, who say that the government should manage its money more wisely before making students pay. In an open letter published in Mauvaise Herbe magazine, architect Jean-Benoît Tremblay, who says he took out thousands in student loans to obtain his degree, lamented the corruption he faces while exercising his vocation, saying:”The transportation minister [Pierre Moreau], as if by accident, is currently fast-tracking public contracts to get them out of the way before the Charbonneau commission sheds lights on the dishonest and wasteful way we use our money to line the pockets of the Mafia […] they let millions and billions be stolen and now they dare to tell us that there’s not enough money, that it’s time to tighten our belts, that the students need to pay their fair share! That’s called disinformation, and too many media outlets are taking part in it.”

_________________________

“Quebec is at a fork in the road. Personally, I’d go left. But ideally, this road will become a common path again soon”

These words, Guy A. Lepage’s closing remarks at Parc Maisonneuve, speak to the feelings of many Quebecers when it comes to the conflict. But with so much hanging in the balance, it’s likely that Quebec’s current troubles will take some time to play out.

Leave a Reply