Mexico: after the election, the resistance Special Report

New in Ceasefire, Special Reports - Posted on Tuesday, July 3, 2012 2:18 - 0 Comments

By Ali Sargent

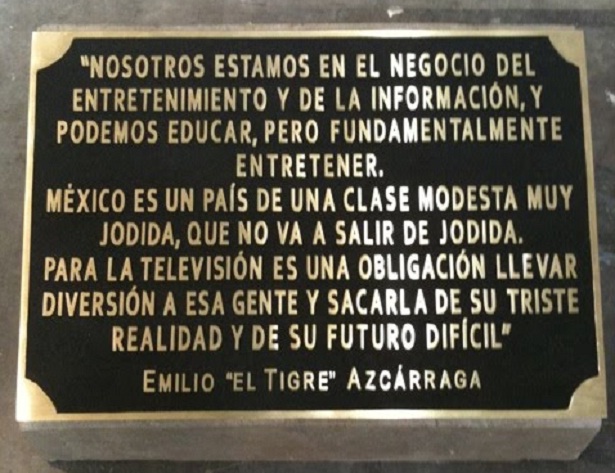

Plaque in the lobby of Televisa HQ “We are in the business of entertainment and information, and we can educate, but fundamentally we can entertain. Mexico is a country of a very modest class that is entirely screwed, that is not going to stop being screwed. For television it is an obligation to bring diversion to people, to bring them out of their sad reality and future difficulty.”

The stage was fatally set for Mexico’s elections. On Wednesday, 4th July, the country is expected to hand state power to the PRI, a party who ruled a “perfect dictatorship”, with what some describe as a ‘soft iron fist’, for 71 years. It is the parents and grandparents of Mexico’s current youth that saw the worst of state repression. Now they return with the sparkling ivory bite of Enrique Pena Nieto.

This election comes at almost the same time as it US equivalent, yet only poet Javier Sicilia’s “Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity” has emphasised the opportunity for pressure and dialogue over the countries’ intertwined problems, notably narcotrafficking and migration.

This inevitable truth has been evident for some time; however, what happens at the elections is more about the relation the people will have with their president i.e. whether Mexican citizens will let the country trudge slowly back to dictatorship. This question presents itself most clearly through the voice of recently mobilised youth resistance. Yosoy132 have been the most visible exponent of this resistance, gathering in a matter of months to protest the media manipulation of the elections and target the PRI party in particular.

It began as a confrontational protest at the Ibero-American University, a private university in Mexico City. It was the only university visited by Pena Nieto, commanding some of the highest tuition fees in Mexico. He was mobbed as he entered, with shouts of “Murderer!” “coward!”.

During the debate questions were raised regarding Nieto’s decision to use repressive state force at an EZLN uprising in San Salvador Atenco in 2006, where he was state governor at the time. The Supreme Court of Mexico recognised it as an instance of grave violations of human rights; amongst recognised complaints are 2 deaths, the rape and sexual abuse of 26 women, torture and arbitrary detention. The episode had become a mark of trauma in Mexico’s recent history.

Amongst the shouts that forced the candidate to flee the campus were “Atenco!” and “We remember!”. The video then circulated on Youtube. The PRI covered their ears, claiming the students were paid imposters, and – worse – supporters of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the main candidate of the Left.

To prove these were false accusations, the 131 students posted videos on Youtube of them holding their student IDs. The group of students that united in support, from both state and private universities, called themselves Yosoy132.

The movement quickly spiraled, and the marches drew tens of thousands. Two non-student marchers told me at one, “Mexico has a long history of student activism, and we’re really proud of that. We’re glad the students started this, and glad to participate. It is beyond students now.”

The movement seemed savvy and technologically focused. There were social networking sites, Youtube channels, a smartphone app, a documentary, and a debate organised with the presidential candidates. Pena Nieto declined to attend but Camila Vallejo, the admirable and influential Chilean student leader, met with the leaders to help solidify their goals and tactics. Marches took place all over Mexico.

Soon came the international scandal of Narco News and The Guardian’s allegedly leaked documents that uncovered an agreement between Televisa, one of Mexico’s two main television channels, and the PRI campaign to purchase positive press coverage. Televisa is Latin America’s biggest multi media company, a pervasive force. Unsurprisingly, they did not cover the university protest, or the marches.

“Look around us. Nobody here [in Mexico] even knows about the Televisa allegations,” Manuel, the leader of the student group Estoy Despierta tells me. The group released an open letter to the Mexican people which became a plangent manifesto. It is eloquently written, and is currently being released to the press translated in five languages. The idea is that it could have been written by any Mexican. That their concerns are those of many others. “A large part of our political class have betrayed the width and breadth of our country without a care” says manuel “they have ceaselessly scorned our intelligence, aspirations and dreams in favour of individual benefit.”

“I know the information from international media often doesn’t get to us,” Manuel continues. We want people to realise the weakness of the Mexican media compared to international media.“

Yosoy132 held marches to Televisa HQ and media manipulation was a key theme in their discourse. The final march to Televisa HQ before the elections saw a surreal scene of tears from the policemen guarding the gates.

However the movement shows signs of fracture, with one leader ousted for ties to Lopez Obrador. The group’s members have stressed their plurality, and none of the student groups wish to claim ideological focus. Indeed, Yosoy132 have yet to state post-election plans.

The Mexican public face an intricate and disorientating web of social and political problems. There is widespread cynicism towards politics; a sense of redundancy threatens a much-needed fight that does not quite know its enemy. Capital rules all. Politicians forge expensive alliances with the media and leaders of some of the world’s biggest syndicates; a Youtube video shows gifts awaiting community leaders in poor areas to ensure votes for PRI; the media is monopolised by two companies, Televisa and Azteca; the street price for killing someone is said to be 3,000 pesos (around 150GBP).

So Yosoy132’s targeting of Pena Nieto looks a little narrow. One activist, who was also personally involved in the PRI campaign tells me; “their budget reveals a couple of million officially assigned to billboard and television adverting. But there’s millions more spent in hidden ways.“

Mexican democracy is not yet a teenager, but has grown up fast and has some fairly strong institutions. Many activists are conscious it is the murky culture at the interface of media, corruption and politics that limits people’s freedom to deliver an informed, confident vote.

93% of Mexicans have a television in their house, but content is controlled by two companies. 77% of Mexicans receive their information through television, which is mostly a gleaming stream of telenovelas.

Estoy Despierto focus on democratisation of the media to force a more accountable, transparent politics. Their aim is to establish ‘citizen observation’. The fight for information for all, for them, incorporates the need for better education.

“Information should be a universal right for us. Information for all would give us better ways to solve other problems,” argues their leader. Their faith lies in the internet as the most efficient means of change. Mexicans form the fifth biggest demographic of Facebook users. However, 80% do not have access to internet at home (89% do not in Egypt). A website will be launched by the group so as to allow citizens to disseminate information and proposals about Mexican reality, thus helping bring media democratisation a step closer.

International media is also key to Estoy Despierto’s plans, allowing them to bypass Mexican mainstream media. However, stories from Latin America told by foreign media often fail to grasp the complexities of the local realities, simplifying them for unfamiliar perspectives.

On the screen, of the many faces of Mexico the international community sees only reduced narratives of the “War On Drugs”. Behind the screen it is fundamental that Mexicans open up their own dialogue, and not just – as Manuel puts it – “to fight to protect the image of Mexico”.

Another activist sees this as part of Estoy Despierto’s work. “It’s the culture and mentality we have to change. If people think this government is going to do anything for them, they’re wrong. This is about getting people in their community to implement changes.”

Manuel says “it’s important activists stay in these small core cells, acting for themselves. That way it will be harder for the government to destroy us.” The PRI are already perhaps onto this. On Facebook, young Mexicans talk of a list compiled by the PRI of anti-PRI activists.

However, part of the reason the PRI have largely declined to comment on movements such as Yosoy132 is perhaps the fact their nexus is in the urban population of Mexico City. However, the group has demonstrated a wider awareness; a march this week culminated in San Salvador Atenco and their coordinated demonstrations have taken place in several Mexican states.

Communication should not be conceived as only focused through the internet. Neither should social organising. Such an approach will limit the movement to more urban middle class adherents, who form the bulk of the 20% of the population with ready internet access.

Estoy Despierta want more available internet for all, but also need consider the valuable perspective of non-urban populations. Whilst it may be true that the majority of Mexican population lives in cities, many are migrants from the country. Furthermore, it is those in the country who excel in autonomous resistance, possess distinctive knowledge and have experienced the worst fallout of some of the government’s negligent and incompetent policies.

When I ask Manuel about this he is sceptical, “to speak to people such as campesinos will take longer. That is in the future. Right now the target is the media. We want people to wake up, to speak the message: imagine what we can do with hundreds of small groups like this.”

From Zocalo (Mexico City’s main square) yesterday a giant eye gazed across the sky. A few days earlier, giant writing outside the Bellas Artes museum read “Basta la Guerra, que llegue la paz” [“stop the war, let’s have peace”].

These read like calls to everyone and no-one in particular, an attempt to be physically seen and a desire to clear the view for Mexican citizens to see for themselves where they country is heading, and how they can help change its course.

Leave a Reply