Public Intellectual, Immigrant, Activist: the many lives of Stuart Hall Reflections

Arts & Culture, New in Ceasefire, Reflections - Posted on Wednesday, July 10, 2013 0:00 - 7 Comments

John Akomfrah’s The Unfinished Conversation “examines the nature of the visual as triggered across the individual’s memory landscape, with particular reference to identity and race. In it, academic Stuart Hall’s memories and personal archives are extracted and relocated in an imagined and different time, reflecting the questionable nature of memory itself. “(Liverpool Biennial 2012).

The Unfinished Conversation is, essentially, about a journey, or many overlapping journeys, to commitment, and a journey through difference: of class, race, and ethnicity. It is about the dialogue between displacement and belonging, of an individual, and also of a generation; the transformation of the diasporic migrant into a black British identity. It is also about the encounter with closures, essences and fixities and their gradual opening up and coming apart; the route to agency and identity, neither of which are ever settled.

In fact, ‘unsettling’ is a key characteristic of the film, both at the level of form and content. The triptych, split screen structures unsettles and destabilises our look, interrupts from the outset any notion of a singular personality or coherent narrative, and presents us with multiple voices, images, signs and sites as well as complex time frames. The triple screen also enacts the multi-accented life of Stuart Hall as academic, immigrant, and activist in (though not always of) the world he inhabits. We also see his involvement in one of the major and long lasting initiatives of the Left – the transmutation of the Universities and Left Review into the New Left Review in 1960, with Hall as editor.

As a kind of biography of a public intellectual, the film reflects Hall’s use of autobiography in the 1980s and 1990s as a strategy for theorising identity as a de-centred concept – always under construction. He said that ‘paradoxically, speaking autobiographically’ allows him ‘not to be authoritative’ (quoted in James Procter, Stuart Hall, 2004). Experience per se is of no value unless critically reflected upon and, at several points in the film, reference is made to Hall’s family which he described as ‘a lower middle class family that was trying to be an upper middle class family trying to be an English Victorian family’, thereby introducing the complex and conflicted at the level of the personal, and pointing up the prominence of class in his early theoretical formation – the readings from Woolf and Peake are neat counterpoints to this.

Not only Hall, but Cultural Studies also was formed at the extended moment of decolonisation (1948-1979) – a moment when imperial power began to unravel and, with it, its presumptions, modes of understanding, and violent practices. It is a conjuncture when critique and challenge, resistances, take on new shapes partly under the influence of anti-colonial struggles and the beginnings of anti-racist activity, large scale demonstrations against the US presence in Vietnam, civil rights struggles, all of which feature in the film.

It is also a moment when class – the working class – could still be linked to industrialisation, hence the images of manufacturing industry. It is the end of an era and the beginning of another with a very different set of configurations – but the film ends there at 1968. This new set of configurations required new theoretical frameworks and these came from a range of continental theorists in the 1970s and 1980s, mainly of a Marxist or quasi-Marxist nature, liberated from the thrall of Stalinism after Hungary 1956, and with primacy given to the culture, ideology, language and the symbolic rather than the solely economic. History and context have always been crucial for Cultural Studies and the film carefully places Hall’s personal, intellectual and political formations in their specific moments of emergence.

It would be erroneous to simply read off Hall’s ideas from his autobiography but, as the film shows, he originated in a context of what Grayson Perry calls the ‘vanity of small differences’ of identity, with gradations of colour operating as codes for class preoccupations which would help to formulate his own ideas of class and race when he emerged from the colonial fantasy of Jamaica to encounter the class politics of Oxford.

Central to all Hall’s thinking is the relation between culture and power and the issue of representation in all senses of the word. Like so many other major figures in the field, Hall’s migrant/outsider status (married to a white woman when miscegenation was still a source of outrage to many) gave him a critical perspective not always available to those of us immersed in the dominant culture from birth. His ways of seeing were simultaneously colonial and postcolonial. One of his most important contributions to Cultural Studies is anti-essentialism, the destabilising of ideas of fixity in identity and in thought.

As an intellectual his principal concern is with meaning as multi-accented, resistant to closures of any kind, and the contestation of meanings, the unsettling of orthodoxies, canons, and authorities of power. Gramsci’s complex idea of hegemony and Althusser’s concept of ideology were formative in this respect, providing the theoretical resources, in the early 1970s, for understanding the ways in which dimensions of power are carried in culture. The importance of popular culture, images of which are threaded through the film, has always been central to Hall’s thinking as they are a crucial part of the everyday life and meaning of a society, more complex and ambiguous than was realised in elite institutions.

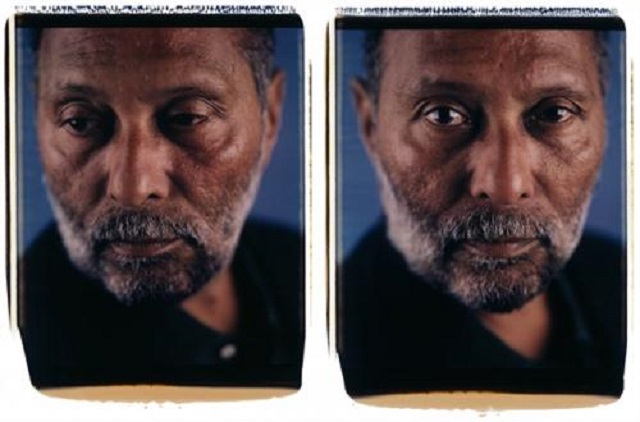

Dawoud Bey, Stuart Hall, 1998 (source: thenewartexchange.org.uk)

The film works collaboratively with its subject and with its images and sounds, and collaborative research was very much at the heart of the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) and Hall’s teaching and scholarship. This collaborative effect also enacts/replicates the interactive relationship between theory and activism, each impacting upon the other dialogically. The film is both collage and dialogue, multi-accented and multicultural. The activism was not just in action as a speaker at rallies but also became part of his academic life, in a sense, when in 1979 he left CCCS to become Professor of Sociology at the OU because, he said, of ‘[of] that more open, interdisciplinary, unconventional setting…of talking to ordinary people, to women and black students in a non-academic setting…it served some of my political aspirations’ (Procter).

What we see in the film is the emergence of both an organic intellectual and a black radical activist by 1968, with ‘black’ no longer simply being seen as a signifier of colour and race but as an articulation of a political stance, of difference and diversity not as items of policy but of political resistance, particularly as embodied in the second generation of diasporic migrants (this is clearly enunciated in a late 1980s essay, ‘New Ethnicities’).

The organic intellectual, Hall claims, ‘must work on two fronts at one and the same time. On the one hand, at the forefront of intellectual theoretical work…but the second aspect is just as crucial: that the organic intellectual cannot absolve himself or herself from the responsibility of transmitting those ideas, that knowledge…to those who do not belong professionally in the intellectual class’ (Procter: 50). This definition, incidentally, enabled him to understand precisely what Thatcherism succeeded in doing, hence his characterisation of it as ‘authoritarian populism’ as opposed to the national-popular concepts of Gramsci. The collective enterprise which became Policing the Crisis (1979), on the politics of ‘mugging’, was the outcome of work being done by community activists who were also engaged with the work of CCCS.

We see a number of shots of Hall on television in the late 1950s and 1960s (which I didn’t know about) which emphasised how this experience helped to shape one of his most important theoretical legacies: Encoding and Decoding in the television discourse. Forty years later, this may now seem obvious but this is because the analysis has entered academic common sense about the relationship in messages between sender and receiver; the idea that all media messages are complex and multi-accented, that however much investment goes into the production of meaning, its reading cannot be guaranteed. He outlined four levels of decoding: the dominant, the professional, the negotiated, and the oppositional.

It is with the oppositional that Hall is identified with in the film, itself a tribute by a major black film-maker who acknowledges his indebtedness to Hall. From the early 1980s onwards, a number of visual artists, photographers and film-makers have talked of the deep influence of Hall’s ideas on their work. The Unfinished Conversation is an Autograph ABP commission. Autograph ABP was launched at the Photographers Gallery, London in 1988 and Hall has played a seminal role in the conceptual and theoretical development of the organisation’s visual work. His critical writing and political vision (the politics of identity, perhaps most notably) continues to be a source of influence to generations of photographic artists who are interested in cultural difference (as a positive), displacement, and questions of race and history.

According to the producers, the project is designed to ‘examine the nature of the Visual in Western thought through the prism of Stuart Hall’s academic work on race, identity and photography’. I have concentrated on the ideas generated in, and by, the film; only by watching it carefully can we come to understand the complex ways in which the visual is articulated with the personal and political dimensions of one of the very few public intellectuals of our time, now 81 years old and sadly unwell but still very much under construction (‘I don’t belong anywhere any more’, he says at one point in Akomfrah’s film) as Mike Dibb’s wonderful four hour film, The Long Conversation (2009) indicates. In this film, we see Hall still at his charismatic best, engaging, witty, self-deprecating, reminding those of us who work in the field of his inestimable influence.

The Unfinished Conversation can be seen at the New Art Exchange on Gregory Boulevard, Nottingham, UK until the 14th of July. For details, click here.

7 Comments

Public intellectual, Immigrant, Activist: the many lives of Stuart Hall | Research Material

Public Intellectual, Immigrant, Activist: the m...

[…] In his latest column, Roger Bromley pays tribute to Stuart Hall, one of Britain's greatest living public intellectuals, on the occasion of the release of 'The Unfinished Conversation', an exhibition celebrating the enormous, enduring influence of… […]

Stuart Hall… | quartierslibres

Wednesday Links! | Gerry Canavan

[…] * And rest in peace, Shirley Temple and Stuart Hall. […]

Stuart Hall obituaries and tributes | Progressive Geographies

[…] His last editorial for Soundings is available here. Tendance Coatesy has a piece here. Birkbeck Psychosocial Studies have a tribute; and Gary Younge has a piece here. Hatful of History has a long excerpt from an unpublished piece discussing his work. Though written before his death, there is a good overview of his career and work by Roger Blomley at Ceasefire. […]

Friday Top Five – Feb. 14th | Project Africa @ The New School

[…] a little bit more biography check out this interview from 2007 by Tim Adams. You can also read this obit penned by Roger Bromley in […]

[…] McKenzie Wark via Greg Seigworth On a new doco about Stuart Hall. via Facebook https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/public-intellectual-immigrant-activist-lives-stuart-hall/ […]