The Tasmanian Aborigines Ghosts of History

Columns, Ghosts of History, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Wednesday, September 3, 2014 0:00 - 2 Comments

By Xain Storey

In this series, I will attempt to elucidate events in the past that are either ignored or suppressed by governments, education systems and mainstream media in the West. In particular, my focus will be on colonialism, with reference to specific large-scale affairs involving plunder, exploitation and destruction, that have left ineffaceable scars on nations around the world today, scars that indigenous populations still feel to this day.

“In order to have hope for the future, and for the nation to have maturity & strength, there has to be justice for the past.” – Sally Morgan

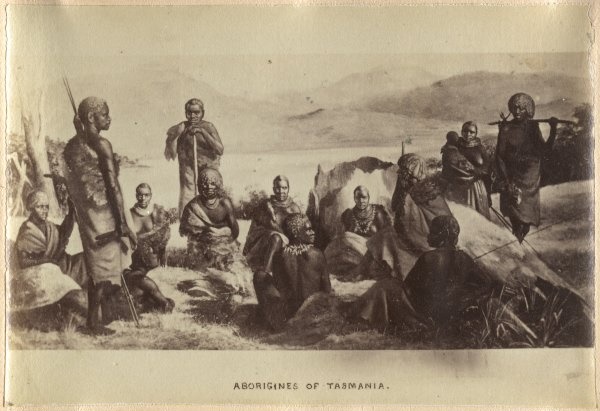

The first Aboriginals of Tasmania are thought to have reached their eventual homeland from Southern Australia, across a glacial land bridge that formed in the Bass Strait due to the Ice Age, in the late Pleistocene, around 40,000 years ago. From then on, the Aborigines (or Palawa) remained there (due to sea levels rising again to flood the land bridge, preventing any travel between Australia and Tasmania) , largely undisturbed, until the arrival of the British in 1803.

It is worth noting that, before 1803, other Europeans made contact with the natives there. In 1642, Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman journeyed to what he called ‘Van Diemen’s Land’ (which was legally changed to ‘Tasmania’ in 1856). However, Tasman did not come into contact with any Aboriginals, who called their land ‘Trouwunna’ or, as the reconstructed Palawa Kani language translates it, ‘Lutriwita’ . Captain James Cook named Van Diemen’s Land a British penal colony in 1788, which was a result of an endeavour to replace settlements lost due to American Independence.

In 1803, John Bowen of the Royal Navy journeyed to Risdon Cove to establish a penal colony, due to fears that the French (who had also reached the region) would lay claim to Tasmania. Upon British arrival, there was an estimated population of 5,000 – 7,000 indigenes divided into over 50 clans. However, historian James Bonwick, who lived in Tasmania from 1841, noted, “Mr. Robert Clark in a letter to me, said : ‘I have gleaned from some of the aborigines, now in their graves, that they were more numerous than the white people were aware of, but their numbers were very much thinned by a sudden attack of disease which was general among the entire population previous to the arrival of the English, entire tribes of natives having been swept off in the course of one or two days’ illness.”

Economic and social affrays began soon after the invaders arrived, as the British food supplies were not able to meet the nutritional needs of the settlers. Grain and salted meat supplies from Britain and other colonies were scarce and, when they did arrive, they were water damaged, infested with weevils or were completely inedible. This led to serious illness amongst the settlers in the winter of 1803-1804, prompting them to hunt for food endemic to Van Diemen’s Land, such as kangaroos, wallabies and emus. Though this saved many of the colonists’ lives, it significantly reduced the island’s animal population, resulting in serious tensions between the invaders and the natives.

The colonists brought British families, convicts (who were either used as servants to manage pastoral settlements, or escaped and became sealers or bushrangers) and soldiers to Tasmania, with their numbers increasing every year. Invaders monopolised whaling and sealing industries, establishing timber industries which further compounded the socioeconomic conditions of the Palawa. From 1809, the settlers began killing Aboriginal parents and abducting their children, using them as domestic slaves, forcing them to assimilate into their communities, and erasing their Aboriginal connections. Due to the relative scarcity of British women, sealers and other invaders abducted and raped Palawa women, enslaving and trafficking them. Chief Protector of Aborigines, George Augustus Robinson, commented on the sealers’ treatment of Aboriginal women as, “the African Slave Trade in miniature”.

From 1826, following rapid pastoral expansion, the Aboriginals were pushed further away from their homes, and British settlers occupied the heartland of Van Diemen’s Land. This fomented discontent amongst the natives, culminating in armed resistance against the settlers. Robinson echoed Chief Tongerlongter of the Oyster Bay tribe, writing that:

“(T)he reason for their outrages upon the white inhabitants was that they and their forefathers had been cruelly abused, that their country had been taken away from them, their wives and daughters had been violated and taken away, and that they had experienced a multitude of wrongs from a variety of sources.”

The Palawa sought justice for their stolen land and for their people being killed, enslaved, abducted and forced to adhere to the exploitative politico-economic system of the Tasmanian colony. The Aborigines waged guerrilla warfare, which was followed by a rise in racist sentiment amongst the colonists, many of whom argued for hanging natives to ensure a “conciliatory line of conduct”. In 1826, the Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser published an article advocating that, either the ‘Aborigines’ be removed from the colony, or “hunted down like wild beasts and destroyed.”

In late 1828, due to intensifying violence between settlers and Aboriginals, Governor Arthur declared martial law. This period was the start of what quickly became known as the ‘Black War’. Indigenous dissidence was labelled an act of war against the King, thus giving a governmental imprimatur for the slaughter of Aboriginals. The government offered a bounty of £5 for each adult and £2 for every child captured. The military were given authority to kill any native who resisted, though in practice many Palawa were shot, irrespective of whether they showed signs of violence.

The “Black Line” is the name referring to the (detrimental but unsuccessful) attempt to forcibly transfer the Palawa to the Tasman Peninsula, undertaken by around 2,200 colonists – including the military, convicts and police. In 1830, the Colonial Times wrote, “Settlers … consider the men as wild beasts whom it is praiseworthy to hunt down and destroy, and the women fit only to be used for the worst purposes. The shooting of blacks is spoken of as a matter of levity.”

Though the resistance was extremely troublesome for the invaders, it faded by 1832 due to the genocide of between 1000 and 2000 Aborigines (likely more in light of the lack of death toll records for the natives). Their decreasing numbers led to surrender in 1833, after they were persuaded by Robinson who had also been relocating natives to Flinders Island, via pressurised migration and forced removal, since 1829.

By 1835, Robinson reported to Arthur that, “The entire Aboriginal population are now removed (to Flinders Island)” , which constituted around 300 at the time, compared to over 1,500 in 1824. The natives were forced into exile at Wybalenna camp, away from the mainland, where they were exposed to institutionalised malnutrition, introduced disease, inadequate clothing in freezing weather, vermin-infested, damp huts to sleep in, a lack of fresh food and water and abuse by convicts. Most of them died of respiratory diseases due to the dearth of medical care. By 1847, only 45 survived, and were transferred to an abandoned army camp in Oyster Cove on mainland Tasmania, where the living conditions were no better. By 1876, all the Palawa people had died, apart from a woman named Fanny Cochrane Smith, recognised as the last full-blooded Palawa, who passed away in 1905.

Today, mixed Tasmanians of Palawa descent seek redress for their erased history – their language, their culture and people – their stolen generations and colonised homelands. The Tasmanian Aborigines suffer from disproportionate rates of poverty and thus an array of health problems (both mental and physical). Aboriginal youth suffer the highest suicide rates in the world, while mortality rates for infants and young children are 2-3 times higher than those for non-Aboriginals.

Most aboriginals live in highly damaging socioeconomic environments, because of the abject inequality – political, racial and economic – that has been carried over since the systematic, geographic, psychosocial and cultural genocide of the Tasmanian Aborigines and the eradication of the foundations of their communal life. Though much time has passed since the genocide, it would be a callow notion to suggest that the present-day plight of the Palawa is unrelated to their past.

This is something the world needs to know. It needs to know what happened, and it needs to know why it happened.

“… colonialism cannot be left without blame.” – Raphaël Lemkin

2 Comments

Dutch king continued slave trade after official ban | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Sonia

Now I know where I get my fight from…thanks to my Chief Warrior Tongerlongter!

[…] Ghosts of History | The Tasmanian Aborigines […]