The Politics of Misrecognition: on Mona Eltahawy’s ‘Why Do They Hate Us’ Sister Outsider

New in Ceasefire, Sister Outsider - Posted on Sunday, May 6, 2012 0:00 - 5 Comments

By Hana Riaz

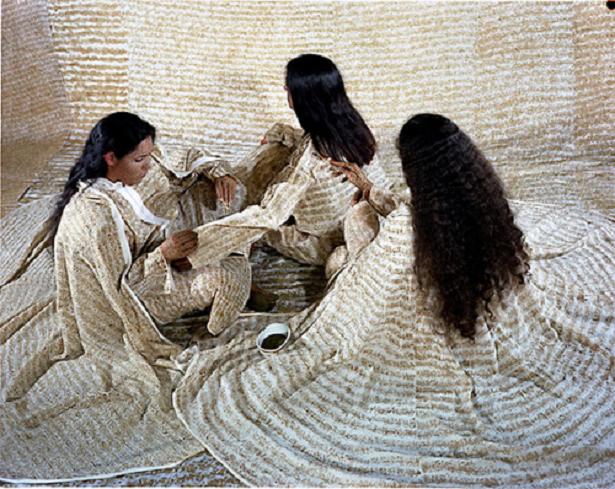

‘Converging territories’ by Laila Essaydi

“I do not want to be tolerated, or misnamed. I want to be recognized.”

— Audre Lorde

The problem with any –ism is that it splits you. It leaves you a division or shadow of who or what you really are. What remains are traces: aspects of your narrative, distortions in how they are told, and parts of yourself that you have to simply give up or leave at the front door– there is no room for all of you here. In this realm, even in spaces of ‘social justice’ or ‘activism’, the choice is limited: resign yourself to being non-existent or present halves, maybe thirds or quarters or eighths of yourself.

Mona Eltahawy’s piece ‘Why Do They Hate Us’ in Foreign Policy’s recent ‘Sex’ issue (that alone warrants approaching it with trigger caution) caused a stir across the blogosphere. The real war on women, she proclaims, is in the Middle East. She sites some pretty indisputable examples and accounts of the endemic sexism that is definitive of Arab and Muslim women’s lives: female genital mutilation, child marriage, sexual harassment, exclusion from the labour market, and low literacy rates.

For her, the hatred these barbaric, backward and savage Muslim (or ‘Islamist’) men have for women is a consequence of a toxic culture and, mostly, religion– the “worship of a misogynistic God” and the following of a Prophet Muhammad who, like all these men now do, married a “child”.The Arab Spring thus becomes devoid of meaning, the real fight is a fight for women, and the real oppressors are in Egyptian homes and bedrooms, not solely in that palace.

“Resist cultural relativism”! She cries to an American audience, “we are more than our headscarves and our hymens… listen to those of us fighting”. Ironic it is that she reduces the ‘us’ to just that.

While it is important to talk about and make known the plight of the women she attempts to speak on behalf of, few would hesitate to argue that her telling was reductive. She presents these women without agency by not only speaking for them, but by depicting them as perpetual victims – of men, of religion and even of the revolutions they were so crucially a part of. She asks her American audience to amplify the voices of resistance yet offers virtually none.

While it is important to talk about and make known the plight of the women she attempts to speak on behalf of, few would hesitate to argue that her telling was reductive. She presents these women without agency by not only speaking for them, but by depicting them as perpetual victims – of men, of religion and even of the revolutions they were so crucially a part of. She asks her American audience to amplify the voices of resistance yet offers virtually none.

But what is it about these reductions, these tropes and these stereotypes she plays into that makes her piece so alarmingly dangerous?

Frantz Fanon, in Black Skin White Masks (1967), used psychoanalytic theory to explain racism within a colonial context. He argued that racial stereotyping or the ‘white gaze’ gave way to a split subject and division of self. The black person would be resigned to a perpetual misrecognition, a kind of racist violence that is born from the refusal of the white ‘other’ to acknowledge the black person.

Recognition of course was recognition of black humanity, of the black individual to be acknowledged in their entirety. For Fanon that colonial, white ‘othering’ gaze fixed him as an object; it denied him who he was and who he wanted to be; a split he felt would never heal.

Liberal identity politics often attempts to frame people. Whilst it doesn’t always lock them into stereotypes, more often than not it forces people to choose between parts of themselves, parts of their homes, parts of their communities, parts of their daily experiences, and ultimately parts of their struggles. Mona failed to conceive of these women as resisters in their own right, women who struggle and fight and challenge, just as they may be victims in ways that aren’t necessarily always accounted for.

More importantly, she also failed to conceive of them as living human beings. Women who belong to multiple communities – whose identities aren’t just defined by the category ‘woman’ even though it may be definitive of a large proportion of their material reality. The same women that may be gay, straight, trans- or cis-gendered; they may be poor, middle class, or part of the elite; young or old, with families or none; that interact and live with and love all types of men and women; that are effected by war, imperialism and dictatorships, just as they may be targets of ‘democracy’.

These are the same women that may or may not work; that span across abilities; that are citizens, and noncitizens of nation-states; that live in rural or urban areas; that have access to a plethora of resources or at times none; the very same women that belong to faith communities that they may not want to dispose of (which, ironically, doesn’t solely apply to Islamic ones); that may or may not be literate; they may be teachers, activists, writers, and/or a bunch of other things most likely all at once. They may defy none, some or all binaries presupposed in this paragraph.

These are the same women that may or may not work; that span across abilities; that are citizens, and noncitizens of nation-states; that live in rural or urban areas; that have access to a plethora of resources or at times none; the very same women that belong to faith communities that they may not want to dispose of (which, ironically, doesn’t solely apply to Islamic ones); that may or may not be literate; they may be teachers, activists, writers, and/or a bunch of other things most likely all at once. They may defy none, some or all binaries presupposed in this paragraph.

These are the same women whose lives are real and lived, whose experiences shape and affect their identities and who they are. These are the same women who, like the global majority, are subject to one or more systems of domination. They shouldn’t have to choose between their liberation struggles, let alone be told who they are and how to fight them.

It’s no wonder her article was received by Muslim and Arab women with angst and fury, the same women that have provided necessary responses to counterbalance her self-appointed position as representative of all Egyptian/Arab/Muslim women to the West.

Fanon and Lorde importantly remind us that the fight against any oppression is really and truly a struggle for humanity. Black and other women of colour feminists all over the world call for a politics that takes account of people in their entirety, one that acknowledges the intersectional realities that we all live precisely because we create and negotiate out of them.

Part of being a feminist or an ally requires us to understand just that, that the work we do comes from a deeply personal place and that this fight is perhaps most effective when we recognise that this battle can only be won by representing ourselves honestly.

Perhaps Mona’s piece would have been better received if she had said just that: “this is who I am and this is what I believe”. Had she done so, she would have avoided the trap of a politics of misrecognition that women of colour no longer accept, especially when delivered by liberal feminists.

5 Comments

Teodora

I have found most responses to Mona’s problematic article just as, if not more, problematic. OK she doesn’t represent ALL Muslim, Arab women, and genital mutilation is just as much of a Christian problem as it is a Muslim problem in the countries where it continues to be practiced, for example Nigeria (not in the Arab world), therefore such misogynist practices are not easily reducible to a single religion or culture. However, to point out the vast diversity that exists in the Arab world, as everywhere else, does not dissolve the fact that misogynist practices do exist in patriarchal cultures, everywhere and in different guises. Such horrific violence does need to be dealt with and pretending otherwise is complicity with the very systems that make possible violence against women, in whatever form it takes. My criticisms do not refer to your article entirely, and you make very good points, but the vast majority of responses I’ve read do not go far enough in providing the complexity they seek to. The best response to Mona I’ve found so far is by Sara Mourad http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/5355/politics-at-the-tip-of-the-clitoris_why-in-fact-do. From her I took that the answer to simplistic (mis)representations of the Arab world is to highlight the interplay of the multiplicity of hierarchical and oppressive power structures operating at this point in time, rather than to downplay the severity of the one form of oppression that got flagged up with equally simplistic rhetoric about diversity. Yes, women are all different but then oppression and subjugation also take different forms. The task is to expose and challenge oppression in as a nuanced form as possible rather then to exclaim “Talking about Arab women’s rights is racist” just because it got published in a white Western publication with shit editorial practices. To conclude, I am just making general observations about what I’ve read so far and have experienced as deeply problematic. Your article is on the whole very good and I look forward to reading more of your columns.

Bobby

Great article Hana!

@craig: “IMHO all religion is toxic because it prescribes a synthetic way of thinking, and negates the act of thinking for oneself.” – I see your rhetoric as exactly what this piece is negating. Surely the tendency to be so definitive about religion is almost… religious?

[…] the full article here Share this:ShareFacebookTwitterTumblrEmailPrintLike this:LikeBe the first to like this post. […]

bitterkomix

Lovely commentary Hana Riaz! Thank you. Aside from the plurality of identities and perspectives, there are also a plurality of religious contexts and institutions. I like that you cited Nigeria, because this is an excellent example of the many different strands of religion, sexism and feminism. You might want to check out the Nigerian scholar, Hussaina Abdullah on this (see her text from Mamdani’s edited volume “Beyond Rights Talk and Culture Talk”). There’s an interesting tension between some of the feminist organisations and their indirect support for patriarchal institutions in Nigeria. In some ways, Eltahawy’s piece reminded me of this tension, in that it completely ignores the rich history of female Muslim leaders and thinkers, and indeed, of feminism. A nice micro-example is the Alhazai of Maradi, a revered and powerful merchant/scholar class from Maradi (now in Niger) who were composed of both women and men in the 19th century. Or there was the truly inspiring civil rights work of the deeply religious intellectual and activist Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, who was executed for apostasy in Sudan in 1985. I find it remarkable that no one asks why the call for civil rights is often rejected by both women and men, or how and why dictators quash or co-opt civil rights movements.

The refusal to acknowledge the historical trajectory of patriarchy (which seems to have strengthened itself in a number of regions over the last century) and its political and economic institutional foundations is deeply worrying.

Interesting article, but I disagree that if Mona Eltahawy had stuck to first person opinions about secular feminist ideology it would have sat better with Muslim women. IMHO all religion is toxic because it prescribes a synthetic way of thinking, and negates the act of thinking for oneself. So dealing logically with complex issues of race and sex, representation and revolution all become meaningless when the answer all boils down to the authority of a bearded, supernatural, magical entity that lives in the clouds and controls all our destinies. All religion, yes buddhists you too.