For the Many: How Labour’s 2017 General Election Manifesto changed everything Analysis

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Monday, August 6, 2018 14:59 - 0 Comments

By Mike Phipps

While some general election results, like 1970 and 1992, are surprising, 2017 was genuinely astonishing. Labour’s result did not just defy all media expectations and assumptions, it reduced Theresa May’s Conservative Government to a minority administration. Labour won over 12 million votes, a 40% share of the vote — 10% up on Ed Miliband’s score in 2015 and higher than any in the last forty years, except Blair’s two landslide victories.

Jon Snow confessed live on Channel 4 News: “I know nothing. We, the media, the pundits, the experts know nothing. We simply didn’t spot it.” This was perhaps the starkest, although by no means last, admission of failure from commentators and politicians alike.

Precisely why they got it so wrong needs detailed analysis, but the degree of groupthink involved and the convergence between supposedly impartial media outlets, Conservative-supporting newspapers and much of the political class exposed systemic failings in the coverage of the 2017 general election.

The dismissive approach to Corbyn by overtly Conservative outlets is perhaps more understandable than that of newspapers like The Guardian, which prides itself on its understanding of, and connection to, the inner life of the Labour Party. Evidently, it failed to learn much from its misreading of the two leadership campaigns that Corbyn won in 2015 and 2016.

Lazy narratives about populism, whether of left or right, substituted for serious analysis. But centrist populism can be just as authoritarian, as the post-election trajectory of French President Macron indicates. Blair was populist too in his day, railing against the forces of conservatism, cashing in on fashions for rebranding and technocratic managerialism, celebrating all things new and basking in the inevitability of globalisation, the end of ideology and the triumph of an eclectic postmodernist pragmatism.

Compared to this hubris, Corbyn’s campaign was less about a populist disruption of the political system than a popular left wing programme that was rooted firmly within its framework. The second lazy narrative was that this was a re-run of Labour’s historic defeat in 1983. Michael Foot had been labelled Worzel Gummidge in the media in that election. Boris Johnson attempted to reprise the theme in 2017 by calling Jeremy Corbyn a mugwump. Corbyn was a throwback, a figure of fun, a loser. Only as the Conservative campaign began to unravel, thanks to a robotic, un-empathetic leader and a bleak manifesto that contained nothing for young people and the so-called ‘dementia tax’ for the elderly, did the mainstream media begin to suspect they might have got it wrong.

Could a leftwing leader win? Surely the received wisdom of the last forty years, a lesson drummed home by Labour’s 1983 landslide defeat, and by New Labour spin doctors ever after, was that Labour could win elections only from the centre?

That might have been true once. But all the evidence on the failure of centrism in recent years was available to anyone with enough curiosity to look. It even had a name: Pasokification, coined by James Doran to describe the electoral and organisational meltdown of democratic socialist parties. This was already occurring in Miliband’s Labour Party. The collapse of Labour in Scotland in the 2015 general election from majority party to having just one seat was the most spectacular expression of this phenomenon.

More importantly, it did not happen because Labour was too leftwing — a trope large numbers of moderate Labour MPs lined up to disseminate immediately after the 2015 election. In Scotland, the evidence was irrefutable: Labour had been outflanked from the left by the SNP’s socially progressive agenda. Corbyn’s success in the 2015 Labour leadership election was a recognition by Party members of this reality. A retreat to Blairite centrism would only accelerate the trend towards oblivion: something new was needed.

This understanding was prescient. The decay of traditional socialist parties across Europe as they struggle to adapt to this new reality is now highly visible. Last year, both the Dutch and French Socialist Parties were dissolved, with the latter getting just 6% in that year’s presidential and 7% in the parliamentary elections. Similarly, the Irish Labour Party got its worst result in history after joining an austerity coalition government in 2016.

Although this crisis may have only recently become apparent, these processes have been gestating over a long period. Tony Benn in his day understood this trajectory and frequently referred to a crisis of political representation, given the similarity of the three main parties advocating first neoliberalism, and then austerity, even though these policies were not widely supported by the public. Privatisation especially, and privatisation of rail and of parts of the NHS in particular, was often pushed through in the teeth of public opposition.

The evidence for this disconnect between politicians and voters was palpable in the 2001 general election, when voter turnout fell to 59%, an eighty-year low, and again in 2005, when it hit 61%. Until then, electoral turnout in all post-war general elections had never fallen below 70%.

Not only was there no electoral expression for alternative viewpoints, they were scarcely covered in the media. Even after his election as leader in 2015, an estimated 60% of ‘hard news’ stories about Jeremy Corbyn in his first week were negative, compared to only 6% that were positive. Only in the general election campaign itself, when legal rules about balance were more strictly applied, did this begin to change – which helps explain why Labour could move from being around twenty points behind the Conservatives in the opinion polls at the start of the campaign to being eight points ahead of them a few days after it was over.

The Economist argued in a piece entitled “Jeremy Corbyn, entrepreneur”, that Clayton Christiensen’s economic theory of disruptive innovation helps explain Corbyn’s unexpected election result in 2017. In this model, the most interesting businesses start life on the margins. They succeed by spotting under-served markets and inventing ways of reaching them…But as they improve their products they end up revolutionising their markets and humbling yesterday’s incumbents…According to this vision, Jeremy Corbyn’s spent 30 years on the margins of British political life…until he spotted the biggest under-served market in British politics – the young – and provided it with what it wanted: the promise of a new kind of politics.

There is no doubt that young people in recent years have been politically “under-served” – “abysmally treated by the British establishment,” in The Economist’s words, whether over student fees, house-price inflation or insecure and exploitative employment opportunities. Jeremy Corbyn certainly won the youth vote, leading the Conservatives by 47 percentage points among 18 and 19 year olds. Furthermore, the enthusiasm generated by this orientation, the impact on social media and the increase in electoral turnout (especially in this demographic) to the highest in any general election in twenty years, helped redraw the electoral map. This achievement unites Corbyn’s campaign with left populist movements, like Podemos in Spain, whose slogan in the 2014 EU elections, “When was the last time you were excited about voting?”, could have been tailor-made for Labour’s 2017 general election campaign.

Unlike Podemos, however, the ideological origins of the Corbyn phenomenon were rooted in one of Britain’s establishment parties. Some see Corbyn as the natural heir to Bennism, the leftwing movement of the late 1970s and early 1980s that reached its zenith in Tony Benn’s narrow defeat in Labour’s 1981 deputy leadership contest. But this is to neglect the fact that Benn’s policies, such as the Alternative Economic Strategy, were specific to a very different time, when Britain’s manufacturing base and industrial working class had not yet been dismantled.

In fact, the key to understanding Corbynism lies in recognising that it combines much more long-standing democratic socialist values with an inclusive and unifying approach to political practice. Much of this praxis was hidden from view during the long decades of the neoliberal consensus, but there were always alternative roads that could have been taken. The 1984-5 miners strike was a pivotal turning point, not just because of its potential to defeat and even bring down the Thatcher Government – indeed, the miners’ defeat definitively ensured the hobbling of the trade unions and set Labour on a path of embracing Thatcher’s legacy – but also because the vast scale and variety of supportive action highlighted an alternative vision of class and community solidarity.

Many on the left emphasise the continuity of Corbyn with Bennism, the old left and roads not taken. But there is also something post-political about Corbyn that transcends left and right ideology, offering practical solutions to the new problems in the age of austerity. Indeed, ‘common sense’ is the term repeatedly identified with Labour’s 2017 manifesto, both by unequivocal supporters, such as Chris Williamson MP and critics like Tom Gann. Owen Jones too called it a “moderate common sense set of antidotes to the big problems”.

This reclamation of ‘common sense’ by the left is of considerable significance. Stuart Hall and Alan O’Shea have argued that “the battle over what constitutes common sense is a key area of political contestation.” For many years, the market was the cornerstone of what constituted ‘common sense’.

But popular common sense also contains critical or utopian elements. For example, there is a widespread sense of unfairness and injustice about ‘how the world works’ – landlords exploit tenants; banks responsible for the credit crunch expect to be bailed out by taxpayers; CEOs receive immense bonuses even when their companies perform badly; profitable businesses avoid paying tax; and companies do not pass on to consumers the gains from falling commodity prices.

The idea of clinging to such iniquities, and indeed the entire framework of neoliberalism, appears increasingly devoid of ‘common sense’ and driven by ideological conviction, given the manifest failure of austerity and market-driven solutions to the crisis over the last decade. For Jeremy Gilbert, the 2017 general election was a historic turning point: “neoliberalism no longer presents itself as an unchallengeable common sense, defining a political terrain from which nobody can depart for any distance.”

But if common sense provided a basis for neoliberalism to become so dominant pre-crisis, the loss of that status presents socialists with new opportunities. The Labour MP Chris Williamson is surely right to argue that the left’s embrace of this term opens the way for an era of socialist hegemony.

The ‘common sense’ solutions to the social problems addressed are necessarily radical, because the problems of housing, debt, public health and education, environmental degradation, exploitation at work and many other areas are greater than ever. They are especially intense for young people, for young graduates who were led to expect better, as Paul Mason has argued in Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere (Verso, 2011), but also for public sector workers, benefit claimants, frequent NHS users and many other people not identified in the aforementioned Economist article.

Those taken aback by the 2017 election result also failed to see that Labour’s new members, who have nearly trebled in number since the Party’s 2015 election defeat, together with their money and enthusiasm, would necessarily entail a changed relationship with voters, if only in the amount of door-to-door voter contact Labour could undertake in 2017. The media seemed collectively to accept that appealing to activists must inevitably alienate the masses – as though the expelled Marxist sects of the 1980s had somehow octupled in number in the intervening years – in fact, for a variety of reasons they went into steep decline – and were waiting in the wings to take over the party.

Of course, there were many leftwing activists alienated by New Labour who were drawn back ideologically by Corbyn’s ascent, from the Greens in particular. But this does not begin to explain the whole phenomenon. Many of the new intake were wholly new to formal political activity, like the canvasser in the marginal constituency of Hampstead and Kilburn whom I met on polling day, whose only previous experience of campaigning was donning a Corbyn t-shirt and starting random conversations with people on London’s vast public transport network about the leader’s ideas.

Had the media bothered to investigate, they might have noticed the importance of social media in the campaign. This should not have taken anyone by surprise, given its critical role in both of Corbyn’s party leadership campaigns, as Alex Nunns details in The Candidate (OR Books, 2016). One video produced by Momentum, the organisation set up in 2015 to organise Corbyn supporters and drive forward his agenda, was viewed over 7.6 million times and reached 30% of British Facebook users.

One of the key features of the 2017 campaign was the huge number of rallies that Jeremy Corbyn personally addressed. This activity began long before the general election. Ever since becoming leader in 2015, Corbyn was spending as many as four days a week on the road, from Thursday to Sunday travelling around the country campaigning, sometimes in places that had never had a Labour leadership visit. In March 2016, he addressed a meeting of 1,500 people in Aberdare, a Welsh valleys town with a population of just over 30,000. Most of the media chose to ignore all this, conveniently packaging such unprecedented events into their ‘preaching to the choir’ narrative.

So prevalent was the myth that leftwing parties cannot be popular that politicians and media alike chose to ignore the evidence of their own eyes – Labour’s near trebling of its membership to over half a million, the huge leadership rallies, and even the shifting opinion polls – rather than recognise the reality. Jon Snow and others at least had the humility to recognise their collective blunder, albeit only after the election result had decisively buried the dominant narrative.

The 2017 election was a battle between two competing narratives – a stable government offering a competent Brexit versus an insurgent Opposition, committed to fighting austerity and overcoming the divisions of the 2016 Brexit referendum with a promise of unity and inclusivity. To many, it looked like fear versus hope. These sound like platitudes, but they have content. The referendum campaign a year earlier had seen the stabbing to death of a pro-EU Labour MP by a neo-Nazi, who, according to witnesses, shouted, “Put Britain first” as he carried out the act. Following the referendum, racist attacks rocketed – by over 50% in the immediate aftermath.

It was thanks in no small part to the way Labour fought the 2017 general election that only 6% of people surveyed felt that immigration was the most important factor determining their vote. This breaks down as 9% of Conservative and 3% of Labour voters, down from 47% and 28% respectively in the 2015 general election.

Corbyn’s narrative was unifying on other fronts. The Brexit referendum pitted ‘left behind’ rural areas against urban ‘metropolitan elites’. It divided people on generational and ethnic lines, creating conditions where Theresa May felt she could shamelessly pitch for the ‘patriotic working class’ vote. Faced with the inclusive themes of Corbyn’s campaign, however, this utterly failed to resonate with its intended audience.

The refusal of Corbyn to continue New Labour themes of demonising benefit claimants continued this unifying approach, ending the artificial division between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor, which Labour had helped perpetuate in the past. One of the factors that fuelled popular support for Corbyn in his 2015 Party leadership bid was the abject failure in the summer of that year by Labour MPs to vote against Conservative Government benefit cuts. Corbyn’s principled position on this was reflected in his campaign, which exposed the nonsense about ‘unworthy’ benefit recipients, by highlighting how much of the welfare bill goes towards subsidising the poverty pay of people already in work.

The Manifesto

All these themes were fleshed out in Labour’s election manifesto. But this, too, was pigeon-holed by many into the “appealing to the choir” narrative, not least The Guardian which opined that it was based on “Mr Corbyn’s preference for energising his own support rather than persuading those outside it.” This turned out to be a classic misreading. YouGov found that the manifesto was the main reason people gave for voting Labour. Newly elected MP Laura Pidcock, introducing Jeremy Corbyn at a rally in Carlisle some weeks after the election, described it as “unequivocal statement of hope.”

The Labour 2017 manifesto’s emphasis on ending austerity and supporting redistribution and public ownership was popular – in fact polling has shown re-nationalisation has been consistently favoured by most voters for several years, including during the 2015 election. There were plenty of other policies in the document that would appeal as well.

Those who worked on it were proud of the effect it had on the election campaign, in helping boost Labour’s vote, energising Labour Party members and engaging the public in a way that few manifestos ever have. It was written from scratch in the space of three weeks from when the election was called. This was a very challenging timeframe. Those involved estimate they averaged 80-100 hours per week to get it done.

The manifesto was drawn from papers written by the National Policy Forum (NPF), the labyrinthine process of policymaking developed in Labour’s years in opposition, when so-called ‘moderates’ in charge of the party decided that the best way to move the party rightwards was to replace the sovereign policy-making power of Labour’s annual conference with a new structure. These papers had themselves been based on the ‘ten pledges’ passed at Labour’s 2016 Conference following Jeremy Corbyn’s second leadership election, as well as two sets of policy documents from the two leadership elections in the last two years. There was a short manifesto consultation process which involved shadow cabinet members, the NPF and trade unions and party members via an online consultation.

The results of the online consultation helped prioritise the policy areas, but it was necessarily limited given the timeframe. “The party does not have a platform capable of involving members in the way that Podemos in Spain does,” one insider told me, “but this needs to happen: the NPF is structurally flawed and is not understood by 99% of members – and policy cannot only be made only once a year at an annual delegate conference.”

Different sections were written collaboratively by heads of policy in the Leader’s team, shadow cabinet members and the executive directors of policy. Almost immediately there were individual one-to-one meetings held with most of the shadow cabinet, and a consultative meeting of the NPF, all ahead of the drafting. Consultations on some specific issues carried on later into the process as policy was still being refined in some areas due to the unexpected snap election. The costings were continually prepared as policy was developed. “The decision to publish a costings document was taken quite early on in the campaign,” one source told me, “to demonstrate our economic credibility and as part of our more open approach to politics.”

For the many, not the few is an interesting title. It chimed with the theme of the local election campaign Labour had waged a month earlier. Conceptually, it sidesteps the slogan of the 99% versus the 1% of the Occupy movement and appears to speak of class interests while couching its message in populist language. The title was the same mantra articulated at declaration after declaration on an election night twenty years earlier that saw Tony Blair come to power with an unprecedented Labour majority.

But the content of the slogan had changed. Aspiration was still at the core but this was something that could only be achieved collectively. In contrast to the rampant individualism of earlier neoliberal projects, including that of Tony Blair, whose government promoted individual competition and cut social provision, Corbyn offered a very different vision. “We understand aspiration and we understand that it is only collectively that our aspirations can be realised,” he wrote in 2015. Insiders confirmed this. “We wanted to present a universalist and redistributionist vision to transform Britain for the many not the few,” one told me.

The 2017 manifesto was very different in content too. Firstly, it marked a return to traditional democratic socialist values of community, solidarity and social justice. Secondly, it was concrete. There were specific pledges that cut through the usual bland platitudes that have become the hallmark of election manifestos across parties. Even the section on foreign policy, as Glen Rangwala argues in his chapter in For the Many, had some very specific commitments about recognising Palestine and allowing the Chagos islanders to return to their homeland.

Thirdly, there was something to appeal to key sections of the electorate – the abolition of tuition fees, restoring the ‘triple lock’ on pensions, raising the minimum wage to £10 an hour – real commitments that might be expected to generate enthusiasm among those affected. These policies appealed not just to traditional Labour voters: there is evidence to suggest that Labour’s proposal to renationalise the railways and some utilities resonated among former UKIP and Conservative voters, as part of a narrative to take back control of Britain’s economy from the forces of globalisation.

These unifying themes appealed to voters. If the 2017 election was unusual in that large numbers of voters changed their views during the course of a short election campaign, Labour’s manifesto was one of the key reasons for their doing so. The jump in the opinion polls which Labour enjoyed suggests the document altered the course of the election.

But its appeal was not just to the electorate. The manifesto played an important role in overcoming the fractures within the Labour Party itself, not least among the parliamentary party, whose hostility to Corbyn was reflected in their overwhelming support for Owen Smith’s leadership challenge in 2016. “It was a manifesto I was proud to stand on,” said one Labour MP who voted for Smith in that leadership contest. “It really differentiated us from the Tories and it’s the first time I’ve felt that.”

Some have criticised the manifesto for being excessively responsive to single-issue campaigns and activist groups. But this again commits the error of seeing such groups as not only unrepresentative of, but counterposed to, the interests of the broader electorate. To accept this reasoning is to acquiesce to a New Right theory of such organisations as self-interested empire-builders, seeking more resources for their narrow agendas, divorced from the needs of a supposed silent majority. Tony Blair’s Government reacted to groups largely from this standpoint – even the trade unions, whose millions of members had been a financial, organisational and political mainstay for Labour in its wilderness years after 1979.

Jeremy Corbyn’s approach to campaigning groups was radically different. It was based on an understanding that such groups, in the context of an electoral crisis of representation, played a vital role in providing alternative channels of engagement that could find an expression in Labour. In opposition, the party had attempted this before, but the long track record of parliamentary support for organisations such as Disabled People Against Cuts on the part of Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, even if it meant breaking the New Labour whip, gave their approach much greater credibility,

The influence of Labour’s manifesto can be felt too in the debate that broke out within Conservative Party ranks immediately after election day. The issues raised by May’s critics – public sector funding, student fees, an easing of austerity, were all themes prioritised by Labour’s manifesto.

The manifesto’s impact may be even more far-reaching. Through its concrete radicalism, the manifesto helped widen the Overton window of what can be realistically discussed as potential public policy. If the common sense solutions to Britain’s problems are necessarily radical, then all kind of ideas previously dismissed as utopian become legitimate topics for debate: from universal basic income to a shorter working week and more leisure time, ideas explored at length in Rutger Bregman’s bestseller Utopia for Realists (Bloomsbury, 2017). But it’s not just the manifesto; it’s the belief that it will be implemented that counts. Belatedly, pundits are beginning to admire the ‘authenticity’ of Jeremy Corbyn.

This is not about ‘looking authentic’, it’s about being it, something better called integrity. In Corbyn’s case, this has been established over a lifetime of political activity. The hard-working backbench MP who never put promotion ahead of principle was the first ever to have a surprise party organised for him by no less a figure than the Speaker of the House of Commons to mark his 30th anniversary as an MP.

Corbyn stood on picket lines because it was the right thing to do; he was proved right by history, time and again: on Ireland, South Africa and Iraq; he campaigned in other MPs’ constituencies even if they were unwinnable — for example in Thanet, which he visited not once, but four times in 2015. All this, and his insistence on not making personal attacks on opponents, built up a reserve of goodwill which helped him secure the necessary number of nominations for the leadership in 2015. It explains why in August of 2016, when most politicians (and activists) were on holiday, 4,000 people attended a meeting in a London suburb at five days’ notice. Corbyn is not an electrifying speaker like Barack Obama. But unlike many politicians, he means what he says and he likes meeting people. His 34-year record as an MP shows he has the conviction, tenacity and unruffled single-mindedness to deliver his agenda.

By 2016, a few commentators — despairing at Labour’s then-poor poll ratings — began to look for alternative leftwing candidates to Corbyn. But none of those touted from the 2015 intake (virtually no new left candidates were allowed through under the Blair-Brown regime) had the fibre to stand up to the pressures of Labour’s rightwing MPs, its internal apparatus, the media and countless other hostile pressures. A well-intentioned Ed Miliband, elected leader in 2010 alongside a respectable surge in membership numbers, quickly succumbed to such pressures and most similarly inexperienced figures would do the same.

The Next Steps

Yet for all the excitement Labour’s 2017 general election campaign generated, Corbyn did not win. Britain remains in the hands of an internally divided, unstable Conservative minority government, which historical precedent suggests is unlikely to last its full term. Labour has to look like a government in waiting, but if it is to do so, and if it is to win the next election and then transform Britain, it faces a number of challenges.

Firstly, the Party needs root-and-branch reform. The structures need to be democratised so the influx of new members can play an effective role in shaping policy and selecting candidates at all levels. The Party needs to become a social movement in its own right, a campaigning organisation as well as an electoral machine. The Party apparatus will need to be overhauled to become more responsive to these new realities. And the parliamentary party, the source of so much disloyalty, hostile briefing and leaks against Corbyn over his first two years as leader, needs to be held accountable, so that MPs understand that their sabotaging of the possibility of a Labour government will not be countenanced by local members and supporters.

Secondly, a modest lead in the opinion polls is no guarantee of future success. The next general election, whenever it comes, is unlikely to be fought under the same conditions as 2017. Then the Conservatives were complacent and blindsided by the rise of Corbyn: next time they will not be, and the international and domestic contexts may be very different.

Secondly, a modest lead in the opinion polls is no guarantee of future success. The next general election, whenever it comes, is unlikely to be fought under the same conditions as 2017. Then the Conservatives were complacent and blindsided by the rise of Corbyn: next time they will not be, and the international and domestic contexts may be very different.

Thirdly, Labour’s policies cannot stand still. On a range of issues – from Brexit to taxation, from immigration to constitutional change – voters will expect considerable modification of the ideas that were put together in 2017 in the context of a snap election. It is to the development of that programme that this book seeks to make a contribution.

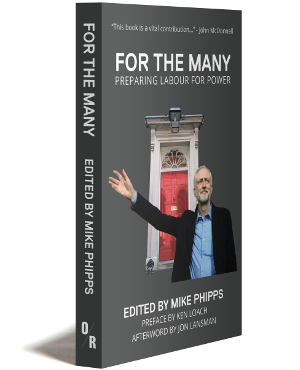

This is an adapted extract from ‘For the Many: Preparing Labour For Power’, edited by Mike Phipps, with a preface by Ken Loach and an afterword by Jon Lansman.

Ceasefire readers can receive a 20% discount by ordering from the OR Books website using the code: THEMANY.

Leave a Reply