Nincompoopolis: The Follies of Boris Johnson Books

Arts & Culture, Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, August 7, 2018 0:00 - 0 Comments

By Alex Baker

While most of us can experience failure as a setback, while the inevitable and sad gravity of failure pulls us down at least in the short term, upper class men in this country always seem to land on their feet. Rightfully they should be a mystery phenomenon, the product of some ancient hex, or at least a natural wonder that brown signs on country roads indicate for the perusal of bored families on rainy weekends. And in this world, surely it would be Boris Johnson who would have the record for the most caravans backed up down the A303, the highway to ‘staycation’ sun. That is, if he wasn’t already his own very profitable cottage industry.

While most of us can experience failure as a setback, while the inevitable and sad gravity of failure pulls us down at least in the short term, upper class men in this country always seem to land on their feet. Rightfully they should be a mystery phenomenon, the product of some ancient hex, or at least a natural wonder that brown signs on country roads indicate for the perusal of bored families on rainy weekends. And in this world, surely it would be Boris Johnson who would have the record for the most caravans backed up down the A303, the highway to ‘staycation’ sun. That is, if he wasn’t already his own very profitable cottage industry.

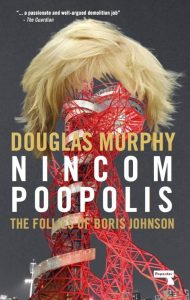

Doug Murphy’s Nincompoopopolis is a suitably and rewardingly vicious cash in on Borisiana, and a neat précis of the architectural legacies of Johnson in his time in power in London. Here we find a description of a mayor whose desire for a legacy was foxed by his own inability to maintain the attention needed to give the projects he started the finish they needed, leaving a trail of architectural mishaps, a mayor who promised to preserve heritage but built a shark-toothed mess of semi-empty glass towers bisecting the city from Southwark to Liverpool Street. Murphy describes a man defined not so much by his contradictions as the disturbing probability that a dark logic of ritual magic underlay all this, some belief in the rejuvenating powers of gherkins, phones, pyramids and cable cars.

Boris wasn’t mayor of some regional city, one of those odd eccentrics you get in charge every few decades in smaller towns, where the local fetishes of voters propel a maverick to power on the back of a dog poo campaign. Oh no, were it only so easy. Johnson was elected by London, which, we are constantly inveighed-upon to believe, is a city unlike any other. How do seemingly sensible, moderate, highly-educated people, in the most powerful, diverse, and affluent city on earth, vote for catastrophe?

The first thing to note is that, as a town planner, Johnson wasn’t that unusual (nor, as Murphy observes, is the office of Mayor of London all that powerful). Boris mostly built on the established broad framework for urban development in wealthy nations during the first half of the millennium. Urban governance is rife with what the geographer Jamie Peck termed the contagion of ’Fast-Policy’ where ideas are copy+pasted from think tank reports into policy documents or pilfered from other cities, and it often treats planning as a kind of magic.

It’s long been a world of invisible “creative classes” that can regenerate the economy, or one where high-rise buildings drive their inhabitants to crime through the power of architecture. This is a political culture that had already created its own tangled justifying regimes of truth, and eagerly absorbed and fuelled these strange formulations; and it was one where, in 2008, Boris could slip right in, promising the classic political quick fix of law-and-order, mobilising suburban Londoners who felt threatened by the inner city.

Beneath this mysticism was what Murphy terms a ‘Faustian pact’ with development and finance, continued from the his predecessor’s era. Despite ditching some of Livingstone’s more symbolic policies and projects, such as an oil deal with Venezuela, and the much-maligned bendy bus, Boris retained the core feature of London’s economy from the 1980s onward: the use of land and housing as a speculative opportunity in which to invest money.

As Anna Minton explains concisely in her recent book Big Capital, the hyper-commodification of urban land (and increasingly urban volume) have combined to produce a geography of hostility and fragmentation in the name of financial expediency. This property glut was sustained by councils, Labour and Tory, unconcerned by, and even actively relishing, the social cleansing of housing tenants from large estates to the outer suburbs, and some as far away as York and Hull. Watching over them all was, and is, the square mile of the City of London, its own strange enclave, with its own laws, its own police, and its peculiar institutions, wielding The Evening Standard and the threat of Capital Flight.

By now the inequalities of wealth that have emerged in London as a result of this are well documented, from the new ghettos to the ‘Alpha Territories’. Tower Hamlets, South Kensington, Hyde Park and the Isle of Dogs all boast both types. Indeed, Johnson’s most symbolic architectural legacy is one Murphy only briefly touches on, but is hidden from public view — urban basements constructed by the super-rich; “over 1,000 gyms, 376 pools, 456 cinemas, 381 wine stores and cellars and 115 staff rooms”. The recurrent urban myth of Johnson’s Mayorship, that countless JCBs lay abandoned in backfill under the soils of Chelsea and Belgravia, abandoned like so many mechanical Brachiosauri, was too resonant to resist.

The reality is that the glut is likely over, and the latest information indicates a market starting to cool — high-end developers are offering giveaways to entice buyers. Bloomberg and the Financial Times have both noted a decline in overseas investment, and house prices are falling. It’s easy to conceive of a property market in terms of shifting units, sold at auction or out of a dealership one at a time, yet in practice, as in many cities, much of the most expensive new property in London is still in the process of being sold ‘off plan’; marketed — through payments due in stages, from initiation on the drawing board through to its completion — out of hotel suites in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Shanghai. It will be years before the extent of any downturn in buyers is recognised, much too late to halt long-term planning decisions that hammer local residents in favour of transnational investment.

The image of a barren wasteland of capital is only part of the story. The London that Johnson inherited and oversaw was, after all, a place of intense intellectual production. It was a city of almost 40 Higher Education institutions, and the ever-dominant theatres, museums and galleries. But it was also a city of criminalised innovation: an unknown number of pirate radio stations, squatters, artists studios, music venues, small time drug dealers, and phone kiosks, constantly working out how to bend or evade the rules that Labour and Ken Livingstone had been escalating, and were gradually starting to feel the shutdown. A now-famous study, run from 2011 to 2013 by researchers at the LSE, found that, among other things, the average number of languages spoken by traders in Peckham Rye Lane was between four and six (embarrassingly enough, more than the average LSE academic). Cities are built by such complex and incremental forces, shaped by what social scientists loftily call the ‘encroachment of the everyday’.

It is not a stretch to say this inequality was — and is — maintained through violence. The daily experience of thwarted potential came forward most prominently in the public disorder that marked Johnson’s mayorship, climaxing with mass rioting in response to the state murder of Mark Duggan, where police were repeatedly humiliated and outwitted by smartphone and blackberry users. This was followed by a round of vicious reprisals in the courts, including the tragic case of James Best, who died in Wandsworth prison after being jailed for stealing little more than a gingerbread man, a child’s treat.

The riots were the pretext (if one was needed) for a wave of law-and-order activities. Easily the most malicious of Johnson’s white elephants was the purchase of a £200,000 set of water cannon trucks, a riot control technology, eventually rejected by then Home Secretary Theresa May due to the debilitating effects of their blunt force on the human body and their capacity to cause hypothermia in cold weather. Johnson cloaked this authoritarian streak in policy with a kind of communitarian amiability in publicity, appearing armed with a broom to help with the post-riot cleanup, seizing on a spontaneous response to the riots that Murphy argues was imbued with a racialised and deeply revanchist narrative to recover the city for the upstanding citizen.

This strong sense of leadership saw Johnson get London to put on a united front for the 2012 Olympics, albeit with mass arrests outside the park during the opening ceremonies after months of protest. Nevertheless the civic nationalism of the opening ceremony melted the iciest of skeptical hearts. This was a deft blending of reactionary Toryism and social populism that suckered in liberals. Choreographed routines in praise of the NHS had even hardline naysayers cooing at the same time as Cameron proposed to Market the NHS overseas as a brand. The Olympics created a delusion of a tolerant, unique nation, one that persisted until the 20-year project of Euroscepticism Johnson had also been building shattered it. A full ideological accounting of the toxic lineage of the Olympic opening ceremony through to Brexit has yet to be made, but in any case, once the Union Jack went up, it never really came down.

As a recent report on the Olympic legacy by the London Assembly found, very few of the aims set out have been met. Wages in the communities near the main Olympic Park have declined, while many indices of deprivation have increased. The gap in physical and sporting activity between income brackets, surely the most basic test of the construction of any new public sports complex for encouraging mass participation, has widened, with the poorest even less active. But the narrowness of vision at work in the Olympics should have been self-evident; how on earth could a month of sport ever resolve three decades of growing inequality and neglect? How was it so hard to conceive of a social programme of development without it being embedded in the national ego, urban ‘regeneration’ and sports-industrial complexes?

This indignity of the social is reflected in indignity of the aesthetic. Murphy describes how the Olympics showcased Johnson’s role as a Medici to the mediocre. With star architects and firms like Arup and Zaha Hadid, he commissioned work that confused iconography with incongruity, with the crowning achievement of the ArcelorMittal Orbit at the Olympic Park, a tangle of intestinal-looking tubes that offers a lacklustre view of the surroundings and costs £5 to climb.

The Garden Bridge, on the need for an ineffectual public space that was neither a Garden, nor a Bridge, was the icing on the cake. Murphy points us to Boris’ ongoing close relationship to the Bridge’s designer, Thomas Heatherwick, whose works, from the collapsing B of the Bang in Manchester to the fading Blue Carpet for Newcastle, to the overheating ‘roastmaster’ buses, has a tendency to unintentionally embrace the principles of auto-destructive art. It is very inviting to speculate what these two men see in each other, though perhaps a proximity to calamity might be one.

The problem is that failures, accidents, gaffes, and collapses have deadly consequences. If Minton’s book addresses the economic question, and Murphy’s the problem of design, then there is a third book urgently necessary about the ecology and material infrastructure of London. A year on from the fire at Grenfell Tower, the safety of countless refurbished buildings is being called into question.

The most overlooked significant event during Boris’ time over London was the closure of the Thames barrier 50 times in the 2013-14 season thanks to heavy rainfall. Then there is the filthy air, electrical and telecommunications demand, the literally sclerotic sewer system, London’s sinking foundations in the clay soil of the Thames Valley, and the city centre’s vulnerability to rising rainfall and sea levels are combining with a concept of urban governance driven by austerity and privateering. London is the sterling billionaire and tuberculosis capital of Europe.

So despite talk of exceptionality, Murphy’s book shows us that London is not immune to the punitive urges and the urban revanchism found elsewhere, that it, too, can produce Rudolf Giulianis or Rob Fords. These people are not an error of a system. They are that system’s logical output, an overeager embrace of business as usual in urban policy. Let’s be clear about this, Boris was what middle class London wanted and what middle class London got.

So despite talk of exceptionality, Murphy’s book shows us that London is not immune to the punitive urges and the urban revanchism found elsewhere, that it, too, can produce Rudolf Giulianis or Rob Fords. These people are not an error of a system. They are that system’s logical output, an overeager embrace of business as usual in urban policy. Let’s be clear about this, Boris was what middle class London wanted and what middle class London got.

Nincompoopolis: The Follies of Boris Johnson

Douglas Murphy

Paperback (with free e-book) £9.99

Publication: September, 2017

Published by Repeater Books

Leave a Reply