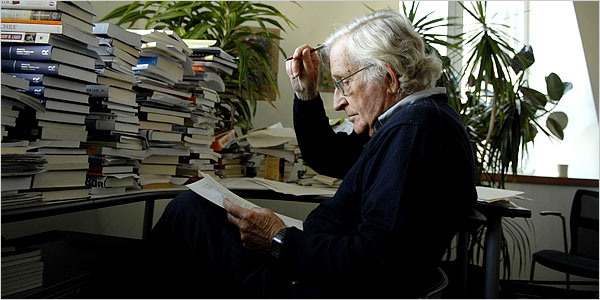

Interview Noam Chomsky (2010)

Ideas, Interviews - Posted on Thursday, September 23, 2010 9:41 - 12 Comments

INTRODUCTION

by Hicham Yezza

Little of novelty or substance can be added to the millions of words that have already been written or spoken about Noam Chomsky. But it’s worth repeating a couple of them, if only to underscore the sheer, breathtaking scale of his achievements.

First, he is the eighth most-cited author in the world, ever. Sharing the top ten with him are: Marx, Lenin, Shakespeare, Aristotle, the Bible, Plato, Freud, Hegel and Cicero. Put simply, to ignore his work is to court unimpeachable irrelevance.

Second, he is, without a doubt, our Bertrand Russell: a man of extraordinary intellectual achievement, the father of modern linguistics, a pioneer of cognitive science, a political thinker of astonishing breadth and erudition, a writer of great moral courage in the face of cruelty and oppression, a tireless campaigner for peace and justice, and a robust voice of reason in the wilderness of despair and cynicism that is our modern world.

Noam Chomsky, the world’s greatest intellectual, agreed to take time out of his dauntingly congested schedule to grant Ceasefire this interview. He is currently in Mexico giving a series of talks, almost bringing to a close a marathon journey around the world that has taken him, in the past few weeks, from Palestine to China, addressing, in the process, audiences of thousands of people hungry for his lucid, trenchant insights and wisdom.

In more than six decades, from his earliest piece of political writing, in 1939, about the tragic fall of Barcelona in the Spanish civil war, to this interview, conducted yesterday, Chomsky’s commitment to social justice has been unwavering. His belief in the power of reason against the reason of power is an inspiration to us all.

NOAM CHOMSKY: AN INTERVIEW

Conducted on 22/09/2010 In your recent London lectures, you recounted a wonderful anecdote about student radicalism days in MIT and also at the LSE. Do you think the intellectual/academic culture has changed drastically since then? You compared the Iraq war protest movement favourably to the anti-Vietnam one due, largely, to the fact mass opposition to the Iraq war actually started before the invasion. Do you still see the anti-Iraq-war movement in that positive light, especially considering how small it is now, seven years on?

In your recent London lectures, you recounted a wonderful anecdote about student radicalism days in MIT and also at the LSE. Do you think the intellectual/academic culture has changed drastically since then? You compared the Iraq war protest movement favourably to the anti-Vietnam one due, largely, to the fact mass opposition to the Iraq war actually started before the invasion. Do you still see the anti-Iraq-war movement in that positive light, especially considering how small it is now, seven years on?

The anti-Iraq-war movement was always much too small in my view, though in fact much larger than the anti-Vietnam-war movement at any comparable stage – a crucial qualification often ignored. I think there is good reason to believe that the anti-Iraq-war movement contributed to the US defeat in Iraq as contrasted with its considerable victory in Vietnam, already evident 40 years ago – abandonment of core war aims in Iraq, while they were basically achieved in Vietnam.

The global recession and crisis in the past two years have yielded a lot of popular anger against financial institutions and governmental subservience to them. And yet, nothing structural has shifted in terms of people saying: we want a different system. Do you think the left has made mistakes in responding to the crisis?

A lot more can be done, and should be. To take merely one example, the left could be active in efforts by workers and communities to take over production that is being shut down by the state-capitalist managers and convert the facilities to urgent needs, such as high-speed public transportation and green technology. Just one case.

Your 1970 lecture on ‘Government in the Future’ is now a classic of the genre. Does it still reflect your views entirely or has there been a change? Many find it now extremely rare to see this sort of explicit, serious engagement with fundamental ideas about how society should be run, as if the case for state capitalism has been definitively made and the left should just give up trying to argue for radical alternatives. Is this your view? Or do you think the situation is more hopeful?

I have not changed my views on these matters – of course expressed only sketchily in this talk. In fact, I had pretty much the same views as a teen-ager. The left should very definitely be actively engaged in critical analysis of the destructive system of state capitalism and in developing the seeds of the future within it, to borrow Bakunin’s image. I think there are many opportunities, and some of them are being pursued, though still on much too limited a scale.

Turning to the Middle East, regarding the movement which calls for boycotting, divesting from and sanctioning (BDS) Israel, why do you think there is such a drastic disagreement between yourself and people (such as Naomi Klein) who traditionally agree with you wholeheartedly on Middle-East and other issues? Is this a mere issue of tactics? Is the BDS movement doing more harm than good?

There is an interesting mythology that I have opposed the BDS movement. In reality, as explained over and over, I not only support it but was actively involved long before the “movement” took shape. BDS is, of course, a tactic. That should be understood. Norman Finkelstein warned recently that it sometimes appears to be taking on cult-like features. That should be carefully avoided. Like all tactics, particular implementations have to be judged on their own merits. Here there is room for legitimate disagreement. I have been opposed to certain implementations, particularly those that are very likely to harm the victims, as unfortunately has happened.

More generally, I think we should question the formulation you gave. It is convenient, particularly for Westerners, to regard it as an “anti-Israel movement.” There are obvious temptations to blaming someone else, but the fact of the matter is that Israel can commit crimes to the extent that they are given decisive support by the US, and less directly, its allies. BDS actions are both principled and most effective when they are directed at our crucial contribution to these crimes, without which they would end; for example, boycott of western firms contributing to the occupation, working to end military aid to Israel, etc.

My understanding is that you believe a one state solution can only happen via a two state solution. Is this correct? If so, do you think a call for a one state solution is detrimental to Palestinian interests? Or merely unhelpful?

I have never felt that we must honour the boundaries imposed by imperial violence, hence do not see a solution keeping to the Mandatory boundaries as something holy, or even desirable in the long-term. A “no-state solution” eroding those boundaries is, in my view, both preferable and conceivable, a matter I have discussed elsewhere. However, I know of no suggestion as to how to reach that goal without proceeding in stages, at first by way of a “one-state” (bi-national) solution of the kind I have advocated since the 1940s, and still do.

There have been periods when it was feasible to move fairly directly towards a settlement of this sort – pre-1948 and from 1967 to the mid-70’s, and during those periods I was quite actively involved in urging direct moves towards such a settlement. Since Palestinian nationalism became an active force in the international system in the mid-1970s, I know of no suggestion as to how to reach this limited goal without proceeding in stages, at first by way of the two-state solution of the overwhelming international consensus, blocked for 35 years by the US (and Israel) with rare and temporary exceptions.

Calling for a one-state (or better, a no-state) settlement is fine, as are many other calls, for example, for eliminating nuclear weapons, warding off environmental catastrophe, etc. But we should distinguish between “calls” and true advocacy, which requires sketching a path from here to there. The latter is the more serious and demanding task, both in thought and action.

You have said before that you would accept whatever solution the Palestinians/Israelis wanted (one state/two state/etc), but you also said that if, for instance, Somalis were in favour of an international course of action that, in your view, would actually harm them, you naturally wouldn’t participate in it. How would you clarify the distinction between the two moral imperatives? Is it possible at the same time to listen to the Palestinians’ wishes but also independently decide what’s good for them?

If I said that, it was misleading. I have no authority, right or ability to “accept” or “reject” international agreements. Speaking personally, I do not regard nation-states as acceptable institutions, except as temporary expedients. It is always possible, and often imperative, to decide that the wishes of some population are not good for them. We all do it all the time, surely. And if we are serious about decent human values, we may often decide not to participate in actions that populations choose to carry out. I see no general issues here, though particular cases always raise questions.

You’ve recently dismissed the idea that China and India can pose any serious challenge to Western dominance. What will the post-unipolar world look like in your view, if current trends continue?

They do pose a serious challenge, something I have been speaking and writing about, though much of the excited rhetoric about the topic is highly misleading. For many years the world has been becoming more diverse, with more diffusion of power. In the past decade, even Latin America – which the US has traditionally taken for granted – is drifting out of control.

One striking illustration today is Iran’s nuclear programs. For the US and most of Europe, that is THE problem of the day. This is “the year of Iran” in foreign policy circles, and the “Iranian threat” is depicted as the greatest current danger facing the world. The US is demanding that China and others meet their “international responsibilities”: to adhere to unilateral US sanctions, which have no force other than what is conferred by power. Few are paying attention. Not China, not Brazil, not the nonaligned countries (most of the world), not even Iran’s neighbors, particularly Turkey.

Recent reports have shown inequality in the US to be greater than ever. And yet all we hear of is the rise of the tea party movement and its crusade against Obama’s “socialist” agenda. Is this because people are campaigning against their own interests out of ignorance? Or is it that those who really suffer from inequality (the very poor) are completely cut off from the political debate in the first place and thus utterly voiceless?

The tea party movement itself is quite small, though heavily funded and granted enormous media attention, Much more significant is the great number of Americans, probably a majority, for whom it has some appeal, even though its programs would be extremely harmful to their interests if implemented. There is tremendous anger in the country, and bitter opposition to virtually all institutions: government, corporations, banks, professions, the political parties (Republicans are even more unpopular than Democrats), etc.

At the same time, careful studies show that people largely retain attitudes that are basically social democratic, facts rarely discussed in the media. The anger and frustration are understandable: for about 30 years, real incomes have stagnated for the majority, working hours have increased (far beyond Europe), benefits – which were never great – have declined, while public funds are bailing out the rich and economic growth is finding its way into very few pockets.

In manufacturing industry unemployment is at the level of the great depression, and these jobs are not coming back if the bipartisan policies of financialization of the economy and export of production proceed. But anger and frustration can be very dangerous, unless focused on the real causes of the plight of the population. That is barely happening, and the outcome could be ominous, as history more than amply illustrates.

You often state that global warming and nuclear war are the two great dangers threatening human life. Why do you think there’s such resistance against believing in human-caused climate change? It’s difficult to put this simply down to financial interests since many “sceptics”, as they call themselves, seem genuinely convinced global warming is some sort of hoax. Are they just blinded by propaganda?

There is a very small group of serious scientists who are skeptical about global warming. Major sectors of business have been entirely open about the fact that they are running propaganda campaigns to convince the public that it is a hoax. That is an interesting phenomenon, because those very same corporate executives probably share our views on the severity of the crisis. But they are acting in their institutional capacity as corporate managers, which require them to focus on short term gain and to ignore “externalities,” in this case the fate of the species.

The problem is institutional, not individual. As for the public, many are genuinely confused. That is not surprising when the media present a “debate” between two sides – virtually all scientists versus a scattering of skeptics – while incidentally ignoring almost entirely a much more serious array of skeptics within the scientific world, namely those who believe that the general scientific consensus is much too optimistic. There are doubtless other reasons too. Taking the problem as seriously as we should leads to difficult choices and actions. It is easier to transfer the problems somewhere else, in this case to the world’s poor and to our grandchildren.

We had a discussion recently with some of our readers about independent media outlets receiving money from foundations. Some argue this is fundamentally wrong because even if it comes with no explicit strings attached, it would still affect the way an organisation reports and analyses the news. A case that was mentioned was Democracy Now!, which we love. Do you think receiving donations from charities/foundations is fine, or is it merely a lesser evil to be avoided if possible?

I do not feel that it must be avoided in principle, though naturally considerable caution is necessary.

Our next print issue, out in October, will feature a celebration of the late Edward Said. Why should young students/activists pay a great deal of attention to his legacy?

In his highly original and justly influential scholarly work, and in his dedicated and courageous activism in support of suffering and oppressed people, Edward Said – a close and highly valued friend – was one of those very rare figures who actually fulfilled the responsibility of intellectuals that he wrote about so compellingly. He is an inspiring model.

Thank you so much Noam.

Hicham Yezza is the Editor of Ceasefire.

For Noam Chomsky resources, please visit www.chomsky.info

An extended version of this interview will be published in our forthcoming Autumn print issue, out in October. For pre-orders please email: [email protected]

To join the Ceasefire mailing list, add your email address (top right corner of this site) and click on ‘subscribe’, you will then receive a monthly update of new articles. No spam, ever.

To join the Ceasefire mailing list, add your email address (top right corner of this site) and click on ‘subscribe’, you will then receive a monthly update of new articles. No spam, ever.

Previous and future print issues of Ceasefire include interviews featuring Noam Chomsky, Norman Finkelstein, Michael Albert, and Gavin Hayes as well as articles on Bob Dylan, Radiohead, Philip Roth, J.S. Mill, Zizek, Animal Collective, Deleuze and Guttari, Obama, Marx, Mahmoud Darwish, Edward Said, Samuel Beckett, Morrissey, Tony Judt, and much, much more. They can be ordered here. A subscription option will become available in the near future.

12 Comments

JB

the pair

Wow…a great interview in general but you also asked, in almost the exact words I would have used, two clarifying questions I’ve always wanted to ask Prof. Chomsky.

He’s right that there’s a “mythology” about his supposed opposition to BDS which is odd when you’re familiar with his work; ditto for the One State “solution”. He’s never seemed in disagreement with either idea but simply pragmatic (in the rational sense as opposed to Obama’s “what will please my corporate backers” sense) and aware after his many years of activism that ideas only go so far and need action to back them up. It was refreshing to see his views explicitly clarified.

Great work.

Great interview.

Ceasefire Magazine – Interview: Noam Chomsky « Chomsky Watch

[…] via Ceasefire Magazine – Interview: Noam Chomsky. […]

Steve Garrett

I assume that Chomsky sees no threat with an evil faith based regime who thinks ther is a better world after this obtaining a nuclear weapon?

Tom

Actually he’s been a fairly consistent critic of Israel over the years.

Ceasefire Magazine – This week in Ceasefire

[…] Interview: Noam Chomsky […]

Johnny Blaze

“the US defeat in Iraq as contrasted with its considerable victory in Vietnam, already evident 40 years ago – abandonment of core war aims in Iraq, while they were basically achieved in Vietnam.” How? US war aims in Vietnam were to prevent re-unification and establish control of rubber oil and tin in South East Asia; in both these efforts they were defeated by the Viet Cong. Whereas in Iraq their war aim was to put in place a client regime that would allow easy access to Iraq’s oil deposits and in this it has succeeded. Chomsky should just have accepted that while the anti Iraq war movement may have been the first anti-war movement to start before a war has taken place it has gone downhill ever since in contrast to the anti Vietnam War movement which went from strength to strength at a similar juncture (7 years after the start of the war)

I also disagree with the use of the phrase “state-capitalist” to describe western economies. State Capitalism is when the state owns the means of production as in countries with Leninist governments and also many Gulf countries that have never had any reason to privatize. In western economies its precisely the opposite; “State Capitalism turned on its head” (as Mussolini described his vision of a fascist economy.) The state is under the control of large corporations, such a system is better defined as Corporatism.

Other than that though it was a great interview. Chomsky is always worth listening to

Nice interview and always a pleasure to hear Chomsky ruminate. Whether the US did in fact achieve its goals in Vietnam… sounds like Chomsky is taking lessons from Zizek on exageration. One thing I find a real pity here is that Hitch didn’t address the causes of 911 with Chomsky, because some years ago when approached on this issue, Chomsky had responded that there was nothing serious to talk about until there had been some peer reviewed research from the appropriate technical fields (engineering, etc.). However, now there has been – so like a lot of other keen listeners, we want to know what Chomsky’s thoughts are in light of the reasonably clear evidence of the use of demolitions in the 911 attack (presumably as part of a larger false flag operation, etc.).

Anyhow, otherwise, nicely done.

MIT Professor Noam Chomsky’s Ties to the Military (continued)

by BOB FELDMAN

S. military.

“…He was…interviewed by laboratory director Jerome Wiesner for the position…Chomsky was hired as a full-time faculty member, which meant that he was required to spend half his time working in the research lab…Here, his ASPECTS OF THE THEORY OF SYNTAX was hatched…The funding for the research published in ASPECTS was provided by `the Joint Services Electronics Program (U.S. Army, Navy and Air Force), the Electronics Systems Division of the U.S. Air Force, the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and NASA…” (from NOAM CHOMSKY: A Life of Dissent by Robert Barsky).

Jerome Weisner later became the head of JFK’s Science Advisory Committee during the early 1960s; and according to the 1965 annual report of the Ford Foundation-subsidized Institute for Defense Analyses Pentagon weapons-research think-tank, Jerome Weisner was an Adviser to IDA’s Jason Division group of university professors who performed counter-insurgency, Vietnam War-related weapons research every summer during the 1960s Viet Nam War Era.

When students shut down Columbia University in 1968 in support of the demand that Columbia resign its institutional membership in IDA, MIT Professor Chomsky constructed a left anti-war rationalization for opposing the Columbia student revolt – but he did not disclose at the time that an IDA Jason Division consultant, Jerome Weisner, was the person who hired him as an MIT professor and military lab researcher during the McCarthy Era.

As Barsky also notes in his NOAM CHOMSKY: A Life of Dissent book: “While he admired `the challenge to the universities’ that the students were so vehemently presenting, Chomsky thought their rebellions were `largely misguided,’ and he `criticized [them] as they were in progress at Berkeley (1966) and Columbia (1968) particularly.”

Today, of course, MIT is still the 12th-largest recipient of U.S. Air Force war research contracts and among the top recipients of U.S. Air Force war research contracts.

Also, there doesn’t appear to be any reference to the $350,000 Inamori Foundation/Kyoto Prize grant that was given to MIT Professor Chomsky in the late 1980s, in the index of the Barsky biography of him.

The reference to the military links is also in CAMPUS, INC.: Corporate Power in the Ivory Tower, edited by Geoffry D. White,. In an interview in the last chapter, MIT Professor Chomsky says: “…The universities did receive large-scale subsidies, quite often under the cover of defense.

“I happened to be on a committee that was set up to investigate these matters about thirty years ago. It was the first such committee for me as a result of student activism that was concerned about the reliance of MIT on military spending, what it meant, and so on. So there was a faculty/student committee set up and I was asked to be on it, and I think it was the firstreview ever of MIT fundidng…My memory is that at that time, about half of MIT’s income came from two military laboratories. These were secret laboratories. One was Lincoln Labs and one then called the I Labs, now the Draper Labs, which at the time was working on guidance systems for intercontinental missiles and that sort of thing. These were secret labs and that was approximately half of the income. And, of course, that income in all kinds of ways filtered into the university through library funds and health funds and so on. Nobody knew the bookkeeping details and nobody cared much, but it was an indirect subsidy to the university.

“The other half, the academic budget, I think it was about 90 percent Pentagon funded at that time. And I personally was right in the middle of it. I was in a military lab. If you take a look at my early publications,they all say something about Air Force, Navy, and so on, because I was in a military lab, the Research Lab for Electronics. But in fact, even if you were in the music department, you were, in effect, being funded by the Pentagon because there wouldn’t have been a music department unless therewas funding for, say, electrical engineering. If there was, then you coulddribble some off to the music department. So, in fact, everybody wasPentagon funded no matter whatever the bookkeeping notices said.

“Well, it’s important to recognize that during that period, the university was extremely free. The lab where I was working, the research lab for electronics, was also one of the centers of anti-Vietnam War resistance. We were organizing national tax resistance and the support groups for draft resistance were based there to a large extent. I mean, I, myself, was in a jail repeatedly at the time. It didn’t make any difference. The Pentagon didn’t care. In fact, they didn’t care at all as far as I knew.

“Their function, they understood very well, is to provide the cover for the development of the science and technology in the future so that the corporate system can profit.

GW: So they were just too big and powerful to be threatened. You were too minor of a threat?

MIT Professor Chomsky: “They just didn’t care. What happened at the administrative level I didn’t know, but nothing ever got to us. I hadperfectly good relations with the administration. In fact, I’d tell them if I knew I was going to get arrested. I had no particular interest in embarrassing them, but it didn’t matter.

GW: Okay, but before things started shifting more and more to corporate funding, are you saying that when the funding came from the Pentagon it was completely `free’?

MIT Professor Chomsky: “Overwhelmingly it was free. You could do pretty much waht you wanted. And there was nothing secret on campus. In fact, we investigated secrecy specifically in the committee. Although it was regarded in the government as military-related work, there was virtually nothing that was secret. In fact, the parts that were secret were mostly an impediment to research. It wasn’t because anybody wanted it (secrecy), it was just some technical detail that hadn’t been ironed out. You could do what you wanted in your personal and politicallife, and also in your academicand professional life, wihtin a broad range. It [MIT] must’ve been one of the most free universities in the world.

GW: Who had access to the results of all this work and research?

MIT Professor Chomsky: “But that’s a joke. I remember a discussion once with the head of the instrumentation lab, which was the lab that was working on guidance stystems for intercontinental missiles. Of course it was all classified, but he said that from his point of view, he woul be perfectly happy to declassify everything and give the books to the Russians and the Chinese. He said they can’t do anything with them anyway. They don’t have the industrial capacity to use the technology that we’re developing. So thewhole effect of the classification system was to impede communication amongthe American scientists.

GW: With what result?

MIT Professor Chomsky: “Well, nothing, I mean, they kept that system classified and sort of spun it off, it’s now a secret lab, independent ofMIT. But, in answer to your question, right now, for example, there’s anagency in the Pentagon, DARPA, the Defense Advance Research Project Agency,which has been the center of innovation for many years. It’s where theInternet comes from. ..”

Of course, what MIT’s Chomsky is failing to disclose in this interview is that if you check out MIT’s web site and the Draper Lab web site, the military research that’s going on today at MIT LIncoln Laboratory and Draper Lab is related to space warfare technology development.

And DARPA is more about developing the weapons technology that’s been used during the last few years than just doing “Internet” research.

The MIT LIncoln Laboratory web site states, for instance: “MIT Lincoln Laboratory’s Suface Surveillance Program develops advanced technology for detecting and identifying vehicles and facilities on and beneath the surfacein wide-area, heavily cluttered and electronically hostile battlefields. MIT Lincoln Laboratory has developed clutter cancellation technology that isused in today’s airborne surveillance systems…We are developing technologycapable of detecting and tracking moving targets that are partially or fullyobscured by foliage.”

And Draper Lab President Vincent Vitto said in 2001: “Draper’s core work remains focused on the development of innovative solutions for theDepartment of Defense’s future technology needs…. These areas includeprecision targeting and weapons systems…”

MIT Professor Chomsky’s ties to the military during the McCarthy era of the 1950s

By Bob Feldman

Draper is working on systems for land battle that focus on the dismounted soldier, Global Positioning System (GPS), precision munitions, and missiles. Under the leadership of the U.S. Army’s Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center(Natick), development activities include aircraft mission planning and parafoil GN&C software for the Army/Air Force Joint Precision Air Drop System (JPADS) operations on C-130 and C-17 aircraft. The airdrop mission planner includes models for several unguided airdrop systems (ones that cannot be controlled during descent). These models are the basis for developing optimal air release points. Government-conducted testing has demonstrated that JPADS has improved landing accuracy for payloads over existing methods by 56% and 70% for unguided airdrop systems deployed from C-130 and C-17 aircraft, respectively.

JPADS’s guided parachute supply delivery system, designed to reduce the risk to troops during resupply missions, made its combat debut in Afghanistan on August 31, 2006. Draper was responsible for the now-fielded mission planning system software and also demonstrated the flight of an advanced guidance software package for use on a precision airdrop system being considered for early field use.

Draper is developing low-cost guidance electronics and GN&C software for the Navy’s Ballistic Trajectory Extended Range Munition (BTERM) program. The Laboratory demonstrated precision guidance of long-range, gun-fired projectiles in support of ground maneuver warfare. The Draper-developed Low-Cost Guidance Electronics Unit (LCGEU) demonstrated new maximum range and precision impact levels for two types of Navy projectiles: the EX-171 Extended Range Guided Munition (ERGM) and BTERM. These tests proved the LCGEU’s utility as the first “common” guidance electronics for multiple Navy projectiles.

http://www.draper.com/air_warfare_ISR/air_warfare.html

Intelligence Solutions

Draper’s Air Warfare and ISR directorate is dedicated to improving DoD intelligence and US Air Force combat functionality through the innovative design, development, and deployment of information decision systems and intelligence data handling capabilities.

Geospatial Intelligence systems, tools, processing, and data management

Targeting and target planning applications, tools, systems, and networking

Sensor, video, and imagery processing, analysis, exploitation, visualization

ISR Systems and Capabilities

Draper provides systems analysis, design, and rapid prototyping for airborne ISR processing, systems, and components. Draper’s expertise in sensor systems, inertial technology, planning optimization, and information decision systems comes together to provide unparalleled capabilities for development, test, and evaluation of manned and unmanned ISR systems.

Mission Integration & Optimization for manned or remotely piloted systems

Advanced software, algorithms and processing for sensor/system cross-cueing

System analysis, design, and processing for multi-sensor, multi-platform ops

Precision Engagement – Precision Strike

We apply our multi-discipline engineering and development expertise to technologies that enable accurate location and timely prosecution of targets in dynamic USAF combat and close air support environments. This same multi-discipline approach enables innovative solutions for test-range evaluation of weapons and optimization of range instrumentation.

Multi-sensor/phenomenology processing for detection of targets and change

Automated target acquisition and processing, tracking, and data networking

Rapid geo-location & geo-registration for dynamic targeting solutions

Susan Hockfield;

Susan Hockfield (born March 24, 1951)[1] is the sixteenth and current president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Hockfield’s appointment was publicly announced on August 26, 2004, and she formally took office December 6, 2004,

Hockfield is currently a corporate director of GE Industrial.

Key financial figures for GE Industrial

2007 Revenue: $17.7 billion

2007 Profit: 9% (%vol)

Number of Employees: ~70,000

In May 2007, GE acquired Smiths Aerospace for $4.8 billion.

The company is involved with Boeing’s KC-767[4] and F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, Lockheed Martin’s F-35 Lightning II, F-22 Raptor, and C-130J Hercules, and the Eurofighter Typhoon. Smiths engine components equip many major military and civil gas turbine engines, providing critical technologies from intake to exhaust.

GE is a multinational conglomerate headquartered in Fairfield, Connecticut. Its New York main offices are located at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in Rockefeller Center, known as the GE Building for the prominent GE logo on the roof. NBC’s headquarters and main studios are also located in the building. Through its RCA subsidiary, it has been associated with the Center since its construction in the 1930s.

The company describes itself as composed of a number of primary business units or “businesses.” Each unit is itself a vast enterprise, many of which would, even as a standalone company, rank in the Fortune 500 The list of GE businesses varies over time as the result of acquisitions, divestitures and reorganizations. GE’s tax return is the largest return filed in the United States; the 2005 return was approximately 24,000 pages when printed out, and 237 megabytes when submitted electronically

Pauvreté du Stimulus redux « Hady Ba’s weblog

[…] Photo […]

Nice interview. Confirms my view that Chomsky is often more sensible and down-to-earth than many of his biggest fans – a point also made well here – “Chomsky rubbishes Medialens?”:

http://wp.me/plVmg-ep