Foundations and Social Change: An Interview with Harry Browne On Corporate Power

Interviews, New in Ceasefire, On Corporate Power - Posted on Wednesday, June 20, 2012 15:00 - 1 Comment

Harry Browne braves the bitter cold for #OccupyUniversity #OccupyDameStreet, Dublin, Wednesday 30th November (source: boomingback.org)

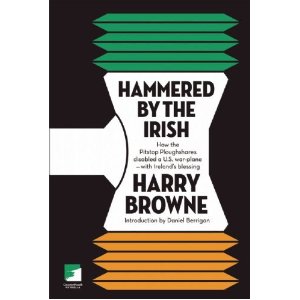

Harry Browne is a Lecturer in the School of Media, Dublin Institute of Technology, as well as an activist and journalist. He is the author of Hammered by the Irish: How the Pitstop Ploughshares Disable a US War-Plane – with Ireland’s Blessing (Counterpunch Books/AK Press, 2008). In 2010, Browne published an article titled “Foundation-Funded Journalism: Reasons to be Wary of Charitable Support” in the academic journal, Journalism Studies, and in March 2012 he published an abridged version of this piece in Counterpunch’s print newsletter.

Michael Barker (MB): Could you explain what you see as the main differences between hard and soft power?

Harry Browne (HB): I’m not a theorist in this area; my small research contribution has been to try to document a few examples of the working of philanthropic soft power in the journalism field. Soft power as I understand it is about winning consent from some target population rather than forcing it with violence or indeed payment. But I suppose in much of the practice of, say, international relations, or indeed industrial relations, the line between coercion and consent is not always absolutely easy to draw: it’s a spectrum rather than a binary.

MB: I tend to think that most writers have neglected emphasizing the importance of soft power, most specifically that of philanthropy, in legitimizing and extending capitalist relations: what are you thoughts on this matter?

HB: I think you’re right, though I think Perry Anderson, for example, has written brilliantly about the balancing act of force and consent in US foreign policy. But on the specific area of philanthropy, I was struck when I set off looking for some academic backup for my intrinsic suspicion of charitable foundations that the pickings were remarkably thin, though the work of someone like Robert Arnove has clearly been important for making a very small group of scholars feel they weren’t entirely crazy for considering the examination of foundation power a very worthwhile area of study, and indeed of polemic.

MB: When do you first remember reading or hearing about critiques of liberal philanthropists and their foundations? What was your initial reaction to such criticisms? Here I am predominantly thinking about the former “big three,” the Ford, Rockefeller and Carnegie foundations.

HB: I must say I think I was more or less born with the critique. I grew up in the US with activist parents and I seem to recall ‘foundation liberals’ as a term of abuse from as young as I can remember. But then my parents had the luxury of finding refuge for their politics in institutions that weren’t (then) reliant on foundation money: my mother in academia, my father in the Catholic church (as a priest) before moving on to academia. They could afford, in other words, independence from the big three, in a way that many people who slid from activism to NGO careers could not. Alexander Cockburn’s writing was also influential, starting in my teenage years, but it was pushing at an intellectual open door.

Another source that’s informed my thinking in this area in recent years is Doug Henwood, and through him Bob Fitch and his magnificent, dense book, The Assassination of New York, the model empirical study of how foundation power works with state and corporate power. The late Fitch is the author of a piece published in the Counterpunch print newsletter a few months ago that locates Obama brilliantly in that nexus — an article mentioned in Doug Henwood’s excellent tribute to Fitch.

MB: Following on from the last question, could you could briefly explain what you think about the academic/activist literature that is critical of liberal philanthropy?

HB: As I noted above, I was quite excited eventually to find it, much of it lurking in a single issue of the academic journal Critical Sociology. I cannot pretend to have exhaustively read in the field — as previously noted, I was seeking to find some intellectual supports for an empirical study, not to master this area theoretically. But what little I’ve read is very good and it must be frustrating that their arguments are not more widely repeated and adopted across the academic and activist left.

MB: How would you describe the general impact of liberal foundations on the evolution of research within universities and on intellectuals more generally?

MB: How would you describe the general impact of liberal foundations on the evolution of research within universities and on intellectuals more generally?

HB: This is beyond my ability to answer.

MB: Speaking about the issue more generally: can you think of any reasons why a discussion of the influence of capitalist philanthropy is generally excluded from the social sciences?

HB: The logic of academic life, in which advancement is so difficult and ‘research outputs’ so often measured in terms of capacity to win external funding — despite the fact that good research doesn’t necessarily require such funding — means that researchers must hesitate before they take on such a subject. I certainly did. There’s a nice quote from Bob Feldman I used in my own article, writing about the effects of foundation money on left-liberal journalism: “To document the degree [of the political influence] would require a massive research project unlikely to find funding.”

MB: Do you think anti-capitalist activists can strategically utilise liberal foundation funding to develop an anti-hegemonic movement for social change?

HB: My first instinct is to say of course not, and that if you’re getting such funding you ought to take a long look at yourself, because chances are your work is useless, or worse, for bringing about genuine social change. Then I remember the projects I’ve been involved in, with little bits of funding for practice and research from the likes of Rowntree, Atlantic and Carnegie. And I still have my doubts.

I have seen activists working with Rowntree funding in particular who I think are doing excellent work, both in the short term and toward ‘developing an anti-hegemonic movement for social change’. It would highly irresponsible and also insulting for me to cast aspersions at that work, or to assume that, say, state funding is inherently better, or worse for that matter. People who are currently gaining skills, building organisations and spreading knowledge on one or another of those teats may yet prove important in a transition to a better society. Like my Dad used to say, “Subvert and survive.”

But strategically, you ought to know and maintain the difference between why you do the work and why they fund it.

MB: Thank you for speaking to Ceasefire.

[…] Foundations for Social Change: An Interview with Harry Browne, Ceasefire Magazine, June 20, 2012. […]