Of Pink Ribbons and Philanthropy On Corporate Power

New in Ceasefire, On Corporate Power - Posted on Tuesday, April 3, 2012 12:00 - 1 Comment

Breast cancer is a critical issue and as such its causes need to be understood so that its toxic legacy can be laid to rest. Yet just as American women came out onto the streets to give voice to their discontent at Richard Nixon’s so-called ‘War on Cancer’, corporations responded in kind, seeking to force them back into quietude. Samantha King’s book Pink Ribbons, Inc.: Breast Cancer and the Politics of Philanthropy (University of Minnesota Press, 2008) consequently fulfills a vital role for all concerned citizens wishing to understand how corporate philanthropy — ostensibly in the service of cancer activism — has “helped fashion a far-reaching constriction of public life, of the meaning of citizenship and political action, and of notions of responsibility and generosity.”[1]

Consumption of “pink ribbon” merchandise has in many ways come to replace meaningful political engagement with the root causes of cancer. Feel-good celebration of survivorship in turn replaces righteous and much-needed politically targeted anger.

Money talks… and funding agencies (both nonprofit and for-profit) have exhibited a rather worrying, but entirely understandable, fixation on supporting “research that focuses on screening and treatment rather than prevention.”[2] With the terms of the funding debate for the Breast Cancer Movement adequately constricted, corporations have strived to undermine any effective grassroots political organizing that was taking place, overwhelming it with…

… an informal alliance of large corporations (particularly pharmaceutical companies, mammography equipment manufacturers, and cosmetics producers), major cancer charities, the state, and the media… National Breast Cancer Awareness Month (NBCAM), founded in 1985 by Zeneca (now AstraZeneca), a multinational pharmaceutical corporation and then subsidiary of Imperial Chemical Industries, is possibly the most highly visible and familiar manifestation of this alliance. AstraZeneca is the manufacturer of tamoxifen, the best-selling breast cancer drug, and until corporate reorganization in 2000 was under the auspices of Imperial Chemical, a leading producer of the carcinogenic herbicide acetochlor, as well as numerous chlorine and petroleum-based products that have been linked to breast cancer. (pp.xx-xxi)

In the form of strategic philanthropy, corporations have at their hands a highly sophisticated tool of social engineering. Rather than such corporate giving being a process that is deemed marginal to the business cycle, it is evident that this “highly calculated, measured, quantified, and planned approach to giving or ‘charitable investing’” has moved center-place into the profit-making nexus. In league with these philanthropic developments, grassroots political organising is apparently out, but “grassroots participation” is in vogue — “grassroots participation” being a “term increasingly used to describe individual consumption-based acts of philanthropy…”[3]

In the face of rising public anger, in the late 1970s apolitical walkathons were eagerly seized upon by the corporate-orientated cancer community as a safe stand-in for militant marches. And so, at the very moment that the nation’s poor and working class were under a vicious and sustained attack by the government, it was deemed appropriate by the newly emergent non-profit cancer establishment that personal fitness, not economic poverty, contributed most to the cancer epidemic.

With considerable assistance from the mass media, the government, in conjunction with the New Right and the Religious Right, engineered a national fantasy by which the effects of economic and social conditions (poverty and welfare “dependency”) were blamed on individual inadequacies or failings and the breakdown of the family. As scholars of this era have suggested, the “national preoccupation with the body” (Alan Ingham’s term), the rise of lifestyle politics, and the fitness boom can be understood both as ways to circumvent anxieties about the crisis of the “welfare state” and the family and as appeals to and celebrations of individualism and free will that were so central to the logic of Reaganism. (p.48)

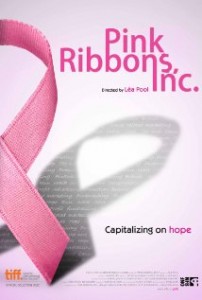

There has of course been much determined resistance to the corporate hijacking of the Breast Cancer Movement, with the “most prominent” example (highlighted by King), albeit foundation-supported, being Breast Cancer Action (BCA). In the past BCA has had a special focus on the activities of the Avon, a corporation which “has increasingly deployed philanthropy not merely to further some social good, but as a technique for market penetration and retention.”[4] So it is useful that BCA has just released a documentary based on King’s book titled Pink Ribbons, Inc (2012), whose script moves beyond the false hope offered by the hopelessly co-opted mainstream cancer movement.

Optimism of the will is important, but pessimism of the mind is especially critical if one is not to obscure the brutal reality of cancer in 21st century. Here one could look to the wise words of Audre Lorde, which she penned on March 30, 1979, and subsequently published in The Cancer Journals:

It was very important for me, after my mastectomy, to develop and encourage my own internal sense of power. I needed to rally my energies in such a way as to image myself as a fighter resisting rather than as a passive victim suffering. At all times, it felt crucial to me that I make a conscious commitment to survival. It is physically important for me to be loving my life rather than to be mourning my breast. I believe it is this love of my life and my self, and the careful tending of that love which was done by women who love and support me, which has been largely responsible for my strong and healthy recovery from the effects of mastectomy. But a clear distinction must be made between this affirmation of self and the superficial farce of “looking on the bright side of things.” Like superficial spirituality, looking on the bright side of things is a euphemism used for obscuring certain realities of life, the open consideration of which might prove threatening or dangerous to the status quo. (p.101)

Lorde was “able to argue for the need for self-affirmation among women with the disease and, at the same time, engage critically with a number of issues rarely mentioned in contemporary mainstream discourse” not least of which was the presence of the cancer-industrial complex. Her emancipatory story stands in stark contrast to mainstream cancer narratives, which over the past two decades, have actively constructed breast cancer “as a unifying issue that is somehow beyond the realm of politics, conflict, or power relations.”[5]

Narrowly focused single-issue organising — a long-standing favourite of the corporate foundation world — will not suffice for any citizen genuinely concerned about organised political change: especially if the root causes of breast cancer and women’s suffering are to be adequately addressed. Indeed, in the past “such a singular focus prevents activists, policy makers, the media, and the public at large from understanding questions of health and illness in the larger context from which they arise.”[6] This need not and must not remain the case.

Narrowly focused single-issue organising — a long-standing favourite of the corporate foundation world — will not suffice for any citizen genuinely concerned about organised political change: especially if the root causes of breast cancer and women’s suffering are to be adequately addressed. Indeed, in the past “such a singular focus prevents activists, policy makers, the media, and the public at large from understanding questions of health and illness in the larger context from which they arise.”[6] This need not and must not remain the case.

Pink Ribbons, Inc. Breast Cancer and the Politics of Philanthropy

Samantha King

208 pages

University of Minnesota Press (2008)

[…] Of Pink Ribbons and Philanthropy, Ceasefire Magazine, April 3, 2012. […]