Bobby Fischer : World Championship Candidate Chess Corner

Chess Corner, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, January 5, 2012 13:26 - 2 Comments

By Paul Lam

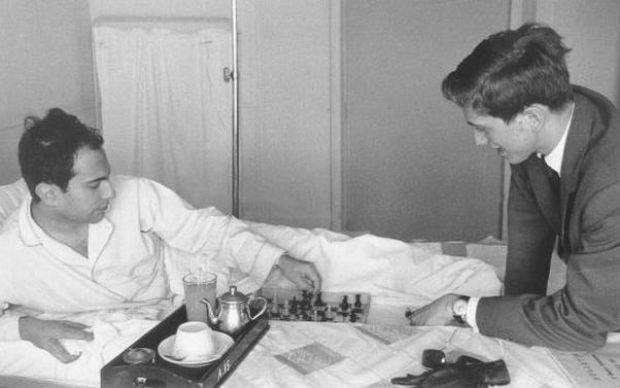

“When Mikhail Tal fell ill, Fischer was the only player who visited him in hospital, a gesture which touched Tal deeply, giving rise to the iconic photo of the two playing chess on Tal’s hospital bed.”

In 1959, the year after his triumphant entry onto the international chess stage, a sixteen year old Bobby Fischer was primed for the Candidates Tournament and an opportunity to win the right to challenge the World Chess Champion, Mikhail Botvinnik. True to form, Fischer indulged the press with some outrageously insulting remarks about his fellow competitors leading up to the tournament.

Despite the bluster, however, it was clear that Fischer, notwithstanding his prodigious achievements to date, was not yet strong enough to meaningfully threaten the Soviet stranglehold on chess. His run-in with the eventual winner, Mikhail Tal, who would go on to dethrone Botvinnik, was an emphatic case in point, as Fischer received a stern lesson from the ‘Magician from Riga’ and lost all four of the games they played. Nevertheless, Fischer was still able to put in a respectable performance overall, finishing with 12.5/28 in joint fifth with Svetozar Gligoric.

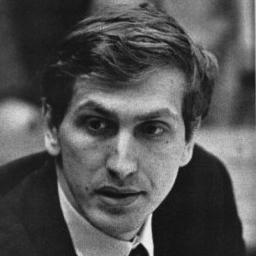

The start of the new decade also coincided with Fischer’s transformation from a gauche, fashion-oblivious teenager to a well-dressed, striking figure; tall, broad-shouldered and handsome. Out went the T-shirts, shorts and sneakers; in came expensive hand-tailored suits. Anyone who might have assumed that this change in appearance was a sign of new-found maturity was mistaken. Having never held formal education in high regard, Fischer had left school early to pursue life as a professional chess player. His relationship with his mother had deteriorated, in spite of her unrelenting support for his chess career, and he would soon become permanently estranged from her. With few friends other than those he had met through chess, when not playing he spent most of his days absorbed in study of the game.

At Buenos Aires in 1960, Fischer suffered what would prove to be his worst ever tournament result, finishing in thirteenth place. Amidst speculation over the reasons for this uncharacteristically poor performance, it was alleged that fellow American Grandmaster Larry Evans, who would go on to become Fischer’s trainer and a key mentor, had introduced his younger, sexually inexperienced compatriot to a local woman during the tournament. Off-the-board distractions or not, almost immediately following this disaster he bounced back with a fine performance at the 1960 Chess Olympiad, scoring 11/17 on top board for the US.

In 1961, he played a match against his main domestic rival, Samuel Reshevsky, who was determined to prove that he was still the King of American chess. During the match, with scores even at 5.5 each, game twelve was rescheduled from 1.30 pm to 11.00 am. Incensed at the perceived lack of respect and being forced to play at a time which did not suit him, Fischer withdrew from the match, leaving Reshevsky the winner by default. In the same year, he gave a now notorious interview to the journalist Ralph Ginzburg, in which, among other things, he described women as ‘weak’, ‘stupid’ and unable to play chess, referred to Botvinnik as a ‘Russian patzer’, complained that there were too many Jews in chess (despite his own mother being Jewish), and claimed that he broke contact with his mother because she ‘keeps in my hair’.

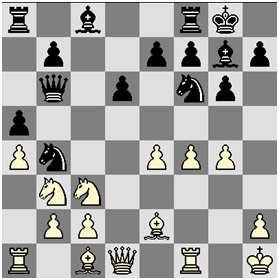

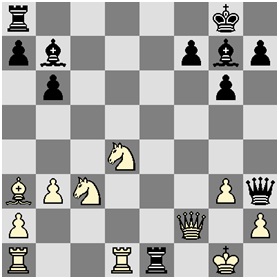

Fischer – Korchnoi, Curacao 1962

At the beginning of 1962, Fischer achieved his finest tournament result to date. He won the Stockholm Interzonal with a dominating performance of 17.5/22, 2.5 points ahead of his closest rivals Efim Geller and Tigran Petrosian, again qualifying for the Candidates Tournament. Unlike three years previously, Fischer was now a clear favourite to win the tournament and earn the right to play for the World Championship. However, what followed, in the tropical haven of Curacao, was nothing less than a calamity, as Fischer, intoxicated by hubris, suffered a major reversal of fortune.

At the beginning of 1962, Fischer achieved his finest tournament result to date. He won the Stockholm Interzonal with a dominating performance of 17.5/22, 2.5 points ahead of his closest rivals Efim Geller and Tigran Petrosian, again qualifying for the Candidates Tournament. Unlike three years previously, Fischer was now a clear favourite to win the tournament and earn the right to play for the World Championship. However, what followed, in the tropical haven of Curacao, was nothing less than a calamity, as Fischer, intoxicated by hubris, suffered a major reversal of fortune.

In the above position, Fischer lashed out recklessly with 13.g4?, allowing Korchnoi to play a combination which irreparably ruined his position.

13…Bxg4! 14.Bxg4 Nxg4 15.Qxg4 Nxc2 16.Nb5 Nxa1 17.Nxa1 Qc6

13…Bxg4! 14.Bxg4 Nxg4 15.Qxg4 Nxc2 16.Nb5 Nxa1 17.Nxa1 Qc6

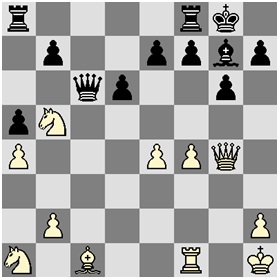

The damage done is clear to see. Fischer’s king has been left exposed and his pieces reduced to feeble entities with their lines of communication shattered. Against a player of Korchnoi’s class, the result is now a foregone conclusion, and the ‘Leningrad Lip’ proceeded to end matters on move 32.

An out-of-form Fischer eventually finished in fourth place, 3.5 points behind the winner, Petrosian. The outcome was a deeply bitter pill for him to swallow and his instinctive reaction was to accuse the Soviets of conspiring against him to deny him victory, solidifying his reputation as the least gracious of bad losers.

Fischer’s undignified behaviour post-Curacao contrasted with one incident that occurred during the tournament. Mikhail Tal, who was to be dogged relentlessly by poor health throughout his life, had fallen seriously ill with kidney problems and been forced to withdraw before the Candidates had yet ended. Tal, a charismatic, amiable character of Bohemian outlook on and off the board, was Fischer’s polar opposite in many ways. Yet when Tal fell ill, Fischer was the only player who visited him in hospital, a gesture which touched Tal deeply, giving rise to a now famous photo showing the two playing chess on Tal’s hospital bed.

When Fischer wrote an article for Sports Illustrated later that year titled ‘How the Russians fixed World Chess’, only Tal was exonerated. Arguably, Fischer’s drubbing at the hands of Tal in the 1959 Candidates Tournament had left him with a healthy respect for his great contemporary; a rare, perhaps the unlikeliest, quality for Fischer to demonstrate.

Fischer’s second reaction to the Curacao calamity was to effectively withdraw from international chess for the next two years in protest. On the domestic front, however, he remained as dominant as ever. In the 1963 US Chess Championship, he recorded one of the greatest tournament scores of all time: a perfect 11/11 against the cream of American chess talent.

Fischer proved simply unstoppable, as he swept aside all opposition. As fate would have it, his coup de grace came in his game against Robert Byrne, the elder brother of Donald who had lost the ‘Game of the Century’ to the thirteen year-old-Fischer. Although Fischer was a clear favourite, no-one before the game could have expected a pushover. In addition to being a stronger player than his brother, Byrne had never lost to Fischer before. On the day though, Fischer’s play was inspired.

Fischer proved simply unstoppable, as he swept aside all opposition. As fate would have it, his coup de grace came in his game against Robert Byrne, the elder brother of Donald who had lost the ‘Game of the Century’ to the thirteen year-old-Fischer. Although Fischer was a clear favourite, no-one before the game could have expected a pushover. In addition to being a stronger player than his brother, Byrne had never lost to Fischer before. On the day though, Fischer’s play was inspired.

5.cxd5 cxd5 6.Nc3 Bg7 7.e3 0–0 8.Nge2 Nc6 9.0–0 b6 10.b3 Ba6 11.Ba3 Re8 12.Qd2 e5!

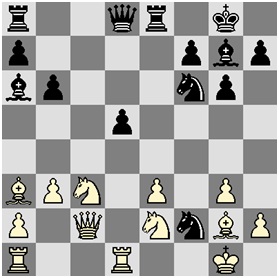

R. Byrne – Fischer, US Championship, New York 1963

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.g3 c6 4.Bg2 d5

Fischer plays his pet Grunfeld Defence, as he did against the younger Byrne brother in 1957.

Byrne has played a rather sedate variation and Fischer now takes advantage by striking out in the centre. He has judged correctly that his piece activity will compensate for the isolated queen’s pawn.

Byrne has played a rather sedate variation and Fischer now takes advantage by striking out in the centre. He has judged correctly that his piece activity will compensate for the isolated queen’s pawn.

13.dxe5 Nxe5 14.Rfd1 Nd3 15.Qc2 Nxf2!

Ripping open the kingside defence.

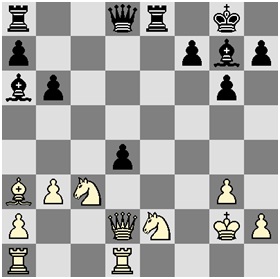

16.Kxf2 Ng4+ 17.Kg1 Nxe3 18.Qd2 Nxg2!

Superb. Black shuns materialism and instead decides to eliminate another kingside defender, leaving the White king further weakened.

19.Kxg2 d4!

19.Kxg2 d4!

Opening up the h1-a8 diagonal for Black’s light-squared bishop to have maximum impact

20.Nxd4 Bb7+ 21.Kf1 Qd7 0-1

White’s resignation is not premature. However, it does deny a beautiful finish. After 22.Qf2 Qh3+ 23.Kg1, Black has the incredible 23…Re1!!, perhaps the greatest move never played.

If 24.Qxe1 then Qg2 mate follows, or 24.Rxe1 Bxd4 with White again facing dire consequences.

In 1965, Fischer made his much-awaited return to international chess.  He finished joint-second at the Capablanca Memorial held in Cuba, despite being in the curious position of not being able to set foot on the island due to the poor relations between Cuba and the US. Instead, he played from New York City, with his moves being messaged to Cuba by telex.

He finished joint-second at the Capablanca Memorial held in Cuba, despite being in the curious position of not being able to set foot on the island due to the poor relations between Cuba and the US. Instead, he played from New York City, with his moves being messaged to Cuba by telex.

In 1966 he finished second to Soviet Grandmaster Boris Spassky in the Piatagorsky Cup, an encounter foreshadowing future momentous events. The same year he won the US Championship again and repeated this triumph in 1967. That year, in the Sousse Interzonal, he started like a train and, with 8.5/10, looked to be inexorably roaring towards victory and the Candidates Matches. Once again however, Fischer’s intransigence intervened to bring his participation to a premature end.

Having become involved with the Worldwide Church of God, an evangelical sect, he refused to play games on the Sabbath, leading to a scheduling dispute with the tournament organisers. An indignant Fischer withdrew from the tournament and began another self-imposed exile from chess. He did however use the time to write a book, ‘My 60 Memorable Games’, published in 1969, which received much praise and which to this day is regarded as a classic of chess literature.

In 1970 Fischer surprised the chess world by returning to play in the USSR v the Rest of the World match after a year and half of not playing any serious chess. Despite this lack of match practice, members of the Rest of the World team were keen for his presence, believing that they wouldn’t stand a chance against the Soviets otherwise. However, given Fischer’s by now well-known temperamental nature and his unyielding loyalty to his own principles, the team organisers were apprehensive.

In 1970 Fischer surprised the chess world by returning to play in the USSR v the Rest of the World match after a year and half of not playing any serious chess. Despite this lack of match practice, members of the Rest of the World team were keen for his presence, believing that they wouldn’t stand a chance against the Soviets otherwise. However, given Fischer’s by now well-known temperamental nature and his unyielding loyalty to his own principles, the team organisers were apprehensive.

To complicate matters, the Danish Grandmaster, Bent Larsen, who had won tournament after tournament during Fischer’s absence, establishing himself as arguably the best non-Soviet player in the world, insisted that he play board 1 for the Rest of the World.

Negotiations for Fischer’s participation look doomed to failure until Fischer astounded everybody by declaring that he was happy to play second board to Larsen. It was a hitherto unthinkable act of sportsmanship, and the chess world celebrated in response. Bobby was back. In the ensuing ‘Match of the Century’, Fischer played superbly, beating Petrosian 3-1, and nearly helped the Rest of the World to victory, as the Soviets emerged winners by the narrowest of margins: 20.5 to 19.5 points.

Fischer had proven his point resoundingly. No-one could now doubt that he, not Larsen, had deserved the top spot. The World Championship, held by Boris Spassky, remained the only accolade still outside his grasp. It was now everyone’s expectation that he would play for the right to wrestle the World Championship from Soviet control. The dream match, once a distant prospect, seemed closer to reality than ever.

2 Comments

Leon

Lucas Peres

Thank you!!! Nice post.

(Chess Brasil)

Thankyou, delightful piece 🙂