Chess Corner Return of the Romantic

Arts & Culture, Features, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, June 28, 2011 10:00 - 2 Comments

Howard Staunton and Bernhard Horwitz

By Paul Lam

The ‘Romantic’ age of chess, which spanned most of the nineteenth century, is a period that generations of chess-players have looked back upon with great nostalgia, not only for the spectacular chess that it produced, but for the Bohemian outlook and lifestyle that prevailed at the time. If there ever was a time when chess was sexy, this was certainly it.

Chess was certainly considered no respectable pursuit, let alone a way to earn a living. The conduct of chess-masters of the Romantic period could hardly have dispelled such a notion, for it frequently verged on the kind of behaviour that would have raised eyebrows on the set of an Oliver Reed film.

There were exceptions, such as Howard Staunton-widely regarded as Britain’s best player of the first half of the nineteenth century-a quintessential English gentleman who edited a collection of Shakespeare’s plays.

For the most part however, chess-masters of the time were as likely to be spending their time womanising, fighting duels or in absinthe-induced stupors as they were to be creating fire on the chequered board (or sometimes two or more simultaneously, it must be surmised).

The coffee-house was the refuge of the nineteenth-century master, but the local brothel often provided alternative residence. No wonder that professional chess-players were seen at the time as being little better than gamblers and fellow-travellers of the lumpenproletariat.

The colourful and hedonistic lives of our great predecessors are a world away from the staid image that dogs the modern game. No wonder we yearn for the days of old. Perhaps chess-players are simply repressed people; reduced to fulfilling our fantasies on the board which is our only outlet for satisfaction; a form of mental masturbation.

I only say this half in jest, for there is a sense in which the moves we play over the board continue to sustain an appreciable link with the glorious past. It may not be advisable to transpose the vigour with which the Romantics played out their libertine lifestyles to our present everyday lives, but we can certainly transpose it to our pieces. The likes of Howard Staunton, Adolf Anderssen and Paul Morphy are long dead, but the brilliancies that they produced over the board continue to inspire chess-players right up to the present day.

Furthermore, there is a sense in which we feel a real connection with the spirit of great players of the past through the moves that they played. In this respect, the spirits of Staunton, Anderssen and Morphy are very much alive. Every time we play the openings of old, in the intended spirit of the opening as conceived by the Romantic masters, we can still feel the original energy bursting through.

We may not be able to resurrect the Romantic Age, but we can certainly relive the spirit of the era through the chess that we play. The following game is testament to the spirit of Romanticism which lives on today:

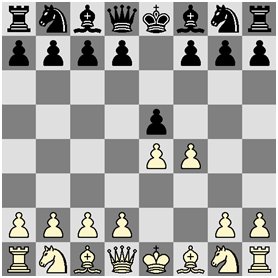

Anderssen-Kieseritzky, London, 1851

1.e4 e5 2.f4 The King’s Gambit was by far the most popular opening of the Romantic Age. White sacrifices a pawn to gain greater central control and opens up the f-file, creating attacking prospects against the Black King.

2…exf4 3.Bc4 The King’s Bishop’s Gambit. Today, 3.Nf3 is preferred and is undoubtedly the superior move.

3…Qh4+4.Kf1 White loses the right to castle and his king is exposed, but Black lags behind in the development and his Queen is prone to attack.

4…b5 An imaginative but unsound counter-gambit. Counter-gambits are usually played with the intention of catching up on development. The irony is that the complete opposite happens here!

5.Bxb5 Nf6 6.Nf3 Qh6 Black’s Queen is already looking rather silly.

7.d3 Nh5 8.Nh4 Qg5 Three of Black’s first 8 moves have been with the same piece.

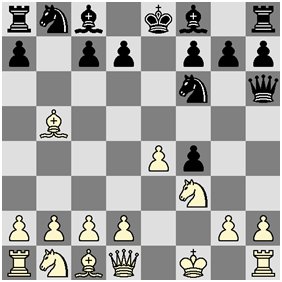

9.Nf5 c6 10.g4 Nf6 11.Rg1! Excellent judgment. White offers a piece in return for development with tempo and Black greedily obliges.

11…cxb5 12.h4 Qg6 13.h5 Qg5 14.Qf3 Ng8 A miserable concession

15.Bxf4 Developing with tempo

15…Qf6 16.Nc3 White has virtually completed his development, while most of Black’s pieces are asleep.

16…Bc5 17.Nd5! Another sacrifice as the White knight makes a heroic leap into the dominant d5-square, ominously nearing the Black King.

17…Qxb2 18.Bd6! Now White offers a whole rook in exchange for bringing his dark-squared bishop into the fray

18…Bxg1 19.e5! The sacrifices keep coming. This move sacrifices the other rook, but cuts the line of communication between the Black Queen and her beleaguered King.

19…Qxa1+ 20.Ke2 Na6 21.Nxg7+ Kd8 22.Qf6+! A final sacrifice, diverting the Black knight from the defence of the vital e7 square, thus forcing mate. Appropriately it is the White Lady, the most powerful piece on the board, who gives up her life to deliver the coup de grace.

22…Nxf6 23.Be7# 1-0 White has sacrificed nearly all his pieces, yet it is the Black King who faces the ignominy of mate.

The Romantic Age of chess was epitomised in the play of Adolf Anderssen, regarded as the greatest player of his time before the rise of Morphy. His games were characterised by tactics galore, dashing attacks, dazzling sacrifices and general disregard for positional principles.

The marvellous effort above was crowned the ‘Immortal Game’, and it is fair to say that playing through it continues to excite and delight players today, myself included. That said, Black’s play in the game leaves much to be desired.

The marvellous effort above was crowned the ‘Immortal Game’, and it is fair to say that playing through it continues to excite and delight players today, myself included. That said, Black’s play in the game leaves much to be desired.

Some explanation is required here. In accordance with the bold, cavalier style of play at the time, declining a gambit was regarded as an act of unforgivable cowardice and a breach of fundamental Romantic chess etiquette. The Immortal Game is an aesthetic gem on the part of Anderssen, but only because Kiesertizky was so co-operative.

And Kieseritzky was no mug either, one of the strongest players of the nineteenth century in fact. Yet even amateur players today might afford themselves a guffaw or two at how weakly Black played in this game.

The wistfulness that we feel towards the Romantic Age is thus somewhat tempered by smugness in our superior knowledge as we smile wryly at the shortcomings of our great predecessors.

The emergency of Wilhelm Steinitz, the first official World Champion, in the latter half of the nineteenth century is seen as signalling the decline of the Romantic era of chess. Steinitz, like most of his contemporaries, was a committed classical player, but based his play on solid positional foundations.

By the time of the Hypermodernist revolution, few leading players still clung to the Romantic ideal. One noted exception was the Austrian master Rudolf Spielmann, dubbed the ‘Last Knight of the King’s Gambit’.

However the Romantic Ideal never really died so much as fade into the background. Occasionally, great players of later generations were intrepid enough to test Romantic chess at the very highest level.

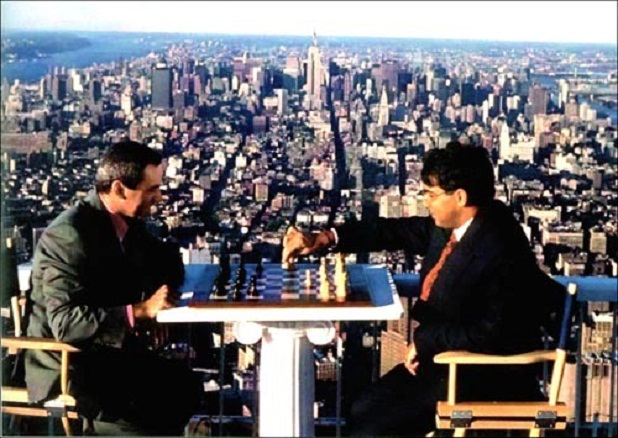

Like Anderssen a century before him, the young Boris Spassky, the tenth World Chess Champion, favoured the King’s Gambit. The following game became so famous that the final position featured in the 1963 James Bond film ‘From Russia With Love’.

Spassky-Bronstein, USSR Championship, Leningrad, 1960

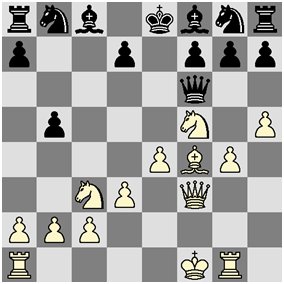

1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3 d5 4.exd5 Bd6 5.Nc3 Ne7 6.d4 0-0 7.Bd3 Nd7 8.0-0 h6 9.Ne4 Nxd5 10.c4 Ne3 11.Bxe3 fxe3 12.c5 Be7 13.Bc2 Re8 14.Qd3 e2 15.Nd6!! Undoubtedly one of the greatest moves of all time.

15…Nf8. 16.Nxf7 exf1=Q+ 17.Rxf1 Bf5 18.Qxf5 Qd7 19.Qf4 Bf6 20.N3e5 Qe7 21.Bb3 Bxe5+ 22.Nxe5+ Kh7 23.Qe4+1-0

Half a century on from this masterpiece in miniature, Romantic chess is still very much alive, despite the advances that have been made. As I have elaborated on in previous columns, chess has changed hugely in the last century. Some might say that we live in a post-Hypermodernist age. The tree of opening theory continues to grow inexorably in all directions. Above all, positional understanding has developed hugely since the days of Anderssen and the Immortal Game.

Nevertheless, it seems that each generation of great players continues to produce a few brave souls, willing to disregard the modern orthodoxy. Occasionally they are rewarded spectacularly. No less a player than Kasparov was responsible for the rejuvenation of an opening that many felt had been consigned to the annals of history. And just look at the level of opposition.

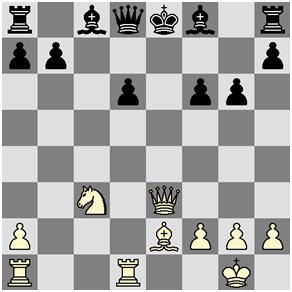

Kasparov-Anand, Tal Memorial, Riga, 1995

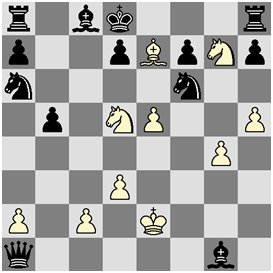

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.b4 Yarrrr!! So it’s an Evans Gambit! The eponymous seafaring Captain Evans was the first to play this opening, in the early-nineteenth century. What is the World Champion doing fooling around with this relic of a bygone swashbuckling era? The idea is that by sacrificing the b4-pawn, White will gain tempo by attacking the Bishop with c3, followed with the construction of a pawn centre with d4. With open lines and good opportunities for development, White hopes to catch Black in a whirlwind attack right out of the opening.

4…Bxb4 5.c3 Be7 6.d4 Na5 7.Be2 exd4 8.Qxd4 Nf6 9.e5 Nc6 10.Qh4 Nd5 11.Qg3 g6 12.O-O Nb6 13.c4 d6 14.Rd1 Nd7 15.Bh6 Preventing the Black King from castling to safety. Black’s position is already looking very awkward.

15…Ncxe5 16.Nxe5 Nxe5 17.Nc3 f6 18.c5 Nf7 19.cxd6 cxd6 20.Qe3 Nxh6 21.Qxh6 Bf8 22.Qe3+ Compare the position with Anderssen-Kieseritzky. Black is materially superior, but his development is feeble and his pawn structure is wrecked.

22…Kf7 23.Nd5 Be6 24.Nf4 Qe7 25.Re1 1-0 And Anand resigns after only twenty-five moves! Ruinous loss of material is unavoidable. The pin on the Bishop and accompanying threats are too much to bear.

Romantic chess is great fun to play. But you don’t just have to be a daredevil, looking to create tactical complications and exciting positions at any cost. Romantic chess can be winning chess too.

More recently, twenty-year-old wunderkind Magnus Carlsen, already the second strongest player of all time after Kasparov, played the King’s Gambit in a game against fellow super-GM Wang Yue and won convincingly. However, it was not so much of a sparkling tactical performance as a mature positional display. So, Romantic openings do have another dimension to them that can accommodate the modern requirements of the game.

Britain’s number two player, former World Championship finalist Nigel Short, has also dabbled successfully with openings hailing from the Romantic Age. The Max Lange Attack (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc4 4.0-0 Nf6 5.d4 exd4 6.e5), named after the nineteenth-century German master, is as old as the hills but still deadly as Laurent Fressinet found to his cost. The French super-GM, playing Black against the Englishman in the 2010 Chess Olympiad, found himself with his King on g6 on move 11 and eventually succumbed after 29 moves to a vicious attack.

Romantic chess offers you the opportunity to play exciting, dashing, daring chess with the added bonus of surprise-value. It’s a great way to hone your tactical sharpness and win your games in style. You certainly won’t get the quiet life, but if you’re partial to an adrenaline-pumping high, then it may just be for you. And let’s be frank, if it’s good enough for Kasparov, Carlsen and Short, it’s certainly good enough for you and me! Good luck swashbuckling!

Solution to previous puzzle: 17.Rb6+! is decisive. If 17…Nxb6, then 18.Nf6+ and mate on d8 to follow.

Paul Lam, a law graduate is Ceasefire‘s chess columnist. He is an internationally rated chess-player and was one of England’s leading junior players, representing the national team in Estonia and the Czech Republic. His column appears every other week.

2 Comments

Chess Corner – Return of the Romantic – Ceasefire Magazine | Chess IQ

Chess Corner Return of the Romantic – Ceasefire Magazine | Chess IQ

[…] the original: Chess Corner Return of the Romantic – Ceasefire Magazine Filed Under: Chess, General Tagged With: chess, great-nostalgia, nineteenth, spectacular, […]

[…] the original post: Chess Corner – Return of the Romantic – Ceasefire Magazine Filed Under: Chess, General Tagged With: chess, great-nostalgia, nineteenth, spectacular, […]