Brazil: Anatomy of a Crisis Beautiful Transgressions

Beautiful Transgressions, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Wednesday, July 10, 2013 17:15 - 3 Comments

By Sara Motta

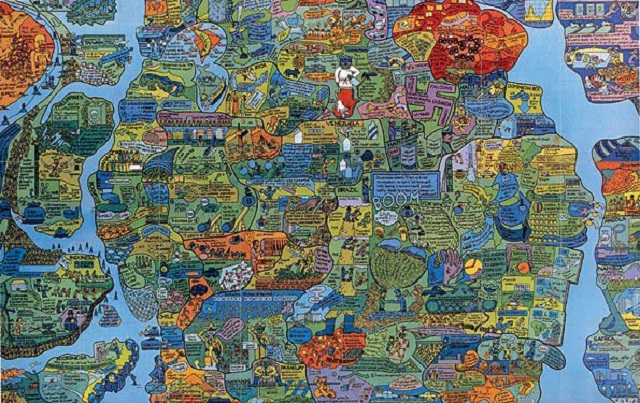

Öyvind Fahlström, ‘Sketch for World Map Part 1 (Americas, Pacific)’

For over two weeks in late June/early July hundreds of thousands protested in more than a hundred cities across Brazil amidst incidents of police brutality and increasing governmental crisis. What is happening in one of Latin America’s economic and political ‘success’ stories?

‘Politics as normal’ is no longer able to contain the needs, desires and hopes of large sections of Brazilian society. The fault-lines of neo-liberalism ‘with a human face’ are rupturing with the emergence of new, contradictory and hybrid political subjects and political horizons.

Yet from the shadows can be deciphered the contours of a reimagined emancipatory left of the 21st Century, quintessentially Brazilian, mirroring practices across Latin America and beyond.

The immediate spark of the protests was an increase in public transport costs in Sao Paulo. Protests have mushroomed against spiralling government spending for next year`s football World Cup and the 2016 Olympics amidst a deterioration in public services, urban life and working conditions for the majority. Common to all was disillusion with, and anger against, corruption in politics, the media and the police.

While there is general agreement about the significance of the protests commentators are divided in their analyses of their nature. Two important perspectives are those that warn of the fragmentation and political disorganisation of the protests and argue for political and intellectual leadership and those that argue they represent the emergence of autonomous politics beyond and against parties, government and the state .The first perspective emerges from traditions of representational left politics whilst the latter from post-1968 autonomous politics.

Yet Brazil’s distinct history of left politics, both in its parties and social movements creates a situation of hybridity and multiplicity in popular political traditions, practices and horizons.

Brazil thus presents a challenge to this political debate since its experiences and struggles cannot be fitted nearly into the political categories deriving from either dominant 20th century left practices or purely autonomous politics.

Key to contextualising the multiple voices that are emerging is an understanding of the current governing party, the Workers’ Party’s relationship with the popular classes, more specifically the formal and informal working classes.

As in the cases of the modernisation of the British Labour Party, the Chilean Socialist Party, the Australian Labour Party (the list goes on), it is the institutional left who have played a key role in disarticulating the popular subjects of the dominant social-cultural matrix of the 20th Century left. In this organized labour was viewed as the key agent of popular struggle, the state and party as the key political tools of social transformation and the place of work the key site of political organisation.

The PT’s election to power in late 2002 under their emblematic leader Luiz Ignacio “Lula” Da Silva for many represented hopes that neoliberalism would be challenged and a new more popular, participatory and inclusive model of development and democracy fostered.

However, the Lula Governments and now that of his chosen successor Dilma Roussef, held a trump political card (that their predecessors from the traditional political elites lacked), which enabled them to stabilise neoliberalism in Brazil for over a decade – their relationship with Brazil’s organised popular classes.

The PT emerged from the popular democratisation and union struggles of the late 1970s and 1980s. Many of its left tendencies and militants were both party members and movement organisers. More radical PT local and regional governments had developed novel experiences of participatory government.

This context fostered historic, symbolic and affective relationships with those popular sectors traditionally associated with the left. Thus when Lula issued his Carta (Letter to the Brazilian People) during the 2002 election campaign which committed any future PT government to maintaining the macroeconomic framework of neoliberalism many PT militants, Left organisations and movements such as the movimento dos trabalhadores rurais sem terra (MST) were torn between feelings of betrayal and loyalty.

This shaped their political relationships with the PT governments which have been characterised by uncertainty and relative demobilisation.

Predictably, once elected, whilst making formal concessions to the solidarity economy movement, the MST and in sectors such as education, the overall economic, political and social strategy of the government mirrored its third way neoliberal brothers in countries such as Chile, the UK and Australia.

The government fostered alliances through subsidies, tax breaks and informal and formal institutional relationships with transnational finance and transnational agri-business at the expense of providing the conditions for a universalisation of health, education, housing and livelihood.

The resultant rapid and extensive growth of agri-business was particularly intense in the northeastern states of Rio Grande do Norte, Bahia, Pernambuca and Ceará. This created a new actor in the rural context: the agroindustry worker whose conditions of work were often unregulated, degrading and precarious.

Such a strategy of accumulation through dispossession has resulted in peasants and communities being thrown off their land, the destruction of life and ecosystems and increasing social inequalities.

And despite historic ties between the PT and the MST, agrarian reform remained a promise as opposed to a reality. Yet because of these histories of struggles and solidarities the MST refrained from intensifying oppositionary mobilisation. Sandra Gadelha, activist academic and popular educator expresses some of the complexity of this popular political terrain when she reflects that “Lula and the PT governments have represented themselves as the ‘father of the MST’ whilst acting as the ‘mother of agro-business”

In the realm of the state the PT leadership governed more with the traditional political classes, through informal political bargaining, than with its own party and militancy. They actively disarticulated potential internal dissent by for example expelling dissident senators who voted against the neoliberal reform of public sector pensions.

The PT’s governing practices reproduced the historic de-democratisaton of the Brazilian state and political elite and the exclusion of the popular sectors, particularly noticeable in ministries related to economic policy making, from political power.

These processes were also mirrored in internal party politics. The bureaucratised leadership and dominant tendencies such as Articulação concentrated political power in terms of appointments of candidates and the making of significant political decisions and hollowed out party education and organising in the grassroots.

The logics of de-democratisation and pursuit of power meant that no consistent political work was done to connect the party with the new generations of youth promised democracy, development and a say in politics, and yet surrounded by continuing inequalities, deteriorating public services and a continent in multiple uprisings.

Paradoxically the party was able to govern but at the expense of the consolidation of an institutionalised party apparatus and militancy. Dominated by the logics of power, they undercut the institutional moorings of their historical left identities and practices.

Some of this delinking from its historic roots expressed itself in disillusionment and disarticulation. Yet it was also responded to with an attempt at political re-articulation through the public split from the party in 2005 of intellectuals, left militants and tendencies to form Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (PSOL).

The PT’s strategy disarticulated, disappointed and/or coopted popular class militancy and was unable to articulate political relationships with youth, creating elements of the crisis of representation the political elites’ ( of which the PT is a part) are currently facing.

The second key element in the anatomy of the current crisis is the PT’s relationship with the informal working classes. True to the dominant (but not only) ideological moorings of the PT in the hegemonic traditions of 20th century left politics, they have historically focused their political attentions on the formal popular classes.

In the context of dependent development of Brazil, in which the informal working classes in most regions made up the majority of the working classes, this strategy reproduced the historic political fragmentation of, and divisions within, Brazil’s popular classes. This undercut the party’s ability to come to power on a counter-hegemonic anti-neoliberal agenda in the elections of 1989, 1994 and 1998.

In government the PT developed a strategy that depoliticised and individualised social policy to the Brazilian poor. Key to this is Bolsa Familia – a targeted conditional transfer of funds – highly praised by the World Bank that has its greatest distribution in the northeast.

Whilst reducing absolute poverty this had no intention of creating universal public services, but rather disciplinary social policy mechanisms which maintain the fragmented and individualized relationships of the informal popular classes with the state (and the PT as the democratic face of a neoliberal disciplinary state).

Yet here perhaps is the Achilles’ heel of the story of the Workers’ Party’s marriage with neoliberalism. Targeted, conditional money transfers do not create the cultural, institutional or affective relationships of loyalty, solidarity and commitment that do sustained political organising and articulation.

Whilst enabling the winning of votes, this support is conditional and does not provide a guaranteed popular base for the continued stability of PT governments and the neoliberal coalition of economic and political elites.

Thus the losers of the PT’s marriage with neoliberalism are multiple: the organised working class, public sector workers, left militants, peasant and indigenous communities, youth, and despite Bolsa Familia, the informal sectors.

It is these sectors who rebelled and mobilised in the streets. And of course as these actors are multiple so are their histories, subjectivities, desires and political horizons.

For whilst the PT governments have consolidated their marriage with neoliberalism, deepened their separation from their historic support base and developed social and economic policy that disarticulates the conditions for the development of a new popular left politics, such processes have not been experienced passively. Communities and workers have continued to mobilise, organise and visualise alternatives.

The MST, one of the biggest social movements in Latin America, despite its uneasy and restrained relationship with the PT governments has continued to mobilise for agrarian reform. Their understanding of agrarian reform involves much more than a legal redistribution of land. The MST seeks the democratisation of Brazilian society at the political, economic, cultural levels through the self-organisation of the popular classes.

Thus MST communities develop agricultural production which has community need and sustainability at their heart. Community production is self-organised, embedded in cultural and spiritual traditions and structures of feeling and actualised through the development of autonomous forms of education such as educacão do campo.

In the cracks of the contradictions of the PT governments the MST has continued to build the self-organising capacity of rural landless workers.

The solidarity economy movement has also continued to grow and again despite internal heterogeneity and am ambiguous relationship with the government there is a powerful transformatory tendency. For this transformatory tendency the solidarity economy is as Marcus Arruda radical philosopher and educator explains ‘an ethical, reciprocal and cooperative form of consumption, production, exchange, finance, communication, education, development that promotes a new way of thinking and living’.

Particularly strong amongst the female urban poor, the practices and projects of the solidarity economy have built the self-organising capacity of urban excluded informal workers.

And significantly the communities dispossessed by the huge dam organise, collectivise and fight for their right to ecologically sustainable forms of popular development. In the case of Ceará the Movimento 21 has formed bringing together local communities, radical lawyers, scientists, popular educators, the MST and the PSOL.

These experiences are influenced by the rich traditions of liberation theology and popular education that emerged in the 1960s and by the emergence and development of the PT.

The former traditions create a popular cultural inflected by beliefs and practices in which all are given the right to speak and all assumed to be able to play a part in realizing their self-liberation. The latter traditions forge horizons and practices which work in, against and beyond representational politics transgressing and combining these forms with others of direct and participatory democracy.

Importantly during the latter days of the mass protests they broadened and deepened as commmunities from the favelas come out to join students and the middle classes to protest police brutality and investment in mega projects for the World Cup and Olympics for the international elite and demand popular power.

Thus the forces that mobilised in the streets and their communities, whilst often visibly populated by students and sectors of the middle classes were also criss-crossed with these popular subjects, their histories, practices and cultures.

The interface between disillusioned youth often mirroring the symbols, demands and practices of student and youth mobilisations around the world and popular democratic subjects with experiences in auto-gestion and radical representative politics is the most potent and powerful possibility for popular emancipatory horizons in Brazil.

Whilst Brazil is no longer in the media spotlight, the crisis of representation facing political elites has not gone away. Protests continue, albeit more quietly, with occupations of muncipal offices and mobilisations against deteriorating public services, continued agri-buisness investment and state corruption. Tomorrow a general strike has been called by union leaderships who are under massive pressure from their rank and file members to respond to popular discontent.

In this conjuncture it is the middle classes, traditional left militants and intellectuals and students who can learn from their urban and rural working class sisters and brothers and in the process create the contours of a reinvented left politics from below. A politics that is multiple, hybrid and in a process of becoming and which transgresses the confines of the now out-dated socio-cultural matrix of the 20th century left and whilst mirrors, is not a mere copy, of autonomous politics in the Global North.

For more on the reinvention of the lefts from below in Latin America see the current edition of Latin American Perspectives, edited by Sara Motta and Laiz Ferguson.

[Öyvind Fahlström was a Swedish artist who spent his childhood in Brazil. His World Map was painted in 1972. He was interested in resistance and excess: politics plus overflowing subjectivity, figurative invention. As he believed, whilst a map is a flat, rule-governed space for a strict social game; it is also an open territory for imaginary play.]

3 Comments

OPINION: Protests bring democracy back to the masses | University of Newcastle Blog | UoN Australia

[…] Magazine, Sara Motta offers the most historically comprehensive analysis of the protests, see here. Situating them in the context of the ascent, and subsequent corruption, of the Brazilian Workers […]

Brazil: Anatomy of a Crisis | Idler on a hammock

[…] via Brazil: Anatomy of a Crisis | Ceasefire Magazine. […]

[…] Read the full article in The Newcastle Herald or in her Ceasefire Column ‘Brazil: Anatomy of a Crisis’ […]