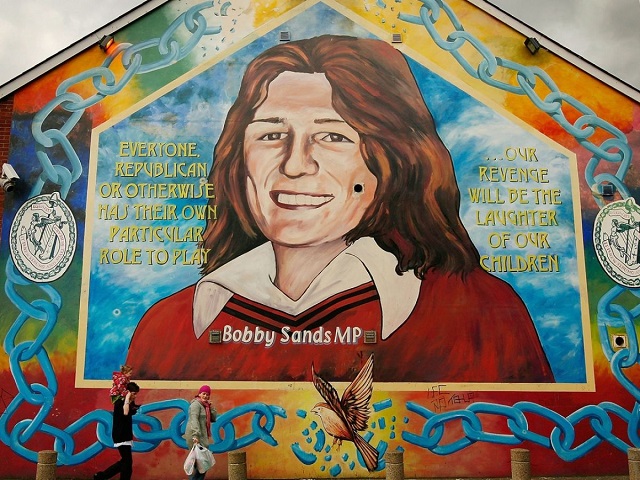

Body, Language, Resistance: the Unfinished Song of Bobby Sands Reflections

Columns, New in Ceasefire, Reflections - Posted on Wednesday, May 5, 2021 15:46 - 0 Comments

On the fortieth anniversary of the death of the MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, Bobby Sands (5 May, 1981) and, at a time when renewed conflict in Northern Ireland, and the impact of Brexit, suggest the possibility of renewed calls for a united Ireland, it seems appropriate to look back at a defining moment in the period prior to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, which now looks under threat. Sands died after 66 days on a Hunger strike protesting the refusal of the British government to treat him and other IRA inmates as political prisoners. Ten other men died on hunger strike later that year.

On the fortieth anniversary of the death of the MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, Bobby Sands (5 May, 1981) and, at a time when renewed conflict in Northern Ireland, and the impact of Brexit, suggest the possibility of renewed calls for a united Ireland, it seems appropriate to look back at a defining moment in the period prior to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, which now looks under threat. Sands died after 66 days on a Hunger strike protesting the refusal of the British government to treat him and other IRA inmates as political prisoners. Ten other men died on hunger strike later that year.

This article will explore the ways in which the body, the Irish language, and writings smuggled out of prison became the principal resources in the building of identity and solidarity in the face of a brutal prison regime in Northern Ireland from 1977-1981, itself part of a colonial order. Irish language classes took place clandestinely at night on a ‘call and response’ basis, as lessons were shouted across the wing of the prison and tapped out on heating pipes. Poems were read out loud, stories told, and songs sung in similar fashion during the intervals when the guards were off duty. It was not just the writings that were a mode of resistance but the physical act of writing itself: the use of holy crosses to etch rune-like on walls, or pencils made out of the bottom of stolen toothpaste tubes, even what might be called the ‘faecal script’ became part of the subversion. Throughout the ‘dirty protest’, walls were covered with excrement but spaces were left for notes from the language classes.

In Archaeology of the Future, Fredric Jameson speaks of a radical form of subjectivity (a new level of being) in which individuality is not effaced but completed by collectivity, and it is this idea which I want to focus upon in considering the role of Bobby Sands’s poems, songs, essays, and diaries in the formation of a culture and politics of resistance. These were all components of a ‘we’ narrative designed to be received both inside and outside the Maze (Long Kesh) prison, an integral part of a politics of liberation based upon a unique oral/aural set of practices as well as a more traditional print tradition.

What Sands was doing was storying community, bringing into narrative what might otherwise be conditions of abjection. Well, of course they were, but he uses them as the basis of a political articulation linked to the wider republican struggle. Written in an agonistic and antagonistic mode, always in relation to the alterity of the authoritarian regime (of the prison and the state) and its narratives of power, objects of the regime (the prisoners) are transformed into a new, potential subjectivity, texts of a group constructing itself. The whole process, not just the writings and the classes, but all the resources of communication within and beyond the prison were proleptic and prefigurative , modelling and rehearsing a future collective solidarity outside. Sands called the incarceration regime the ‘breaker’s yard’ as it sought to break down and destroy the prisoners’ morale, whereas the writings were a means to break with the mental and conceptual schemes of control and the exercise of power.

The writings themselves – produced on toilet paper and cigarette papers, concealed orally or anally and transmitted clandestinely – were all, what have been called, ‘prosthetic texts’ which emphasized the bodily, experiential, sensuous and affective dimensions of ‘testimonial’ writing. The body was at the interface of the event (the prison experience) and its recording and transmission at an experiential site, both temporal and spatial, through which the writer stitches himself into a larger history. It is important to remember that the ‘outside’ is always a referent for the writings which were considered as contributing to the wider struggle.

The Hunger Strike, for example, was much more than about the five demands – 1. The Right not to wear a prison uniform; 2. The Right not to do prison work; 3. The Right of free association with other prisoners; 4. The Right to organize their own educational and recreational facilities; 5. The Right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week – as it was seen as acting as a stimulus, a trigger, for the campaign beyond the prison. Time and space in prison take on a different rhythm and shape from that outside and Sands’s writings enact this difference in the ways in which minute details are concentrated upon, routines are observed almost in slow motion. The Hunger Strike diary, with its dry humour and self-deprecating wit, mixed with images of pain and suffering, was literally written against time (it only records 17 of the 66 days) and death, with its daily charting of weight loss taking on a metonymic function.

Out of what Brecht called ‘Dark Times’, in the face of humiliation, beatings and other forms of inhuman and degrading treatment, writing gave Sands access to the political in the context of a regime designed to depoliticise and criminalise him and his comrades (the commonly used term amongst them). One of his poems is called ‘Comrades in the Dark’. The body, subject to invasive mirror searches, reverses the mirror by becoming evasive (the concealed writing materials all stored anally), and sets up a web of internal and external relationships, or contracts even, generated from the repressive site of enclosure from which the writings become a medium for disclosure, association and communication, the opposite of isolation, compliance and obedience. In other words, the binary structures of the regimes are deconstructed and exceeded. Refusal (to wear prison uniform, to wash, or, ultimately, to eat) was a form of resistance itself (up to 400 men were ‘on the blanket’) but not only in, or for, itself but as part of a larger political strategy.

The scriptural economy (as de Certeau called it) was a mode of action and belonging which contradicted the prescribed emptiness, absence and passivity of the regime; it was counter-insurgent, a form of mastery and subversion, shared in common and manifested publicly. From the privacy of confinement, Sands was able, metaphorically speaking, to change his spatial position through writing, and range and wander in time and space. Having been taken out of time, sentenced, he re-writes the sentence, re-enters time to achieve a number of synchronic meeting points, with the past (memory and the Irish struggles), with his family, with his comrades and with a reading public (via The Republican News). De Certeau describes writing as ‘the concrete activity that consists in constructing, on its own, blank space – the page – a text that has the power over the exteriority from which it has been isolated’. ( Everyday Life, p. 134).

Out of the absence enforced by imprisonment, Sands establishes presence, not just for himself but for his comrades. The writings are a mode of affiliation with a new, horizontal community which rejects the vertical powers of the State, the Church, the prison. They represent – re-present – a change of command, a metaphor for freedom – disclosing and exposing one’s self. Writing becomes a site of action, a way of mastering the present, a form of enlargement and empowerment, agency perhaps, however limited; expansion against the shrinkage of the space and time which is the prison. Arendt called it ‘illumination’:

Even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination, and that such illumination may well come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and in their words, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time span that was given them on earth.

(Hannah Arendt, Men in Dark times, p. 47)

She adds later, ‘the very fact that something is being heard by all confers upon it an illuminating power that confirms its existence’. The writing does not just confirm its existence, or that of Sands himself, but all of his associates in the H-blocks, who the state aimed to depoliticize through the loss of all framework and fellowship. As Allen Feldman puts it in Formations of Violence (1991): “The capacity to symbolize and encode their grim reality was the basis of political resistance”.

The writings are a form of redemptive narrative, restorative of framework and fellowship, replacing the politics displaced by the policy of criminalisation. They are performative in the sense that they bring into being something that did not exist before; or, if it did, it is given a new and radical articulation, which is a ‘we’ narrative, referred to by Sands as ‘the risen people’, a responsive community.

As writing, and writing materials, were forbidden during the blanket protest and the hunger strikes, all of Sands’s work can be seen as transgressive, the product of extreme risk. These conditions of production are vital because they have aesthetic consequences – for example, stylized and often fragmented writings, poems composed according to easily remembered and accommodated formats (rhyming couplets), all determined by the lack of available space on the page, and with the marks and traces of their often oral origins. Repetition is common, paragraph breaks and revision severely limited by the paper used, and there is a necessary rawness and incompleteness at times. There was no scope for revision in a scriptural economy based on shared and scarce resources, the supply of which was unstable and clandestine. Bearing in mind also periods in isolation, frequent wing shifts, body searches and spells of incapacity, then a culture of fractured or ruptured composition emerges.

Questions about the motivation for writing are, in conditions of enclosure, very different from the usual aesthetic considerations. Communication, political communication, is the obvious motive but we also need to think about ways of controlling time on his terms, the challenge, and maybe thrill, of insubordination and the clandestine, and the obligation to others in a similar situation, and as witness to those outside in the struggle. The writing helped to legitimate his claims to be a P-O-W. Resistance occurs when people designed to be passive find the resources to become active and transform the temporal and physical conditions of their passivity (’Nor Meekly Serve my Time’ is the title of an anthology of post-prison writings by survivors). Creativity and ingenuity were hallmarks of this, inventing the dialect of a metaphorical tribe, a cohort of allegiances and belonging.

In this way, Sands became representative in all senses of the word. His writings (sometimes using pseudonyms, circumlocutions, or his name in Irish format) are part of a ‘synecdochal procedure’ which, I would argue, is analogous to a prison escape in so far as ‘once imprisoned, physically removing oneself from domination is a direct challenge to the power of the prison authorities and the state’ (L.Whalen, Contemporary Irish Republican Prison Writing, p.41) which Sands does symbolically as a technique of resistance and the development of a critical consciousness:

The Men of Art have lost their heart

They dream within their dreams.

Their magic sold for price of gold

Amidst a people’s screams

They sketch the moon and capture bloom

With genius, so they say.

But ne’er they sketch the quaking wretch

Who lies in Castlereagh.

(‘Trilogy’, an epic poem written on pages torn out of the Bible)

The simple rhyme scheme, the internal rhymes, and the archaisms partly mock the ‘Men of Art’ but are also wrenched out of their conventional setting (moon and bloom) by the last two lines with their very unromantic subject.

This representational ethos is characteristic of much of Sands’s writing, the sacrificing, perhaps sacrificial, self. There are obvious echoes of Catholic martyr traditions but the majority of the resistance prisoners, including Sands, saw their stance as emphatically secular, even if there are clear borrowings from religious discourse and although many of the men had rosaries and crucifixes, attended Mass regularly, and prayed in their cells. Their Catholicism was cultural, one resource among many in Republicanism. Clear evidence exists of the influence felt by the men of the liberation struggles in Cuba, Vietnam, South Africa, Algeria and Nicaragua. Sands gave lectures on the Sandinistas, and quoted from the works of Mao, Guevara and Fanon.

Sands is attempting in ‘Trilogy’ to develop a more socialized model of composition and textuality, something he also does in an extract from his Hunger Strike diary, which consists of a series of sentences constructed around an ‘I’ (an authoring subject): ‘That’s another day nearer to victory, I thought, feeling very hungry….Nothing really mattered except remaining unbroken’. The ‘I’ sentences then yield to a collective ‘our’: ‘They cannot or never will break our spirit. I rolled over again freezing and the snow came in the window on top of my blanket. Trochfaidh ar la, I said to myself, Trochfaidh ar la (our day will come).

Leave a Reply