The Anti-Imperialist A Struggle for Black Community

New in Ceasefire, Politics, The Anti-Imperialist - Posted on Sunday, March 27, 2011 0:00 - 1 Comment

Adam Elliott-Cooper

The dominance of imperialism and other forms of oppression are intrinsically linked with the past. However, the history of resistance allows us to learn how best to overcome it. One of the most useful places in history to learn these lessons, are the lesser-known organisers and methods employed in the US civil rights movement.

As Black activists, many of us cling to the achievements of the past when resisting capitalism, racism, imperialism, patriarchy or other illegitimate power structures. We can often feel disempowered and frustrated in our current historical context where hyper-consumerism and tokenistic progress has engendered individualism and political apathy among many oppressed groups.

One of the most compelling examples of resistance to oppression is that of the civil rights movement in the United States. The movement revolutionised the political landscape in the United States forever. Well documented are the non-violent protests, boycotts, occupations and legal action encouraging African Americans to register for the vote. The institution of racial segregation included all areas of public life such restaurants, public transport, schools and professional sports.

Until 1954, the idea that whites and African Americans were ‘separate but equal’ was finally abolished, as the courts and legislators were forced to accept that racial segregation was based on an uneven and discriminatory power relationship. Also well documented, are the ‘big leaders’ like Dr. Martin Luther King, as well as the individual actions of people Rosa Parks – these are often assumed to be the key features of the struggle for Civil Rights.

Applying this version of history to our current struggles however, can often be problematic. In order to emulate the consciousness and actions of the past, it is important to understand how consciousness was raised, and organised into action. Although recognition of the ‘big leaders’ is important, the lesser known grassroots organisers, and the methods they employed was an intrinsic part of the civil rights movement. It is therefore vital that we understand how, particularly young people, became actively engaged in popular struggle.

A multitude of different organisers worked tirelessly to involve young people in the socio-political issues of 1950s US society. One of the most influential was Ella Baker. Baker started her work in the late 1920s in New York, organising a space for African Americans to discuss their relationship with America’s and Africa’s past, called the Negro History Club.

She was also heavily involved in independent journalism, editing the Negro National News. She helped poor African Americans set up food co-operatives during the Great Depression and contributed to the setting up of an adult education centre for Latinos and Blacks in deprived areas of New York. She was soon head-hunted by the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People), and assigned a role organising communities in the South, where racism was far more overt, and often resulted in torture and lynching. She would often joke that the first NAACP chapter in the South she worked with was just her and a phone box, but her capacity to organise and educate soon saw her influence flourish.

One of Baker’s core concerns, were the class divisions between African Americans, with one contemporary activist observing: “Ms Baker was sensitive to the way class antagonisms, real or imagined, could undermine everything. An important part of the organiser’s job was to get the matron in the fur coat to identify with the winehead and the prostitute”. In other words, Baker saw all participants in the movement as leaders, and based on that principle, she set out to investigate the needs of the local community, and began organising around them.

Bakers programmes soon became well –established. They centred on organisational development (such as holding onto members), mounting public campaigns, dealing with police brutality and employment discrimination. Baker brought in organisers from surrounding towns who had successfully tackled these issues. This served two purposes. It helped local organisers to tackle the problems they were facing more effectively, and helped everyone to see that the issues they were facing locally, was part of a larger pattern of discrimination.

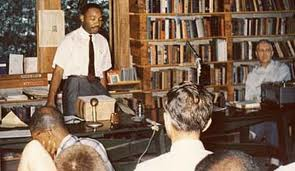

By the mid 1950s, Ella Baker dedicated her work to building strong local organisations, made up of small groups of people maintaining effective working relationships among themselves but also maintaining contact in some form with other such cells, so that coordinated action would be possible. Baker also helped to create a central space for many of these cells to learn and organise together – the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, which trained famous activists like Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr as well as influential organisations like the SNCC (Student Non-Violent Co-ordinating Committee).

The Highlander Folk School was a space for young activists to meet up and access key resources including tactical knowledge, training techniques and a well contextualised understanding of racism and imperialism. Many youth activist groups emerged from the school, most notably the SNCC.

Baker helped bring together young activists taking the lead in the struggle for civil rights, as well as those who were in the embryonic stages of building up resistance to segregation. Baker has always maintained that she was little more than a facilitator, insisting that the oppressed themselves, collectively, already had much of the knowledge needed to produce change.

The political outlook and organising methods of the SNCC drew heavily from Baker’s influence. All decisions were made consensually. Stockley Carmichael, a long-serving participant in the Highlander School, would often complain about the long meetings which went on into the night. Baker would often calm him down, by saying that everyone needed to genuinely understand and agree with the issues, if we are to engage in a struggle of the people.

Upon reflection, Carmichael observed that when you had strong activists from all over the country in a meeting, voting in a decision on a majority was not a viable option. The young participants at the Highlander School were strong-willed, and if they did not believe in a decision, and understand why other people in the group had made it, they would not be fully dedicated to the actions which would follow. Organising and education were intrinsically linked from start to finish.

Upon reflection, Carmichael observed that when you had strong activists from all over the country in a meeting, voting in a decision on a majority was not a viable option. The young participants at the Highlander School were strong-willed, and if they did not believe in a decision, and understand why other people in the group had made it, they would not be fully dedicated to the actions which would follow. Organising and education were intrinsically linked from start to finish.

The members of SNCC used the skills and understanding they gained from Ella Baker and the Highlander School to become a collective of ‘mobile organisers’. They went into communities to help set up similar spaces to those created by Baker, facilitating the organisation of local people to represent themselves and their community. Stockley Carmichael observed that this philosophy lent direction and continuity to what was a formless and spontaneous student uprising.

Rather than informing young people of the issues surrounding white supremacy, Baker, and later the SNCC, would run workshops which began with asking the participants what they wanted to learn. The workshops would end with what they planned to do when they got home. One of Baker’s earlier workshops included Rosa Parks, who was struggling in Montgomery, attempting to engage the young people in that area in the fight for civil rights.

The actions which followed on from these organising spaces and meetings are again, well known. The marches in Washington, the occupation of segregated restaurants, the boycotts of segregated buses and the ‘read-ins’ in segregated libraries are but a few of many forms of peaceful direct action taken up by different groups of activists in the 1950s and 60s.

Actions often led to students suffering physical abuse from the police – a dedication which convinced many civil rights organisations to heavily recruit young people. Action by young people was also international in scope; for example, the NAACP youth wing pushed for anti-Vietnam war motions to be passed, the SNCC was one of the first organisations in America to make a public stand in solidarity with Palestine, in addition to promoting a Black Power and Pan-African oriented agenda.

It is difficult to be certain what the best course of action is for resisting imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy today. However, the inspiring actions of the civil rights movement provide some useful models for today’s actions. Equally as important, but less tangible, is what we can learn from the rise in political consciousness of many Americans, particularly African Americans about all forms of power relations, in addition to the power of racism in the US at the time.

The great leaders were an intrinsic part of the civil rights movement, but they relied on the will and understanding of a generation of newly politicised Black communities. These lessons have not been forgotten, with social movements across Latin America as well as parts of Africa and Europe employing similar methods of organising. There is no perfect formula for building a united resistance for liberation, but the clues of the past could well steer us in the direction we’re looking for.

Adam Elliott-Cooper, a writer and activist, is co-editor of Ceasefire. His article on race politics appears every other Sunday. He tweets at @adamec87.

I think it is imparative that we also study the account of Fannie Lou Hammer from Montgomery County Missisippis who studied under Thurgood Marshall in the Regional Council for Negro Leadership, organized the Missisippi Freedom Summer for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Comittee. She was the Vice-Chair of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and was so vocal in her adovocation of civil rights through voting rights with the singing of her hymns that she was sterilized in 1961 and so impairingly threatend Lyndon Johnson’s re-eleciion that he sent J Edgar Hoover to try to shut her up. She created the phrase, “I’m so sick and tired of being sick and tired.”