David Lammy and (Mis)understanding Violent Coercion The Anti Imperialist

New in Ceasefire, The Anti-Imperialist - Posted on Sunday, January 29, 2012 22:25 - 1 Comment

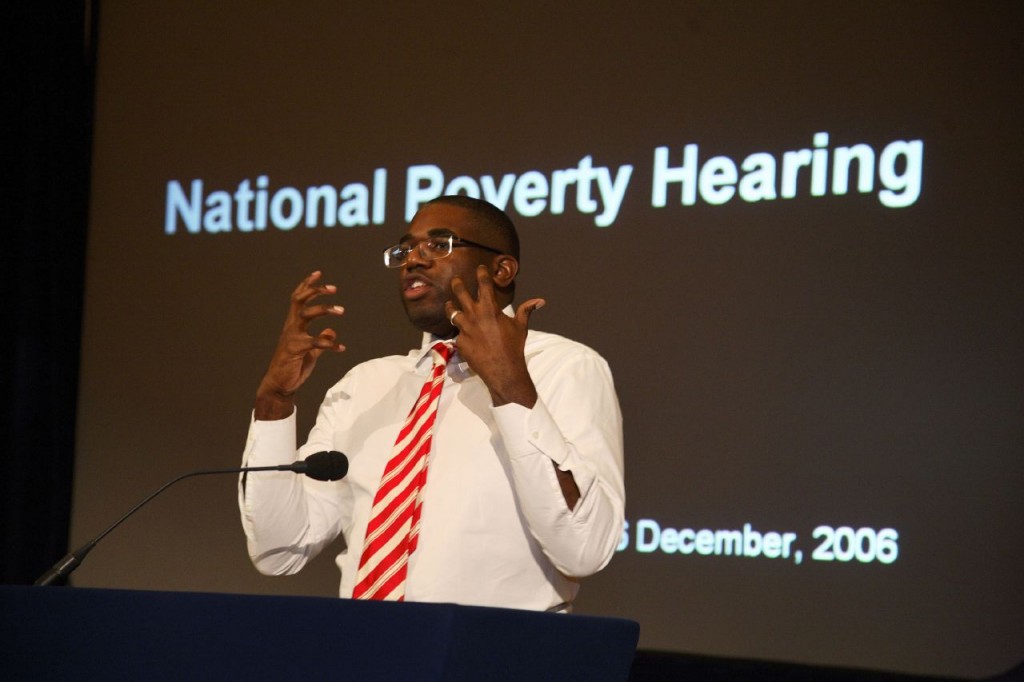

David Lammy MP has had to undertake some quite serious back-tracking over the past 48 hours. After his comments in support of corporal punishment, headlines in the mainstream press included “Smacking ban led to riots because parents fear children will be taken away if they discipline them”. As the elected representative of Tottenham, and the appointed representative of much of the African/Caribbean population of the UK (or so it seems), Lammy thought he’d found common ground among the Black parents of Tottenham, and the conservative establishment his policies (and rhetoric) often reflect. However, this hasty assumption meant he failed to factor in the class, gender and post-colonial context in which his statement was made, in addition to the obvious racialised links made between the August ‘riots’ and urban crime at large.

One of the most striking aspects of Lammy’s remarks, is his inference that the British state is doing too much to protect young Black people from violence. According to Lammy, Black communities “live in fear of the social services turning up on their doorstep”. It is indeed true that social services operate far more in working class (and by extension Black) communities, due as much to institutional racism as demand – we see that the stress and trauma of socio-economic deprivation tends to go hand in hand with a prevalence of domestic abuse in these areas. However, even if we are to assume that Lammy is right, he makes little effort to bring attention to the other agents of the state, a knock on the door Tottenham constituents and Black communities live in far greater fear of.

In 2008, Frank Odame died from head injuries after the UK border agency raided his flat in Redbridge. In that same year, a Ghanian man fell from the third floor of a block of flats and another broke both his legs following a raid on a restaurant in which he was working. Both these people too, were being pursued by the UK border agencies. Asylum seekers driven to near and actual suicide, in preference to the prospect of UK Border Agency’s detention centres, speaks volumes of their extensively documented ill-treatment. And although Lammy has focused his attention on some officers involved in unlawful killings, such as that of Mark Duggan, he has never attempted to address the legislative and institutional flaws which often lead to deaths in the hands of police. In the same way that Lammy understands that the isolation of specific social workers will not stop Black/working class communities feeling vulnerable to the state when raising their children, he must surely understand that the targeting of specific officers will not stop institutional discrimination in other mechanisms of the state.

Secondly, (and perhaps more controversially), Lammy’s approach to corporal punishment, I feel, is profoundly damaging to Black, working class,or any community which wishes to view children as human beings, rather than property. To illustrate this, an anecdote from bell hooks is useful:

“Often I tell the story of being at a fancy dinner party where a woman is describing the way she disciplines her young son by pinching him hard, clamping down on his little flesh for as long as it takes to control him. And how everyone applauded her willingness to be a disciplinarian. I shared the awareness that her behaviour was abusive, that she was potentially planting seeds for this male child to grow up and be abusive to women. Significantly, I told the audience of listeners that if we had heard a man telling us how he just clamps down on a woman’s flesh, pinching it hard to control her behaviour it would have been immediately acknowledged as abusive”

Hooks not only highlights the populist appeal of corporal punishment, to which Lammy panders, but also the psychological effects of growing up around violence. Learning that power and control are exerted physically is the exact mindset which led to the ‘riots’ which Lammy is so hasty to condemn. In fact, corporal punishment has a very lousy track record when it comes to discipline. There is ample evidence to suggest not only that corporal punishment is not an effective way of teaching children the difference between right and wrong, but it in fact leads to an increased likelihood of the child being critical of the moral values his/her physical punishment was supposed to instil. Policy shifts in West African private schools allowed academics to follow the progress of similar children, some of whom were disciplined with corporal punishment, others who were not. The study found that children in the punitive school performed significantly worse than their counterparts in the non-punitive school. Similar studies have been carried out in Europe and North America, with similar results.

What David Lammy is in fact doing, is not protecting Black and working class parents from social workers and other intrusive state agents. He furthers a culture of domination in which we are socialised into accepting violence as a legitimate means of control, even when this violence is disproportionate to the threat, or perceived threat. As has been widely documented, the race and class of populations often plays a critical role in their chances of experiencing violence at state hands. The logic of the exertion of violent control led David Lammy to vote for a stronger asylum system, Labour’s anti-terror laws and the Iraq war, and informs his latest public support for the physical control of children, particularly those in Black and working class communities. Only by challenging both domestic and state violence, can we properly understand the social, economic and political issues which lead to young people growing up in poverty, rioting and dying at the hands of police.

1 Comment

Maria

This is a brilliant, timely and informative article which addresses the assumptions underpining Lammy’s position whilst bringing much needed attention to wider issues of state violence experienced, disproportionately, by the black community. Hope Lammy reads it.