Multiculturalism Misunderstood The story of Mervin Mitchell

New in Ceasefire - Posted on Sunday, March 20, 2011 12:08 - 0 Comments

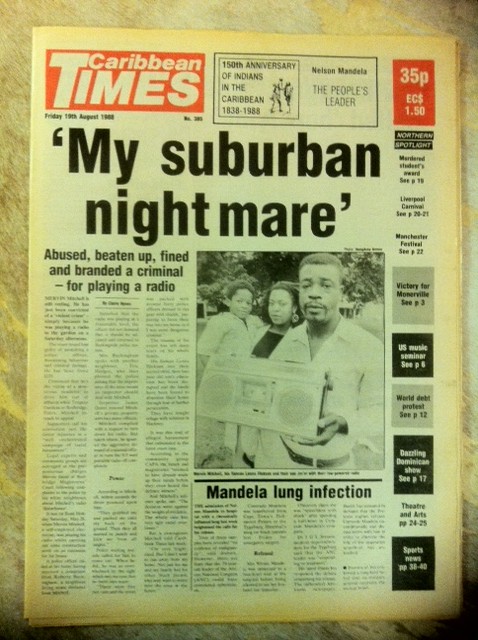

While sifting through one of the new collections at London’s Black Cultural Archives, the story of Mervin Mitchell was uncovered in Issue No. 335 of the now-defunct Caribbean Times. The Black British man had moved his young family to the predominantly-white London Borough of Redbridge for a new life in the suburbs only to return to the safe familiarity of Hackney. In light of Prime Minister, David Cameron’s recent assertion that “multiculturalism has failed”, Symeon Brown considers what Mervin’s story can add to the debate.

It was May 28, 1988. Mervin Mitchell was enjoying the Bank Holiday with his pregnant fiancée, Leona Hickson, and their four-year-old son, Jor’el, in the home they’d just bought in an affluent Redbridge suburb. In addition to the spacious garden and summer weather, Mervin had much to be happy about: his pending nuptials and a new addition to the family who was months from being born.

While listening to music on the radio, the family were interrupted by a policeman who explained he was responding to a complaint of loud music from neighbour Roberta Buckingham. Mervin was instantly apologetic and turned down the volume to a level the policeman approved of. Content, the officer returned to Barkingside Police Station and the family settled back into their relaxed afternoon.

The article claims Ms Buckingham was still unhappy and called on another neighbour, Eric Hedges, who made a second complaint, but this time insisting that an inspector handle the matter.

Following the call, Inspector James Quinn with two officers in tow visited Torquay Gardens later that afternoon. Mervin was ordered to turn off his radio completely. He replied he was happy to turn the music down but maintained his right to listen to music in his own home. His comments were allegedly met with a savage beating. In an emotional account, he recalled how “they grabbed me and pushed me on the ground. Then they all started to punch and kick me from all angles” before being marched out of his house to see “five riot vans and forty police officers in riot gear with shields preparing to force their way in.”

Amid the hysteria, Mervin’s fiancée miscarried their child.

Mervin was convicted and fined £225 for demonstrating ‘threatening behaviour’ and not obeying the policeman’s orders. Community group CAPA stated at the time that the magistrates “seemed to have already made up their minds before they even heard the defence witness”.

Last month, British Prime Minister David Cameron accused ethnic minorities of failing to integrate themselves into British society and effectively excluding themselves from a national British identity. Mervin Mitchell’s story is a reminder of race relations and identity formation in Britain.

Mitchell’s narrative can be considered one of attempted integration met with rejection and marginalisation by both the state and the white local majority. He had attempted to integrate and make himself at home in the white majority community of Redbridge rather than an inner city area such as Brixton, Hackney and Tottenham that had large African, Caribbean and Asian communities.

In an ironic twist, Redbridge is no longer the desired suburb it once was and is synonymous with other former metropolitan suburbs such as Edmonton, Wood Green and Leyton that have been consumed by relative deprivation and home to migrant communities following the exodus of socially mobile white communities who have used the market to refuse integration. This phenomenon of the ‘white flight’ is not unique to Britain and can be paralleled to many of America’s once-thriving cities such as Detroit and Baltimore, the latter well-documented by award-winning drama series The Wire. This history suggests that the formation of majority African, Caribbean and Asian communities is largely a result of the self-removal of socially mobile white communities from multicultural spaces.

But Mervin’s story is not only one of social alienation but also institutional injustice and racism. Mervin’s immediate decision after what was described by the Caribbean Times as a ‘suburban nightmare’ was to abandon his new house and take refuge with relatives in Hackney that had and continues to hold a large black population. Although Britain’s inner city communities are not immune from institutional discrimination – evident from the Notting Hill, Brixton, Southall and Broadwater uprisings – the psychology of collective safety, and community shared among non-white communities who collectively experience inequality is significant. It helps explain why African, Caribbean and Asian identities are absent from particular social spaces. This collective memory of fear and exclusion should be considered when understanding how the identity of British minority communities are formed.

Cameron’s speech attempted to define an objective monolithic British identity that did not include many of the communities who call Britain home and self-define as British. If multiculturalism in its basic definition refers to a society, nation or state that is made up of different communities with their own social norms, lingual traditions and historical formation, then David Cameron has completely disregarded Britain’s organic multiculturalism as a feature of its history. He is engineering Britishness into an exclusive discourse that undermines the British history that includes Mervin and thousands of others like him.

Without doubt, Britain’s multicultural heritage dates back much further than 1988. However, the history of race relations in Britain, as in the Mervin case, is not just one of self-removal from a minoritised community, but through rejection from a white majority. Traditional English communities are guilty of the same thing – preferring moving on to mixing in. If we forget stories like Mervin Mitchell’s, multiculturalism will remain misunderstood.

Symeon Brown, a writer and activist, is an archivist at the Black Cultural Arcives in South London.

Leave a Reply