Patriarchy, Islamophobia and Misogyny: On challenging the politics of Sikh Youth UK Comment

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Tuesday, October 17, 2017 17:23 - 0 Comments

By Katy P. Sian

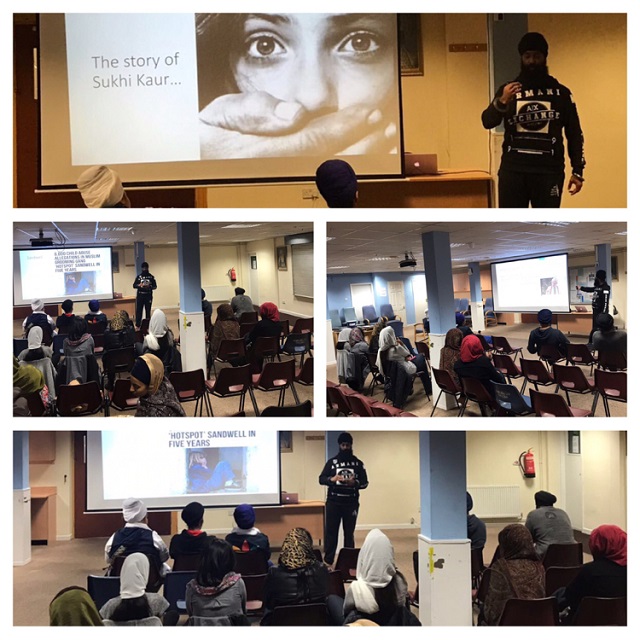

(Still from a 2013 BBC documentary on grooming victims within the Sikh community)

Yesterday, the Independent published an article — to which I contributed — on Sikh Youth UK and their fear-mongering activism against so-called Muslim ‘groomers’. Sikh Youth UK describes itself as a movement that aims to empower and support the Sikh community. It presents itself as a community hub for events, activities and support networks, offering ‘guidance’ and raising awareness around alcohol, drugs and bullying. In 2016, it produced a film entitled Misused Trust, which presents a fictional account of a vulnerable victim of ‘grooming.’

Unsurprisingly, in the 24 hours since its publication, the Independent piece has engendered a deluge of trolling and abuse, much of it directly against my own criticisms of Sikh Youth UK’s problematic record of Islamophobia and misogyny. Although the Independent article included comments by a male representative from ‘Sikhs against the EDL’ supporting my analysis, there was, tellingly enough, very little mention of this by the trolls, who appeared to focus their attacks on me. The sexist nature of the harassment echoed the misogyny seemingly prevalent among supporters of Sikh Youth UK.

Needless to say, the trolling was conducted almost exclusively by male voices. This is constitutive of a familiar gendered power dynamic in play, one that manifests itself most clearly whenever a female voice is seen to be challenging a dominant, generally male, narrative. A cursory glance at the set-up of Sikh Youth UK shows an overwhelming presence of middle-aged Sikh men. In its sensationalist, Islamophobic campaign around ‘grooming,’ the organisation has been on tour up and down the country, hosting a series of ‘awareness-raising’ talks around the “Dangers in Modern Society.”

From available photographic evidence of these events, this group seems to be led largely by Sikh males who are apparently obsessed with stories of ‘grooming.’ It is rather perplexing that these men believe they are best placed to ‘educate’ Sikh women about the ‘perils’ of contemporary Britain. Underneath the mask of ‘safeguarding’, however, is a sinister stench of male chauvinism based on vigilante attempts to regulate Sikh female bodies. The trolling directed at me, therefore, is yet another attempt within the broader effort to discipline Sikh female voices.

One of Sikh Youth UK’s events (Source: Twitter)

The production of this narrative appears to display a disturbing form of pornographic aesthetics, aimed at satisfying a voyeuristic gaze. In much of the material produced by this organization to ‘expose grooming,’ there is an alarming predominance of a handful of Sikh males seen interviewing female victims about their personal experiences. There is something rather insidious at work here, whereby Sikh men appear to be at the forefront of these discussions. To deny these women a discursive voice is not only to pander to early anthropological studies on ‘passive’ South Asian women, but also locates them as bodies that require policing by Sikh males.

Moreover, this tasteless and insensitive fascination with sexual activity seems intended to take away the agency of Sikh women, by locating them as subjects who can only be rescued and saved by Sikh men. The continual emphasis on the vulnerability of Sikh women appears to form the central element upon which fears and anxieties about the Muslim ‘other’ are projected. As such, the Islamophobic figure of the Muslim ‘predator’ works as an important symbol used to control Sikh females through cautionary tales and paranoid fantasies.

According to this vision, any form of agency enacted by Sikh women undermines ideas of Sikh masculinity, and the preoccupation with Muslim ‘groomers’ acts as a vehicle for cementing hegemonic patriarchal norms within the community. This hyper-masculine performance is a clear exercise for establishing dominance over Sikh women.

According to this vision, any form of agency enacted by Sikh women undermines ideas of Sikh masculinity, and the preoccupation with Muslim ‘groomers’ acts as a vehicle for cementing hegemonic patriarchal norms within the community. This hyper-masculine performance is a clear exercise for establishing dominance over Sikh women.

In light of the Weinstein scandal, it is more important than ever to challenge systemic forms of patriarchy, abuse and power. Interestingly, Sikh Youth UK, who laud themselves as anti-grooming champions, have seemingly little to say on Weinstein. Moreover, they have not only played down instances of child sex abuse perpetrated by non-Muslim offenders but also failed to adequately address sexual abuse within the Sikh community itself — a clear sign for many of how deeply-embedded Islamophobia and patriarchy are within the organization.

By calling out Sikh Youth UK on their problematic politics it is perhaps not all too surprising that the backlash against yesterday’s article in the Independent has come my way. Charges that I am a ‘Sikh loather’ or a ‘terrorist sympathiser’ are key elements of a narrative that works to close down spaces for presenting alternative, critical understandings. As such, opportunities that may pave the way for an enabling dialogue are prevented.

Whenever presented with such hostility, I am always reminded of an interview I carried out some years ago with Professor Ronit Lentin. Lentin is a leading academic who happens to be Jewish and critical of the Israeli occupation of Palestine and its associated politics of Islamophobia and patriarchy. As a result of her fearless outspokenness she has received an unprecedented amount of abuse. When discussing the emotional labour attached to this kind of work, I always remember her saying: “there are many people who try to fight me, but it’s not important; it’s a price to pay, but it’s a very small price.”

Leave a Reply