‘Get Out’: A bone-chilling, discomfort-inducing, laughter-provoking artistic and political triumph Film

Arts & Culture, Film & TV, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, April 7, 2017 21:22 - 1 Comment

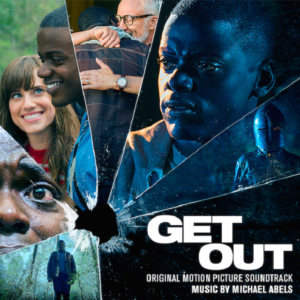

Chris Washington (DANIEL KALUUYA) is the guest of a very odd garden party in Universal Pictures’ “Get Out.”

Warning: This review contains plot spoilers

“I’d have voted for Obama for a third time”, the central father figure of Get Out assures us within minutes of coming on screen. Though the spectres of police violence and white victimhood are never far, it is the thinner end of America’s racist wedge that Get Out tackles head-on.

What’s revealed throughout is that seemingly superficial levels of racism, those of compliments (“with your genetics and build you could be a real beast in the ring”) or coy insinuation (“is it true?” [that black men are good in bed]), are reliant on an objectifying dehumanisation operating at a deeper, more unconscious level. This is aptly brought to the fore when the father deters the main character, and the film’s hero, Chris (played by Britain’s own Daniel Kaluuya) from entering the basement, by telling him, “there’s just black mould down there”. There always is.

White suburbia’s liberal racism relies on the surreptitious perpetuation of depraved, racist tropes. The basement, once more, is used in the storytelling to represent the subconscious. Racism is acted-out openly, yet at the same time goes unrecognised, pushed below consciousness. In Get Out this recognisable composition of liberal racism exists through the direct colonisation of black bodies: Transracialism. Appropriation, taken to its absolute height, is the wholesale taking-on of a proposed ‘blackness’ by white people. In Get Out, this is writ large, the literal taking over of black bodies by whites, who desire to live ‘through’ these black bodies for their perceived ‘talents’ and ‘strength’.

This accounts for a lot of what we see within our own society: for example, how traditionally black hairstyles on white people do not only receive the same policing, but can work as a form of cultural capital. This works in most cases as an undoubtedly racist contortion. Justin Bieber is a case in point: It is no coincidence Bieber matched his dreadlocks with gang bandanas on his recent Purpose music tour. The teenie-bopper image was to be finally cast aside with a scaffolding of black masculinity. A performance deemed safe enough on Biebs so as not to deter ticket sales.

This accounts for a lot of what we see within our own society: for example, how traditionally black hairstyles on white people do not only receive the same policing, but can work as a form of cultural capital. This works in most cases as an undoubtedly racist contortion. Justin Bieber is a case in point: It is no coincidence Bieber matched his dreadlocks with gang bandanas on his recent Purpose music tour. The teenie-bopper image was to be finally cast aside with a scaffolding of black masculinity. A performance deemed safe enough on Biebs so as not to deter ticket sales.

Another dimension of “whiteness as power” is its incredible ability to commodify, turning otherwise-censored ‘blackness’ directly into capital. This adorning of whiteness with gestures of ‘blackness’, through cultural re-appropriation, reaches its apex in the taking on of black identity itself: ‘Transracialism’. Rachel Dolezal has brought this term into mainstream discourse, most recently through her appearance on the BBC’s Newsnight programme, though the integrity of the category remains a matter of contention. In Get Out, the white characters literally bid at an auction to determine who gets to steal and occupy the black body on offer. Lured into their rich, secluded, suburban trap, Chris is next on the list.

The fact that fetishism enables the colonisation of black bodies is made crystal clear throughout the film. Chris’s friend from back in Brooklyn, Rod, tells police officers, to their incredulous amusement, that he believes black people who’ve gone missing are being made into “sex slaves”. However, Transracialism goes one step further: whites taking themselves as a black sexual object: Feared, lusted after, defended against, almost every libidinal quality possible. This necessarily involves a degree of narcissism, which the – inevitably – white person (because blackness cannot intrude on white society) is entitled to enjoy in every way possible — even, when they fancy it, through adopting blackness.

As such, Blackness is a territory to be plundered, whilst whiteness exists as a category that is totally impervious and unassailable. Fetishism requires dehumanisation to exist, with the humanness of a person, the recognition of the subject, transferred instead into an object, making it human instead.

What Get Out demonstrates is that being black, like being white, is a structural position and that entails a permanency. That each is a state of ‘being’ beyond any combination of identification, skin shade or cultural production. There is a sociality constituted by power that designates black or white subjectivity, a lived reality, far beyond identity selection.

This is what makes white colonisation of black bodies necessarily a subjugation of those black bodies. Get Out’s white characters (Grandma and Grandpa), who have stolen and are now occupying black bodies, still live white lives, free from racism. Socially-constructed positions cannot be chosen via mental identification. Like how Dolezal, though now a social pariah, still lived a racially privileged (however violent) childhood and continues to enjoy living free from racist presumptions (despite her denials)

Experience is not simply a person’s recollections of experience, but what they were subject to. The Transracial figures of Get Out enjoy the same autonomy and lack of racist expectation to be able to negotiate their roles – as gardener and maid – which are soon revealed as play-acting for the benefit of the Chris character. The only authentically – i.e. actually – black person in the household, violently endures all of the repercussions that identity entails.

There is another central aspect of the film that all audiences can probably recognise: the outwardly wholesome norms of White American life are actually built on a past that is sinister and rotten. Furthermore, the racism of white people is as much to do with aggressive envy, fragility and insecurity as with anything else. More importantly, the fact that black bodies are superfluous to the specific psychological processes of white racism, is also why they are its ready target.

There is another central aspect of the film that all audiences can probably recognise: the outwardly wholesome norms of White American life are actually built on a past that is sinister and rotten. Furthermore, the racism of white people is as much to do with aggressive envy, fragility and insecurity as with anything else. More importantly, the fact that black bodies are superfluous to the specific psychological processes of white racism, is also why they are its ready target.

Get Out’s ending brings the audience to initially see a police car and think, “it’s the cops, he’s fucked!” Cue audible gasps. Chris, our hero, is to be cast as a ‘typical’ black criminal and likely shot down on sight. It’s so brilliantly done that we initially fail to notice that the film has won literally its entire audience over to its political position. For achieving that alone, it has to be up there with the best film endings of all time.

Get Out manages a seamless concoction of bone-chilling, discomfort-inducing and laughter-provoking moments, whilst at all times being relentlessly political in a way that takes you with it rather than through bashing your head into its metaphorical placard. The fact that this has made it all the way into mainstream cinematic fodder is surely due, in large measure, to the remarkable impact of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Racism, like sexism, is predicated on the power – and located within the mind – of the beholder of these oppressions and privileges. It does not matter whether black people identify as white, in the same way in which it does not matter whether women call themselves by any other name. They remain subject to the same conditions. What Transracialism tries to do, thus, is attempt to obfuscate that social reality through contrived manipulations of rhetoric and language: Who is really oppressed today? Isn’t it cool to be black now though? Doesn’t social construction mean something doesn’t exist finitely? Surely subjective fluidity means we can change subject position at will?

In this context, Get Out reveals the impermeable structural nature of oppression, the rotten white core of liberal racism and the fetishistic heart of Transracialism.

1 Comment

rene

great , but putting things into perspective binary oppositions as read in your article its not something having to do with racism morever its capital in its latter form that which has exterminated all oppositions bringing about something unheard of 50 or 60 years ago : chaos , but a normalised chaos i mean it doesnt matter if youre black or white ,we have internalized the prejudices, rules, stereotypes the same way we have become normalised in every possible way regarding every conceivable oposition or better thers no oposition anymore when the terms are able to switching positions as ( i dont know whos in charge here, certainly are not power relations ala foucault) you wish , i recently saw chapelles stand up the age of spin and he tells about having met OJ 4 times and in one of these encounters OJ is asked by some reporter to take a stand on racism , he replies hes there not as a black fellow but as a OJ Simpson so ideology operates at all times it seems all embracing it is everywhere and yes even in the unconcious level specially there (zizek)