‘Who said this would be investigated?’ Bangladesh and the May 2013 Massacre Special Report

New in Ceasefire, Special Reports - Posted on Monday, May 5, 2014 17:53 - 12 Comments

By The Brethren of Black Lotus

- Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) is a powerful, creative response to the the bombing of a Spanish town by German aircraft supporting the ultranationalist forces of General Franco

One year on, we begin to deconstruct the comparative silence surrounding the government brutality unleashed against supporters of Hefazat e Islam’s 5th May protest programme by the Bangladesh state. Since then, on January 5th, the establishment responsible for the massacre has secured reelection with the support of its international development partners and strategic allies, making the voices of the brutalised and bereaved no easier to hear.

Such a complex state crime will take significant time, effort and social transformation to understand and reconcile. As a point of public reference, we present an interview of a survivor and organiser of the protest. It is important to do so at this stage because although the 6th May Massacre remains in local public memory and has been referred to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for investigation, domestic and international agencies continue to manipulate human rights, development and war on terror narratives to cover their complicity and preserve their power, audience and access to resources.

What do we know about what happened?

Last year, on the 6th May 2013 at half two in the morning a ‘clearance’ operation was mounted against unarmed protesters camped around the Water Lily roundabout (Shapla Chottor), a memorial for those who died in the 1971 Bangladesh War, in the commercial hub of Motijheel, Dhaka. Power into the area had been cut earlier, leaving tens of thousands of men young and old in darkness, unaware of the huge build up of security forces around them.

The day before, the protesters had marched from six points around the city, an estimated million strong, wearing national flags and asserting their rights to protest against religious defamation, discrimination and violence against their community amongst other matters. Many had been attacked by ruling party cadres and government forces, with firearms and more intimate bladed and blunt weapons, mounted on riot cars and motorcycles. Protesters seeking refuge in the national mosque were attacked by gunmen on motorcycles. The savagery on show was witnessed by the nature of the injuries inflicted, survivor testimonials and social media video footage. Several of the deceased had been brought to Shapla Chottor on stretchers, while the walking wounded and dying filled the hospitals that would accept them. According to a deaf-mute grave digger interviewed by Al Jazeera (before they lost interest) several bodies found themselves buried in a pauper’s graveyard.

Later in the night, a passerby shared a heart-trembling eye-witness account of his patheticness in the face of police lines shooting at traditionally garbed protesters then pulling them out of the smoke and handing them to Awami League ruling party cadres to beat. In a classic inversion of reality, these same students and teachers of religious disciplines, would be accused by their tormentors of burning the very Qur’ans they devoted their lives to study.

The marchers could never have known the unprecedented violence with which their state would act against them during the day, the night and as they tried to make the return journey home. One of the growing number of educated young professionals politicised by this episode of Bangladesh recounted to me how a group of young men from his ancestral home defied their local ruling party thug’s threats and went to the Dhaka protest, three of them were killed there and three more upon their return when the local police assisted the ruling party men. The real Bangladesh today is an environment of distrust, intimidation and fear of recrimination, it is unsurprising that we cannot hear the voices of the terrorised, unless we chose to actively listen.

During this epic mobilisation and deployment of tens of thousands of police, border guards and the notorious British-trained Rapid Action Battalion, the kitchen sink was thrown – Kobra riot cars, hot water, sound grenades, live ammunition, shotguns and rubber bullets – against crowds of tens of thousands of men, leaving – at a minimum – scores of them dead and many more injured, traumatised and running for their lives. Just like their counterparts during the Gujarat massacres of 2002, the police would play games with their victims, pretending to help them but guiding them into ambush.

The only silver lining is that humans can still tend to nobility, even in the worst of times. Some police could be seen to try and have a restraining influence on their colleagues. When accountability comes for Commissioner Benazir Ahmed of the Dhaka Metropolitan Police (ironically a former UN peacekeeper in Bosnia) and company, these differences and the actions of kind strangers will matter.

Dhaka Met Police (DMP) Commissioner Benazir Ahmed shakes hands with US Ambassador Dan Mozena. Curiously, just days after the massacre, the US State Department completed a 9 day training programme with the DMP on “Tactical Management of Special Events”.

Dhaka Met Police (DMP) Commissioner Benazir Ahmed shakes hands with US Ambassador Dan Mozena. Curiously, just days after the massacre, the US State Department completed a 9 day training programme with the DMP on “Tactical Management of Special Events”.

Several social media videos and sorrowful images emerged immediately after the massacre, as people in Dhaka desperately uploaded the contents of their phones and cameras and struggled to relay eye witness accounts of events. This extraordinary content came unfiltered and unassisted if not dismissed by what may go down in history as Bangladesh journalism’s and civil society’s worst hour.

One year on, the lights on Shapla Chottor remain switched off. There has been no independent and competent inquiry into what happened. Investigations have been obstructed by the state, while survivors and their sympathisers bullied into silence. in parallel, Hefazat e Islam, the umbrella group whose protest was attacked, have been under siege themselves, and struggled to be heard in their own words. Before hearing one of their voices in detail, the performance of the media and human rights sector deserves attention.

Weakness of Mainstream media

Recently the BBC Bangla Service ran a piece on the survivors and victims of the RanaPlaza disaster which struck thousands of garments workers and their families a fortnight before the massacre. When an editor was asked why the BBC Bangla Service were silent on the massacre and were not doing a similar piece on its victims, there was no reply.

With opposition figures like the ex-mayor of Dhaka Sadeque Hossain Khoka, who failed to protect the supporters in their time of most need, publicly pronouncing figures of several thousand dead, a distracting numbers game took hold, denuding the events of their meaning, commodifying and dismissing the deceased and bereaved in a way that even neoliberalism failed to at their point of ultimate witnessing. In New York, estimates of the dead in the TwinTowers attacks wildly exceeded the final human toll; a figure arrived at with time, full state backing, technical competence and freedom from recrimination.

David Bergman is a British journalist based in Dhaka, a go-to man for the international media because of his awkwardly challenging coverage of the war crimes trials. It transpires that despite being fed video evidence, chaperoned around hospitals and identifying at least 24 dead, he dismisses talk of massacre, preferring the more anodyne terminology of government brutality and an infectious double standards of evidence when it comes to the unworthy dead, whose names he cannot even spell correctly. Like many in Bangladesh, he preferred to play the lazy and tired motifs of religious vs. secular to his ill informed audience.

The Al Jazeera journey through Motijheel is worth analysing too, especially since their former Dhaka correspondent Nicolas Haque was successfully hounded out of the country by ultranationalists sensitive to his coverage of war crimes trials. The losing internal editorial battle at the once counter hegemonic Qatar-based station was rounded up by Shamim Choudhury’s cop-out fire brigade story and Jonah Hull’s inoffensive piece on media restriction.

Although small local weeklies, like the Dhaka Courier and Holiday covered the immediate aftermath, they soon fell silent through lack of capacity. Surely the agencies boasting specialist skills, global networks and institutionally funded to focus on human rights violations would do better?

The Human Rights Industry

In the business of human rights, there are worthy and unworthy victims. The worthy are deemed by the interests of donors and professional activists in any given situation. In Bangladesh, the performance of the sector and its practices are unaccountable in any meaningful sense, least of all to victims deemed unworthy of attention.

Global players in the sector like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch as well as the donors that fund their long term monitoring projects rely on local partners for information. Such gatekeepers are human and carry prejudices, competitiveness and consequent limitations. For example, the government’s performers of the year were Sultana Kamal’s Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), who took a good 10 days to publish a mealy mouthed condemnation of the victims.

The first substantive and official document came from Odhikar, a local competitor to ASK, on 10th June. It was largely ignored until the government failed to wrestle the victims list from them and arrested their secretary during the Eid period in August for ‘fabricating information’. This prompted an immediate US State Department intervention which made no mention of Odhikar’s documentation of the massacre. As indentured students of US diplomacy in these War on Terror times, we are reminded to reflect on the fact that this same department had just recently been training the Dhaka Metropolitan Police on tactical management of special events. With this additional exposure the pro government media quickly waxed lyrical over issues of Odhikar’s ‘faulty methodology’, as the police began leaking information, allegedly seized from the organisation, to the press.

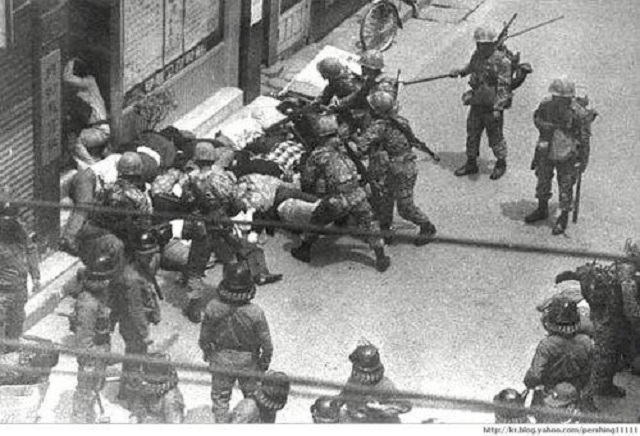

Odhikar has since been nominated for a number of awards by international partners in the human rights industry, but has failed to intervene further and publicly on the issue of this massacre, despite their leadership’s growing international stature. Interestingly, their recent Gwangju Award connects what happened at Motijheel with the Gwangju Massacre of 18th May 1980 in South Korea, in which the western-backed military dictatorship of the time brutally repressed an anti-regime uprising.

A scene from the 1980 Gwangju Massacre. (W. G. Sebald)

Back to Bangladesh and the New York-based Human Rights Watch published their own document, ‘Blood on the Streets’ on 4th August, referring to the massacre in sanitised terms, and bundling it in with the murder of a blogger, the Shahbag and War Crimes Trials. The report includes good snippets of victim testimony, but knowingly misframes the 6th May protesters to dehumanising effect.

The selective nature of this human rights work can be argued to be a function of local gatekeepers and sources, and organisational strategy. Though zealous in defending a self-image of independence and competence, a close reading of their reporting and a basic joined-up knowledge of their operations undermines this assertion. Crossing the government and interrogating official taboos like this massacre is a hazardous line of work, and we can recall one of HRW’s former Dhaka employees, the Daily Star journalist Tasneem Khalil’s torture by the previous military regime through three wikicables from mid-2007.

The domination of media and human rights sectors by people of very similar ideological leanings is problematic for politically diverse societies as it leaves large sections of the society vulnerable. The failure of the human rights industry to conduct itself with integrity and thoroughness is a lesson for Bangladeshis who crave dignity and access to justice to challenge it.

State repression of opposition media

One of the first questions people ask after pouring over the online archives of these events is ‘Why haven’t I heard about it?’ After explaining international donor disinterest, the disinformation campaign, an inept opposition and the marginalised status of the victims we arrive at the critical issue of media muzzling from the government. When a state crime has been committed, knowing about it and being willing and able to challenge authority can prove hazardous to the property, health and dignity of individuals and agencies without adequate power to defend themselves.

Key oppositional media organs have been paralysed by successive repressive measures from a regime whose mastery of manipulation would have impressed the late Stanley Milgram. His experiments explored the tendency for obedience to authority overriding basic morality. The events and dynamics of 2013 in Bengal and Nile deltas seem to extend his findings into new arenas.

Television is the prime source of information on national events in Bangladesh. On the morning of the attack, two private opposition owned television stations covering it live were shut down by the government for, in the words of Information Minister Hasanul Huq Inu, breaching ‘license conditions’ and ‘to maintain law and order’.

A month prior to the massacre, shortly after Hefazat’s first Long March, whose peacefulness and sheer size shocked the establishment, Mahmudur Rahman, the daily Amar Desh editor and owner, was arrested from his office having been confined there surrounded by police and intelligence officials for over a month. He was tortured and remains in detention on charges of inciting violence. His role in highlighting and mobilising opposition to religious insults emanating from the ultra-nationalist Shahbag movement has been applauded by supporters, and condemned by those who apportion him blame for the massacre. The gagging of his media organisation removes a key conduit for expressing the voices of witnesses and victim families.

Off with his head: Mahmudur Rahman (L) Amar Desh’s former editor, incarcerated and tortured for his campaigning editorial policy. St John (R), beheaded for denouncing King Herod’s tyranny.

The insecurity and insincerity of the remaining media came to the fore in the autumn when Farhad Mazhar, a prominent agriculturist and thinker was subject to vilification and state intimidation for articulating why the public would be angry at the media’s reckless and biased behaviour and voicing surprise that this legitimate grievance had not taken more physical form.

A state crime does not happen in a vacuum, nor as a consequence of one person’s poor decision, it is conducted through people, information and policies. Sustained scrutiny and issues of public accountability need to be raised regarding the roles of the domestic corporate press and international agencies, not to mention the human rights industry and social mediascape in this massacre. It is also important to hold to account the reliance of international agencies on a closed shop of native ‘misinformants’, whose limited talents are offset by their partisan, pro-government agenda and civil society camouflage.

Unheard Voices: An Interview with a Hefazat Leader and Survivor

Below we share a video interview, subtitled in English, with one of the survivors of 6th of May. Recorded in June 2013, it sought to understand better what happened that night, ask legitimate questions from a public too afraid to find out for themselves and answer allegations from the government camp. The interview challenges the government’s account of a 15 minute operation and the dehumanising war on terror discourse that has been spun around the victims.

The interviewee is a senior member of Hefazat e Islam and a popular performer of waaz, the Bangladeshi tradition of melodious religious exposition. He addresses a range of allegations made against the group, from the general anti-women’s development and Islamist accusations, to particular allegations of opposing war crimes trials and trying to bring down the government, as well as the surreal character assassinations of intentionally using children as human shields, looting and burning Qur’ans.

We hope this public witnessing will enable our journey to truth, societal justice, reconciliation and humanity, that it encourages more people to carefully record, explore and share their experiences of the May Massacre.

18 Questions for Hefazat e Islam from Motijheel Investigation on Vimeo.

An interview with Junaid Al Habib, protest organiser and a survivor of the Dhaka Massacre of 5-6 May 2013.

12 Comments

Militant Atheism, Madrasahs and Bangladesh: Midnight at the Noon of Golden Bengal | Nuraldeen

[…] the run up to and in the aftermath of the Dhaka massacre of May 2013, I asked Hefazote supporters as to the meaning of the 2nd point in their 13 point demand, and as to […]

Bangladesh: Let’s not hear it for the girls | Insideotherplaces

[…] many Islamists but equally has been happy to gun hundreds of them down mercilessly, as in the 2013 Motijheel massacre. Islamists have attacked and killed non-Muslims, particularly Hindus as they are seen as agents of […]

‘Who said this would be investigated?’ Bangladesh and the May 2013 Massacre | Progress Bangladesh

[…] Source: Ceasefire […]

[…] There is growing incredulity at the media and government machinations over Bangladesh coverage in recent years. Other important public interest issues are affected indirectly too. Many will recall the miraculous rescue of a young sewing machinist, Reshma Begum, 17 days after the Rana Plaza Garments Factory collapsed, it was reportedly a hoax (strenuously denied) used to manipulate the public mood and distract from the state crime that took place in Dhaka on 5th and 6th May 2013. […]

[…] new set of grievances and schisms for future generations to resolve. A vivid example of this was the massacre of unarmed, largely rural madrassa students protesting in Dhaka on 5-6 May 2013, and the surveillance, kidnap and financial persecution of persons from human rights group Odhikar, […]

[…] policy magazine Ceasefire has provided a very interesting insight on how the global actors and defenders of Human rights played their role. The excerpt is given […]

Flashback May 5: The Black Night at Motijheel and the Human Rights Industry | Kaagoj

[…] policy magazine Ceasefire has provided a very interesting insight on how the global actors and defenders of Human rights played their role. The excerpt is given […]

Flashback May 5: The Motijheel Mayhem and the Human Rights Industry – The FutureLaw Initiative

[…] policy magazine Ceasefire has provided a very interesting insight on how the global actors and defenders of Human rights played their role. The excerpt is given […]

The Shapla Square protests, or the Motijheel massacre, (also known as Operation Shapla or Operation Flash Out by security forces)[2] refers to the protests, and subsequent shootings, of 5 and 6 May 2013 at Shapla Square located in the Motijheel district, the main financial area of Dhaka, Bangladesh. The protests were organized by the Islamist pressure group, Hefazat-e Islam, who were demanding the enactment of a blasphemy law. The government responded to the protests by cracking down on the protesters using a combined force drawn from the police, Rapid Action Battalion and paramilitary Border Guard Bangladesh to drive the protesters out of Shapla Square,

The Shapla Square protests, or the Motijheel massacre, (also known as Operation Shapla or Operation Flash Out by security forces)[2] refers to the protests, and subsequent shootings, of 5 and 6 May 2013 at Shapla Square located in the Motijheel district, the main financial area of Dhaka, Bangladesh. The protests were organized by the Islamist pressure group,

Ap

Great

[…] There is growing incredulity at the media and government machinations over Bangladesh coverage in recent years. Other important public interest issues are affected indirectly too. Many will recall the miraculous rescue of a young sewing machinist, Reshma Begum, 17 days after the Rana Plaza Garments Factory collapsed, it was reportedly a hoax (strenuously denied) used to manipulate the public mood and distract from the state crime that took place in Dhaka on 5th and 6th May 2013. […]