Why is Tibet Burning? A reflection on the self-immolations of Tibetans Comment

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Tuesday, February 28, 2012 5:01 - 3 Comments

By Anna Alomes

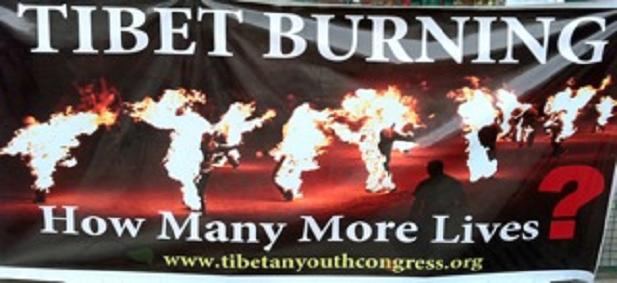

Protest banner in Dharamsala, India where the Dalai Lama has the Tibetan seat of Government in exile. (Photo: Anna Alomes)

Two items on the table in front of me create tension and confusion. A DVD gifted a few days back which records public conversations by His Holiness the Dalai Lama called “Happiness, Life and Living” and today’s newspaper headline which reads “Another Tibetan Chooses Death by Burning”. Urgent questions arrive via email: “Is this action nonviolent?” Before we can begin to make a judgment on that question, we need to first backtrack and determine what is actually happening here. What are the causes of this action? What does it mean and what are the hoped-for outcomes? Only when we do that, can we even begin to unravel the complexity.

The first thing to be said is that no one should suffer and no one should set themselves on fire. The 23 young Tibetans who have suffered this fate at their own hands are predominantly monks or nuns or ex-monks or ex-nuns. (Recently, 3 Tibetan farmers and a young Tibetan lay-person also joined the immolation activity). So they know exactly what the Tibetan philosophical and spiritual position is and they know in precise detail the consequences of their actions. You may not take a life. You may not harm anything. You are required to act for the benefit of others. But they would say that’s exactly what they’re doing.

The second thing to be said is that no one should be illegally detained, beaten with spike-laden clubs, electrocuted, raped or murdered. We know from Human Rights reports and first hand witness accounts that this has been happening to Tibetans under Chinese occupation for more than 50 years. Cultural genocide is the reality to be endured by Tibetans on a daily basis. They have tried routine nonviolent protest (gathering together, displaying written objections, undertaking civil disobedience) for decades.

Torture and death is the result for any action that we may take for granted as our basic civil right (documented by Amnesty International among others). Tibetans are insisting that the genocide must stop. Nothing seems to be working, so a proportion of the community changed their mode of action. They are compelled to act to stop other Tibetans from suffering and to stop the Chinese authorities from spiraling even further down the unmeritorious slippery slope.

The self-immolations are beginning to stimulate debate on social media networking sites with a variety of opinions offered attempting to explain the behaviour. Some say it is copy-cat strategic action – copying the Vietnamese Buddhist monk who self-immolated to protest persecution. In 1963, Thích Quảng Đức, a Vietnamese monk set fire to himself at a busy Saigon intersection. The famous Pulitzer Prize winning photograph by Malcolm Browne of the burning monk sitting serenely in the lotus position surrounded by flames, became a worldwide sensation and contributed to fall of the Diem regime. Likewise, copying Tunisian vegetable merchant, Mohamed Bouazizi (2010), whose act of self-immolation inspired protests that fanned the winds of the Arab Spring and led to the toppling of the Tunisian government.

Others offer that its origin can be found in The Lotus Sutra (Tib. dam chos pad-ma dkar po’i mdo) – one chapter of this sutra recounts the life story of the Bodhisattva Medicine King who demonstrated his insight into the selfless nature of his body by ritualistically setting his body aflame, spreading the “Light of the Dharma” for twelve hundred years.

Others offer that its origin can be found in The Lotus Sutra (Tib. dam chos pad-ma dkar po’i mdo) – one chapter of this sutra recounts the life story of the Bodhisattva Medicine King who demonstrated his insight into the selfless nature of his body by ritualistically setting his body aflame, spreading the “Light of the Dharma” for twelve hundred years.

Others say that a Chinese propaganda film aimed at winning Tibetans towards the state may have backfired: Red River Valley (Ch. Hóng hégŭ) a 1997 film was little seen outside the mainland, and depicts Tibetans bravely struggling against the British invasion around the turn of the century. Towards the end of the film, the Tibetan hero wins the battle for the Tibetans by setting himself on fire while overcoming the British battalion.

Time magazine elevated the issue to most underreported story in 2011 and Time reporter Hannah Beech called the actiona “new, nihilistic desperation [that] has descended on the Tibetan plateau.” Regardless of whether we think the despair of the young Tibetans who set themselves on fire was informed by historical accounts of others undertaking this action (in life or film) or religious texts, there is no getting away from the fact that it is a last ditch act of desperation and when you ask them what they are in despair about they say the intolerable conditions exercised by the Chinese government inside Tibet. A last resort action by young people who feel they have nothing left to offer but their own lives, in order to force change in an unbending political structure.

As a people, Tibetans carry the legacy of nonviolence as their duty. They cannot take a life, but they can give up a life. Perhaps they feel liberty in death is the last freedom open to them, and they have pursued it, in flames and in the public arena. They have done this in order to catch the Chinese attention and the world attention and to say “STOP”. As they believe in karma they technically must bear the consequences of their action – even if the consequences are minimized by the altruistic intention already named, it is also part of the belief system that you cannot commit suicide. These 16 Tibetans have weighed up the consequences and have acted anyway. Is the action violent? Is it nonviolent?

On the Tibetan Buddhist view violence is born out of anger, hatred and ill-will driving intentional harm. All 23 people involved have claimed an insistence on truth, demanded the cultural genocide stop, demanded access to their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama and calmly set themselves on fire. The action doesn’t satisfy the Tibetan criteria for violence. On their own terms it can be viewed as nonviolent, but it does breach their own rule regarding the abhorrence of suicide.

On the Tibetan Buddhist view violence is born out of anger, hatred and ill-will driving intentional harm. All 23 people involved have claimed an insistence on truth, demanded the cultural genocide stop, demanded access to their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama and calmly set themselves on fire. The action doesn’t satisfy the Tibetan criteria for violence. On their own terms it can be viewed as nonviolent, but it does breach their own rule regarding the abhorrence of suicide.

From an observer’s viewpoint, no one should set fire to themselves and no one should endure such suffering and despair that they feel the only recourse left to make change in an unbending an intolerable system is to set fire to themselves (and apparently hundreds more have pledged to do just that). We can’t call ourselves civilized if we stand by and watch them do this and all we do in response is to ask if this action is nonviolent.

That after all was the question. We also can’t call ourselves civilized if we stand by wringing our hands, concerned about the economic bottom line if we interfere in the sovereignty of a nation state busying itself with genocide.

One thing however is certain: the basic building block of a “civilized society” is an insistence that governments have a responsibility to protect citizens–recall that the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) principle is a new international security and human rights norm stating that governments who abuse their citizens, commit systematic human rights violations, or engage in genocide forfeit the protection of their sovereignty. The R2P principle has not yet been invoked by the international community on behalf of the Tibetans. However, if the 21st century has the potential to be the century that ends the sanctioning of violence, Tibet should be at the heart of ours efforts.

3 Comments

Thank you for the interesting contrast of “taking a life” versus “giving up a life.” It never ceases to amaze me how language limits our imagination – thank you for reflecting on this reframing and making it accessible to us.

John Schooneveldt

As China rightly seeks to become a global influence for good in the economic, environmental and social domains it will need to deal with the moral issue of Tibet.

Can the world do more than express shock and horror? Maybe not. It is now up to China to demonstrate that it is worthy of being recognised as a civilised nation.

How insightful. Ms Alomes has succinctly summed up what so many, many of us are thinking. When will the world act!