Review: ‘Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere’ by Paul Mason Books

Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Tuesday, January 10, 2012 12:54 - 1 Comment

By Alex Baker

In a year where many reporters wore bullet-proof vests to travel through Hackney during the August riots, Paul Mason, BBC Newsnight’s economics editor, appeared on the streets of Greece and Cairo with, more often than not, only a borrowed gas mask for protection. Of course, Mason knew that he had comparatively little to fear: he has been one of a few mainstream reporters to actually interview, and attempt to understand, the social movements and forces that have grown since 2009. As such, Mason’s presence has ironically become itself an omen of things ‘kicking off’. Planning a march? Banners? Check. Callout? Check. Coaches sorted? Check. Unions on board? Check. Student Bloc? Check. SWP placards? Check. Paul Mason here? Check. Lets do this.

In a year where many reporters wore bullet-proof vests to travel through Hackney during the August riots, Paul Mason, BBC Newsnight’s economics editor, appeared on the streets of Greece and Cairo with, more often than not, only a borrowed gas mask for protection. Of course, Mason knew that he had comparatively little to fear: he has been one of a few mainstream reporters to actually interview, and attempt to understand, the social movements and forces that have grown since 2009. As such, Mason’s presence has ironically become itself an omen of things ‘kicking off’. Planning a march? Banners? Check. Callout? Check. Coaches sorted? Check. Unions on board? Check. Student Bloc? Check. SWP placards? Check. Paul Mason here? Check. Lets do this.

The author of Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere has not set himself an easy task: attempting to understand the reasons why 2011 was a year in which dictators fell, civil wars broke out, the integrity of the press called into question, the Eurozone spiralled out of control, and popular social movements set the agenda for the first time in over 20 years.

In this ambitious endeavour, Mason draws upon a blogpost of a similar title, written in February of 2011, in which he spelled out a list of 20 factors behind the Arab Spring, Student Riots and Greek chaos. It was an instant hit and proved to be remarkably prescient considering what was to happen for the rest of the year. Mercifully, the book has whittled things down from 20 reasons to roughly three: new technologies, the networked forms of organising they facilitate, and the emergence of the ‘graduate without a future’. The result is a gripping but informative introduction to a global and enormously varied political movement.

Reading the book, it becomes quickly clear that what we are hearing is a powerful old tune played on a brand new instrument. ‘The graduate without a future’ is a particular form of labourer, one who has been given an education in Marx and Foucault, promised a job, yet is now being told she must accept worse pay and conditions than her parents, or in the case of countries like Greece and Spain, that no jobs are available at all.

It was, arguably, a similarly betrayed and angry middle class that sparked the movements of 1848. For Mason, the ‘GWAF’ is not a get out clause to help us avoid the challenge of class inequality, as some would have us believe- instead it means we have to account for this challenge directly as the old certainties collapse. The effect when these elements encountered the urban poor has been explosive, we are told in exhilarating prose; when the black bloc smashed shop windows in late March of last year, argues Mason, the residents of the ‘British Banlieue’, the youth of Hackney and Tottenham, were there, watching.

Talk of ‘twitter revolutions’ and ‘network power’ abounded in 2011, to the extent that one could almost be convinced that a Greek or Egyptian somewhere had logged in to find a revolution-themed lolcat and thought: “right, popular struggle against state power it is”, as though it had never occurred to them before. Thankfully Mason’s approach grounds these concepts in the lived experience of the people he interviews; from the garbage pickers in the backstreets of Cairo to the UCL occupier who voted Lib Dem in 2010. It is social interactions that brought us these technologies and the movements they have inspired. The use of twitter names in print is at first odd, but then to what extent is this a re-inventing of the old revolutionary practice of the nom de guerre; like writing ‘Lenin’ or ‘Che’ at the end of a letter?

At times, Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere threatens to succumb to a macho political narrative; a term like “kicking off” conjures up as much a pub brawl as a political struggle. Beneath every riot, every occupation, and every march, there are a whole series of conflicts about the personal and the domestic that can get overshadowed in this book. Though keen to note where women have formed the ‘backbone’ of the social movements, issuing the public statements and doing the organising, Mason might have done more to question how and why this situation has come about.

In a context where riots and mass direct action have become part of the political toolbox, it’s worth questioning the extent to which the necessary but often boring processes of organising and public statements – and the people who do such roles – have become less visible. In this sense Mason’s journalistic style is both his strength and his flaw; an excitement abounds that sometimes papers over the cracks in its subject matter.

This is most visible when Mason occasionally veers into over-emphasising the more magical aspects of the thinking behind social movements. Despite giving us a helpful caveat that his work is journalistic, not academic, Mason’s understanding of the ‘network’ could have been fleshed out more, especially as this form of organising has been hotly debated by participants in social movements in recent years.

Concepts like the ‘Temporary Autonomous Zone’ and ‘being the change you want to see in the world’ are no longer the givens they once were. Networks, as Gilles Deleuze argued in his provocative ‘Postscript on Societies of Control‘, can be as hierarchical and coercive as pyramidal models of organization. Nonetheless, where pressed for space Mason is careful to reference the broader literature, and indeed Deleuze, along with the likes of Manuel Castells and ‘Bifo’ Berardi, all get a mention. Moreover, the thrust of Mason’s argument- that the old ideologies of Leninism, strong hierarchies, party-politics and central committees seem distant to today’s protesters- remains intact.

Before the global financial crisis, being on the political left in the UK was often a disheartening experience; seemingly a case of perpetually helping in someone else’s struggle. Indeed, whenever the left looked for inspiration, it generally came from distant stars: Porto Alegre, Palestine, Chiapas, Cochabamba, wherever the latest G20 was. Despite the dire warnings it uttered, when the crisis came the left still seemed taken by surprise and is still trying to find its feet.

Why Its Kicking Off is a timely reminder that the devil is also on our own doorstep and that we face the starkest of choices; between a more socially just system, or the lights going out all over Europe again. This isn’t a difficult book to understand, and it’s hard to think of a better introduction to the political zeitgeist and social movements of our age. As any good Marxist will tell you: Paul Mason is an economics editor, but he is also a war correspondent. It’s just been a while since the two were so visibly one and the same.

Why Its Kicking Off is a timely reminder that the devil is also on our own doorstep and that we face the starkest of choices; between a more socially just system, or the lights going out all over Europe again. This isn’t a difficult book to understand, and it’s hard to think of a better introduction to the political zeitgeist and social movements of our age. As any good Marxist will tell you: Paul Mason is an economics editor, but he is also a war correspondent. It’s just been a while since the two were so visibly one and the same.

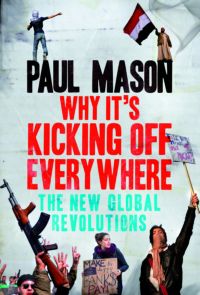

Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere

Paul Mason

Verso (2012)

Paperback, 221 pages

1 Comment

Amy

But what Mason has closed his journalistic door to, while he’s singing the praiseof revolutionaries, is the provision being made in the EU’s international trade agreements for the ‘graduates without a job’ to come to the UK and thus ensure that there are many more ‘graduates without a job here’.

This is something that the very many UK ‘graduates without a job’ might think it’s the ‘job’ of BBC-paid (i.e. publicly-paid) journalists like Mason to tell them.

But I guess such factual inclusion doesn’t fit the narrative or the image, and will not help sell books to ‘radicals’..

So let’s not allow truth to get in the way of these higher aims.

This is the situation re ‘graduates without a job’ from outside of the EU. ‘Graduates without a job’ from within the EU, e.g. high unemployment Spain, are already flooding in. Perhaps Mason is too busy with the next book deal to notice. Or – again – doesnt want to talk about it…