The Right of Return: the question that will not go away West Bank Diary

New in Ceasefire, West Bank Diary - Posted on Sunday, January 27, 2013 16:42 - 0 Comments

By Derek Oakley

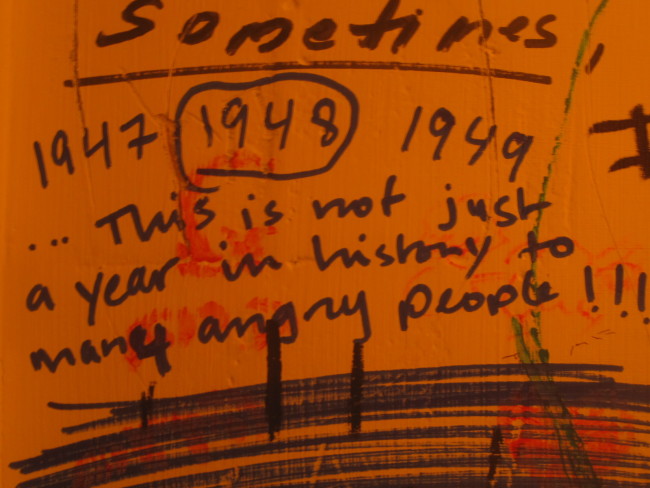

Graffiti in the toilet of a bar in West Jerusalem

Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country. -Article 13(2), Universal Declaration of Human Rights (10 December 1948)

Mary is 75, the archetypal sweet grandmother welcoming me to take a seat next to her on the bus with a thick Brooklyn accent and a disarming smile. She retired 8 years ago, moving away from busy city life in the US (“It’s for the young people”) with her husband to a more relaxed locale with a higher quality of life. A pretty typical story, the difference being that Mary chose to move from New York to the settlement of Ariel in the occupied West Bank.

A few days later in Nablus I meet Amina and her mother Aisha. They are Palestinian refugees whose family spent decades in Jordan until returning to the West Bank around five years ago. Amina has just returned from studying Human Rights Law in the USA. Her father was a senior PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organization) official and, despite her Jordanian upbringing, she considers Palestine her home.

Over a typically hospitable Palestinian lunch packed with fresh vegetables and hummus (and liberally seasoned with the national herb Za’taar) Amina fondly remembers her grandmother talking for hours about their home village of Al-Ludd, now Lod, in the modern state of Israel – the state from where the majority of the Arab population were expelled by Jewish forces in 1948 during what Palestinians call the Nakba (‘Catastrophe’).

Mary and her husband made Aliyah (Hebrew for ‘Going up’ to Israel) in 2004, taking advantage of the Israeli Law of Return that was passed in 1950 that extends the right of settlement and citizenship in the state of Israel to all Jews.

Mary and her husband made Aliyah (Hebrew for ‘Going up’ to Israel) in 2004, taking advantage of the Israeli Law of Return that was passed in 1950 that extends the right of settlement and citizenship in the state of Israel to all Jews.

In 1971 the law was amended to expand the provision of this right to people of Jewish ancestry and their spouses. They elected to move to Ariel, which was founded in 1978 and given city status by the Israeli government because it is “cheaper and more comfortable than somewhere like Tel Aviv”.

She believes that not all ‘Arabs’ are bad but “most of their leaders are” and that this is the major obstacle to peace for Israel. She is disappointed that her adult children have not chosen to join her in Ariel.

Amina, her mother, and the rest of their family, have an inalienable Right of Return to their home, as stated in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and detailed with specific reference to Palestinians displaced in 1948 and their descendants in numerous UN Resolutions, beginning with UN General Assembly Resolution 194, which presents a clear plan for implementation of the right of return by Israel and was specifically referenced in Resolution 273, which documents the admission of Israel to the UN.

This right is also enjoyed by the additional Palestinian refugees created by the 1967 conflict between Israel and Arab countries. Israel has never implemented this plan, or subsequently recognized or committed to the right of return for the now estimated 5 million Palestinian refugees in the occupied territories and the diaspora. If all such refugees were to claim their right today, the practicalities of facilitating this would be mind-boggling.

The Right of Return sits at the heart of Palestinian politics, and any debate of it, such as that prompted by Mahmoud Abbas earlier this year about his own relationship to his hometown, is always sure to be heated.

My new acquaintance Mary didn’t acknowledge in the course of our 20 minute conversation the existence of Palestinian national identity or right to a state, let alone the Right of Return. In fact the word Palestine, or Palestinian, are notable by their absence. A clue as to why comes when I use the word ‘occupied’ and she stops me to offer a correction “Well, we should at least say ‘disputed’ and I would even say ‘liberated.”

That is to say that for Mary, the whole of the occupied Palestinian territory beyond the 1967 armistice line, is part of Israel. This would go some way to explaining why she lives in Ariel which, regardless of its recognition by or support from the Israeli government (for example on Christmas Eve Ariel College was officially upgraded by the state to university status, drawing condemnation from the UK government amongst others) remains illegal under international law.

Amina, whilst having no lost love for Israel, accepts the parameters of the 1993 Oslo Accords as a starting point for peace, including the recognition of the State of Israel. She is not prepared though, to advocate against or disavow the right of return for her family to their ancestral lands, lands that sit squarely within Israel. As with many Palestinians, however, she may well not seek to realize that right in practice.

Lod still exists, and has a sizeable Arab minority, but many Palestinian villages from 1948 have long disappeared. Nonetheless the recognition of this right feels integral to the Palestinian vision of peace and justice, something that the exclusion of Palestinians from Mary’s worldview would seem to put a long way off. As Desmond Tutu wrote earlier this year

“We cannot afford to stick our heads in the sand as relentless settlement activity forecloses on the possibility of the two-state solution.

If we do not achieve two states in the near future, then the day will certainly arrive when Palestinians move away from seeking a separate state of their own and insist on the right to vote for the government that controls their lives, the Israeli government, in a single, democratic state. Israel finds this option unacceptable and yet is seemingly doing everything in its power to see that it happens.”

And even if such calls were to be heeded and two state solution resurrected and realized, the right of return would remain. What would happen to Mary and Amina? How can their realities and their visions of ‘Home’ be realized in a manner that is just, peaceful and consistent with international law? Israel systematically refuses the Human Rights of Palestinian refugees around the world while creating a ‘two tier’ system of law for those Palestinians under its control, privileging the likes of Mary over Amina.

As long as the voices of Amina and those like her are heard, hope for justice will not be lost, but it feels like a long road ahead.

[This article draws upon two real life encounters but names have been changed to preserve anonymity.]

Leave a Reply