Must the Wretched of the Earth Be Moral? Revisiting Fanon on Violence Comment

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Tuesday, December 9, 2014 23:59 - 4 Comments

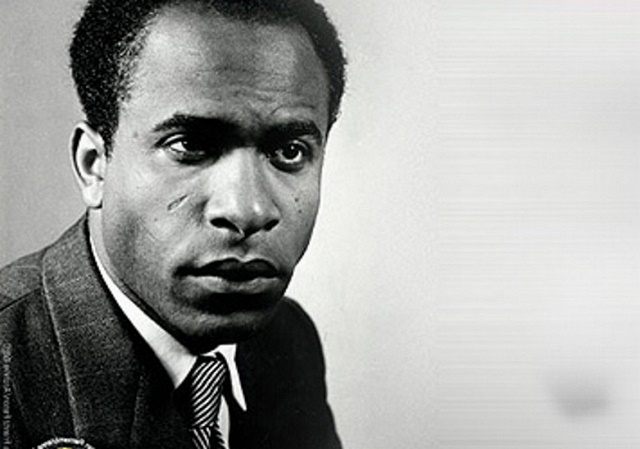

Over the centuries, European Terrorism has not only been manifest in its material impact (war, neo-liberalism, environmental degradation) but also in the equally-destructive psychological aberrations it engenders (inferiority, self-hatred). That was the central theme of Frantz Fanon’s 1961 classic, Les Damnés de la Terre, (The Wretched of the Earth). The drastically asymmetrical dynamic of the master-slave/coloniser-colonized/bourgeois-proletariat relationship operated in both realms, the physical and the psychological, and meant that this violent asymmetry could – and would – be maintained in absentia by convincing former slaves that they still needed their masters, whether it was for the extortionate rebuilding of their liberated land, to bring about ‘democratisation’, or, in an increasingly globalised world, to export the master’s more ‘enlightened’ and free culture.

Observing people’s attempts to organise, mobilise and emancipate themselves, it is evident they are motivated by a sense that not only must the material world be made more equal, but that the body and consciousness are also engaged in this struggle for freedom. However, from our position of relative comfort, many of us in the West are often agitated when we see moral slip-ups, lapses of virtue, offences to our sensibilities, that are committed by people resisting such oppression across the world; and a difficult question arises: Do the oppressed have an obligation to be moral?

Struggles may take place both in war and in peacetime, though ‘peacetime’ is almost always a misnomer in a world where foreign occupation and ‘humanitarian intervention’ often sit side by side with the slow-death of austerity, racial struggles, police brutality, and the psychological abuses of which Fanon spoke, which bleed into all arenas of our life. When we, in the ‘west’ join up in the name of sister-brotherhood to interconnect and communalise our struggles, we come under criticism when our comrades flout universalised norms of conduct. Internationalism is compromised when the IRA bombs shopping centres, Hamas fires rockets into Israel, or students cause ‘mindless damage’ at Millbank.

In this context, could one consider the idea of a temporary moral suspension? This would invite us to consider ‘understanding,’ as a precursor and prerequisite to ‘moralising’. Rather like the hermeneutical tradition, we may seek not to condemn or condone actions exclusively, but to interpret and understand them. To ‘understand’ in the sense described here is very much a historicized endeavour, though one that deviates from ‘objectivising’ tendencies. I’m referring here to the Romantic Hermeneuticists who sought to determine the ‘one’ meaning of a text through authorial intent. Instead, we ought to try to acknowledge the situated-ness and temporality of the ‘oppressed-transgressor’.

As such, this is an effort, an exertion on ourselves, in the pursuit to understand, to comprehend the ‘prejudices’ of others (which we similarly have) and how their own histories have coloured their presents. The object of understanding, consequently, becomes the act but situated within a history that gives it meaning. In this context, Gadamer – often accused of adopting an inherently conservative theory of understanding – can be read through a radically different and progressive lens. For instance, Gadamer claims that we are trapped by our prejudices, by our ‘effective histories’ which will necessarily seep into what we do and say.

To understand ‘immorality’ is to place it back into the interpentrativeness of life, its inherent connectedness with past, present and future. It forces us to intuit (but not to validate- an entirely different matter) as to why the suicide bomber sacrifices his body, why the resistance fighter targets civilians, why the phenomena of ‘immorality’ occurs.

Reconfiguring understanding-moralising in this way, what do we see? In ‘The Wretched of the Earth,’ Fanon writes:

‘At the individual level, violence is a cleansing force. It rids the colonized of their inferiority complex, of their passive and despairing attitude. It emboldens them, and restores their self-confidence.’

Though violence can be ‘moral’ as well as immoral, such method of determination tends toward moralising first before understanding, if at all. But Fanon’s words have a deeper resonance in which this interpretation of ‘immorality’ could be seen as a cathartic liberation of the soul. Understood this way, emancipatory movements, whether in the shape of anti-colonial forces or the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, were not about showing compliance with universal moral norms, but represented surges of a collective, repressed spirit bursting forth against its aggressor.

We are resistant to such interpretations, however, because of our predisposition towards preferential moralizing universalism. The social sciences, particularly in the post-modernist era, have all but marginalised the rational actor model. Whether it’s Althusser’s de-centering of the self or Lyotard’s micro-narratives, what they strive to understand is that the self is not privileged like the ‘rational agent’ of the enlightenment, foisted upon us by the universalist project of rich white men. The self is contingent, temporal, changing. It is not merely constituting but constituted.

Do we descend, therefore, uncontrollably down a slippery slope in which everyone is absolved and no one is accountable? You may be disappointed to learn that I am unable to provide any succinct or ‘practical’ answers, opting instead to quote Gilles Deleuze: “philosophy is at its best in critique, an enterprise in demystification”. Perhaps what concrete lessons can be taken from this reflection is that understanding provides us with a clearer vision for subsequent ‘moralizing’. It places peoples and their struggles in their appropriate temporal contexts, instead of fixing them into an isolated present of action.

Without this necessary contextualising effort, the act of moralising would amount to little more than infantilising. Indeed, though I (Bangladeshi Diaspora, working class trying to make it in a field where my kind are massively underrepresented) would consider myself in some respects belonging, or certainly sympathetic, to the ‘Wretched’, the title of this article – with its patronising use of the ‘we’ – leaves me uneasy. For whoever this ‘we’ is, must validate such questions of morality.

Premature moralising subjects the persecuted to the blind assumption of liberal equality. As such, to moralise against those in the struggle, without the necessary effort of reflection that such moralising demands, would be to adopt the same presumptions of superiority that were so eloquently unmasked and condemned by Fanon himself.

See Also: Frantz Fanon: Fifty Years On

4 Comments

Ed Yates

E

This article was recommended as being on a similar topic.

Sarah Kheder

Excellent article!

This is an excellent piece – some very important reflections on Wretched which unfortunately is often misunderstood. I’m interested in how narratives about violence often change with time, with UK counter-terrorism narratives now explicitly stating that the violence of the IRA was different than that of Muslims today. Extending that further, editorials in major media outlets are beginning to acknowledge that the violence of the Islamic State is different than that of the Taliban or al-Qaeda central. Although, bizarrely, this narrative while acknowledging the temporal and spacial differences between these groups, situates that violence within a liberal discourse that continually fails to place grievance within the narrative. Hence, their response to each of these ‘threats’, within their own time periods, ends up being a cyclical repetition, i.e. “we’ve never faced a threat like this before”, thereby resulting an ever increasing security narrative which undermines communities, rather than dealing with root causes. Once again, very much enjoyed reading this – thanks.

I completely agree with one of the premises of this piece, namely that we should reject the notion of there being a universal morality that we should aspire to (this is what I take your comment about ‘preferential moralizing universalism’ to mean). Generally, whenever recourse is made to this universalising morality it is made by the strong against the weak. The Second Iraq Invasion was moral according to Western elites, but not according to the Iraqi population or others in the region.

But this does not mean that the oppressed should not be moral. It means that they must adopt a radical, emancipatory morality. I believe that this article alludes to this without perhaps saying it explicitly. Although, perhaps it does not. You quote Deluze in saying that the best philosophy can do is critique and demystify. I would argue that philosophers and academics more generally have a duty to offer more than mere critique; their favorable position in capitalist society means that there is the potential they will be listened to more. This idea bring in ideas of praxis and Gramsci’s idea of organic intellectual which is straying somewhat from this topic, so I will not continue along those lines. I will end be re-stated my agreement with your rejection of hypocritical liberal notions of equality.