What we can learn from Black Power

Features - Posted on Saturday, April 26, 2008 18:05 - 7 Comments

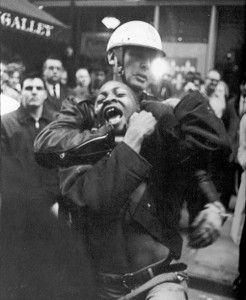

The Black Power movement is often portrayed today as an unfortunate, militant and violent byproduct of the struggle for civil liberties in America during the 1960s.

Musab Younis examines Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (1967) by Stokley Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, and finds a call for genuine democracy and an appeal to grassroots activism that we could do well to learn from today.

It may seem odd to review a book that was published in 1967 and is now (shamefully) out of print. But in less than 200 pages, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, written by Stokley Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, virtually decimates any book published recently in terms of perception, understanding and potential. Its significance is difficult to overstate, and certainly impossible to adequately convey in one article. It is a fiery and impassioned call for the most oppressed group in America – those descendants of slaves, brutally and violently kept in a position of subservience and dependence for hundreds of years – to rise up and claim freedom through political action. But it is couched in the language of the anti-colonial struggle, and at its heart it explicitly seeks the freedom of all people, and the establishment of real democracy and independence around the world.

Regaining Control

Black Power was published two years after the assassination of Malcolm X and one year before the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. A growing public outcry about the Vietnam War was taking place, with hundreds of thousands of people demonstrating across America. Muhammad Ali refused his draft in the same year, and was stripped of his title and jailed. The ‘long hot summer’ of race riots in American ghettos, echoing frustration at grinding poverty and racism, was underway. Years of passive, peaceful resistance had led nowhere; many were becoming increasingly radical, inspired by worlwide events. The lengthy period of European colonisation of the Third World was finally ending, following long and bloody wars of independence. The first generation of independent, post-colonial leaders in Africa and Asia was emerging. Change was in the air, and everywhere. In this context, Stokley Carmichael and Charles Hamilton set forth a radical blueprint for the ending of racial problems and freedom for the oppressed of America. They had one simple, revolutionary idea: Black Power. The genuine emancipation of black people, they said, would come from the throwing off of American institutional racism, ingrained in the political and economic system for hundreds of years. “Black people,” said Carmichael and Hamilton, “must get themselves together.”

The authors were well aware of hostility to their ideas. “When the concept of Black Power is set forth,” they note, “many people immediately conjure up notions of violence.” But their aim, as eloquently explained and studiously referenced, was the political organisation of an oppressed, persecuted and exploited group, with the aim of attaining genuine control over their own lives. “If we fail,” they state emphatically on the first page of the book, “we face continued subjection to a white society that has no intention of giving up willingly or easily its position of priority or authority,” but “if we succeed we will exercise control over our lives, politically, economically and physically.” This search for genuine freedom and autonomous development was intimately connected to the anti-colonial struggle and literature of the time. “Black Power means that black people see themselves as part of a new force, sometimes called the ‘Third World’ … we see our struggle as closely related to liberation struggles around the world.” Everywhere, “black and colored peoples are saying in a clear voice that they intend to determine for themselves the kinds of political, social and economic systems they will live under.” The choice of quotations early in the book is indicative: Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Frantz Fanon. The latter’s Wretched of the Earth is one of the book’s major inspirations, and provides a quotation that needs no adjustment to bring it up to date: “We do not want to catch up with anyone. What we want to do is go forward all the time, night and day, in the company of Man, in the company of all men.” As with the struggle for freedom in Africa and Asia, it was recognised that freedom is not a gift bestowed by the powerful, but a right won through action and organisation. “Left solely to the goodwill of the oppressor,” they state, with a dry wit that permeates the text, “the oppressed would never be ready.”

Inspired by this new understanding of the colonial situation, Carmichael and Hamilton see the situation of black people in America as intrinsically colonial; not simply a poor minority, black people are an institutionally oppressed group. Quoting The New York Review of Books, which described the situation of black people in America as “an instance of internal imperialism”, they explain that “there is no ‘American dilemma’ because black people in this country form a colony, and it is not in the interest of the colonial power to liberate them.” The economic subjugation of black people in America – like working long days picking cotton in order to be able to afford to buy cotton dresses from whites – mirrored the relationship of African and Asian colonies with the white, colonial powers. The exploitation of labour and resources in the ghetto was seen as an explicitly colonial relation, and when the exploiters arrived with messages of goodwill, they were no different to the missionaries who participated in the “economic deprivation” of Africa. “As in the African colonies,” say Carmichael and Hamilton, “the black community is sapped senseless of what economic resources it does have.” They articulately document the poverty and social alienation in the ghetto; little of the situation is, unsurprisingly, out of date. Carmichael and Hamilton also find echoes of colonial ‘indirect rule’ in the relationship of the white establishment with local black leaders. They see the co-option of black elites into white power structures as identical to the process that occurred in African and Asian countries under colonial rule. Their argument is forceful, and convincing. When tokenism was widely heralded as the way forward, Carmichael and Hamilton saw the few black political leaders as little more than African chiefs submitting to colonial rule: “They have capitulated to colonial subjugation in exchange for the security of a few dollars and dubious status”; they cannot hope to challenge the colonial status of the system itself. The assertion that “black visibility is not Black Power” sounds almost prophetic today.

Institutional Racism

Black Power is perhaps most well-known, at least in Britain, for coming up with the term ‘institutional racism’: “When white terrorists bomb a black church and kill five black children,” explain Carmichael and Hamilton, “that is an act of individual racism, widely deplored by most segments of the society.” But when, in the same city – Birmingham, Alabama – five hundred black babies die each year because of the lack of adequate food, clothing and shelter, “and thousands more are destroyed and maimed physically, emotionally and intellectually because of conditions of poverty and discrimination in the black community,” – that, the authors point out, “is a function of institutional racism”. The phrase crash-landed on British soil with the Macpherson report published in 1999 after the inquiry into the death of Stephen Lawrence, castigating the Metropolitan police for ‘institutional racism’ using a definition virtually identical to Carmichael’s (Black Power was the major work referenced in the report.) And the method of institutional analysis adopted by Carmichael and Hamilton, who examine with real methodological thoroughness the structures of oppression in America, contributed to a tradition that has informed the work of countless thinkers (most notably, perhaps, that of Noam Chomsky). But Black Power is not just a conceptual call to arms and freedom – it documents the exciting and challenging attempt to engage genuine participation in the political system of America and the terrific racism and resistance that faced this struggle. About half the book is dedicated to documenting on-the-ground struggles for political organisation and mobilisation. One chapter describes the voter registration drives of Lowndes County, Alabama (a majority-black county where eighty-six white families owned ninety percent of the land) with an infectious passion and real narrative drive.

Little has changed since Black Power was published forty-one years ago. At that time, the percentage of black children in America born into poverty was 43 percent. Today it is 45 percent. The income of the poorest black households has actually decreased since the mid-sixties. And so on, across the world. The search for genuinely democratic forms of government continues, with renewed strength. The increasing poverty, alienation and desperation of most of the world’s population is well known, and the activist movements of today could learn countless lessons from the call to independence and democracy in Black Power. When many people saw the future of black people as integration into middle-class America, Carmichael and Hamilton rejected this vision – “the values of that class are in themselves anti-humanist,” they declared. Instead, they called for the reorientation of the values of American society. This was to be “an emphasis on the dignity of man, not on the sanctity of property.” It meant “the creation of a society where human misery and poverty are repugnant to that society”; a society based “on ‘free people’, not ‘free enterprise’.” To do this, stated Stokley Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, meant “to modernize – indeed, to civilize – this country”, and work for “the move toward the development of wholly new political institutions.” And today, across the world, many seek the civilising of society; the dismantling of illegitimate authoritarian structures and the rebuilding of democratic ones. Carmichael and Hamilton realised in 1967 the difficulty of the task ahead. Gaining freedom means that “jobs will have to be sacrificed, positions of prestige and status given up, favors forfeited.” Co-option into oppressive institutions is simply not an option. In fact, “it may well be – and we think it is – that leadership and security are basically incompatible.” After all, they incisively explain, “when one forcefully challenges the racist system, one cannot, at the same time, expect that system to reward him or even treat him comfortably.” There remain many who dismiss the struggle for genuine democratisation and freedom as utopian and unachievable, and it would be fitting to end with a final word from this important book: “If all this sounds impractical, what other real alternatives exist?”

7 Comments

Good writing of a timely cover-article though I would say Steven Lawrence was a long time ago, and local government did listen and provide training on how to work with institutional racism. The problem is now we face globalised resistance.

Ceasefire I owe you much more than 50p.

Though white, I sincerely hope Ceasefire will plug my campus action website the address of which is edited out of my latest article in Impact about white man’s better living through shiny black power that is ‘clean coal’. My blog is powered by blog-city, but with RSS input and output to allow for syndication.

I’m now an online subscriber so won’t have to nail or otherwise defend any trees any time soon.

a non

i own this book, hadn’t realized it was out of print. a true shame. this book should be liberated (scanned,etc). the author would wish it.

thanks for reminding the world of this.

Musab

Ben, with the state of immigration detention and the re-introduction of racial profiling under the pretext of anti-terrorism, I think the type of institutional racism mentioned in the Mapherson report is still here and strong as ever. Actually, though, I think Carmichael and Hamilton were misunderstood by Macpherson. The institutional racism they discussed was innately connected to colonial (and neo-colonial) exploitation and is essentialy a critique of the historically racist nature of modern capitalism. To separate it from the economic system, as in the Stephen Lawrence enquiry, is to take the phrase at only a superficial understanding in my view.

Omayr

jokes, as soon as i saw the title of the article i knew you had something to do with it. good work tho man, also check this out http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=HU-PNWxhjr8 (interview with former black panther Angela Davis)

Thanks for this useful post 🙂

thank you for posted

very nice blog 😀

My name is emel 😀

Rather shamefully, I have never heard of this book prior to reading this article. However, the beauty of life is that we have the chance to learn something new everyday. I thank Musab Younis for writing this beautifully written and articulate piece, which I found both interesting and informative. Being English/Jamaican, I had the unfornate experience of receiving racism from both sides of the fence. This book, though written a long time ago, needs to be put back in print. And as the title states, I also firmly believe that we can learn from Black Power.