Review | Cruel Britannia: A Secret History of Torture Books

Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Monday, January 21, 2013 0:00 - 3 Comments

By Musab Younis

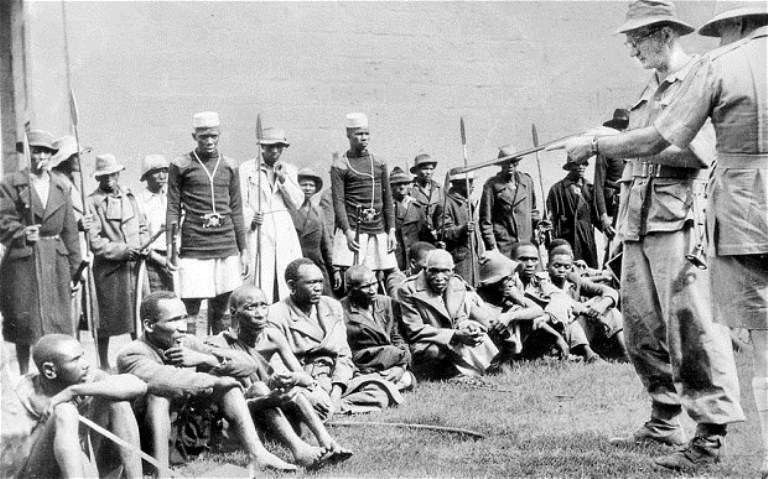

British soldiers guard Kenyan captives during the 1950s

During last year’s patriotic resurgence – the Olympics, and those Union Jacks goose stepping down Oxford Street – I was reminded of a sentence I’d read in a book of interviews with African women writers. It was part of an interview with the Ghanaian author and playwright, Ama Ata Aidoo, and it read: ‘My grandfather was imprisoned and killed by the British, so in a way I have always been interested in the destiny of our people.’

Aidoo’s use of the term ‘British’ – its matter-of-factness, its signature melody of violence – represented, to me, the ways in which a supposed national character is never simply a domestic discussion, but is also owned by the memories and experiences of many external others, who can be glimpsed skirting the shadows of ‘our’ national discourse. Ian Cobain’s Cruel Britannia, as you might guess from the title, lays in front of us a series of similar reminders. His conclusion that ‘torture can be seen to be as British as suet pudding and red pillar-boxes’ will be difficult to accept for many. It is worth considering the idea that for many others – in the unlikely event we decide to ask them – it will appear a truism.

Cruel Britannia is easily the most important work of investigative journalism produced in Britain in the last year, and one of the best insights into the functioning of Britain’s intelligence services since Seumas Milne published The Enemy Within in 1994. Cobain’s prose retains a remarkable evenness that preserves interest in his subject matter without exploiting its sordidness. And his ability to marshal such extensive documentary evidence, so soon after events, is deeply impressive.

Such evidence brings us, early in the book, to Fritz Knöchlein, a Waffen SS lieutenant colonel who was captured by the British, and who found himself after the war in a prisoner of war interrogation centre known as the “London Cage”. Knöchlein, who was accused of war crimes, later gave a detailed statement about his treatment in the Cage, in which he described being deprived of sleep for many days, fed only a meagre diet, forced to walk in a tight circle for hours while being kicked at each turn, put to work cleaning lavatories with a tiny rag for days on end, forced to stand for prolonged periods in a specially-constructed freezing shower, and made to run in circles carrying heavy logs.

‘All this was happening,’ notes Ian Cobain, ‘just a few hundred yards from Hyde Park and less than three miles from Downing Street.’ The force of this proximity, we soon realise, is more than merely suggestive: as Cobain shows, a carefully worked-out code of torture techniques has been passed down and across the British army and intelligence services for many decades (Cobain’s book starts at the Second World War; the record on earlier periods exists elsewhere for those with strong stomachs).

In Palestine, Malaya, Aden, Cyprus – then Ireland, then Iraq – these methods were tested, finessed, developed, and systematically put to the test. At Bad Nenndorf, a British interrogation centre in postwar occupied Germany, prisoners emerged barely alive, starving, with frostbite, amputations, paralysis. Some of them had actually taken their leave from German concentration camps only to end up at Bad Nenndorf, such as Hans Habermann, a 43-year-old disabled Jewish man who had survived three years in Buchenwald concentration camp (the British, not Buchenwald, left him toothless.)

This interrogation centre had initially been intended for those linked to the former Nazi party, but it quickly expanded to include communists, Russian defectors, and others viewed with suspicion. One gay man, Osterreicher, who had used forged documents in an attempt to locate his lover, was slowly starved to death. In a sentence we are unlikely to encounter in school history books, Cobain explains that the British ‘had removed a number of “shin screws” from a Gestapo prison in Hamburg and had put them to use at Bad Nenndorf.’ When the commanding officer, Lt Col Robin Stephens, was eventually court-martialled, Cobain notes that he used ‘the very defence that had been offered – unsuccessfully – by countless concentration camp commandants at war crimes trials’: that he was unaware of what had been taking place. He won his case.

Nenndorf wasn’t alone, but was part of a network of prisons operated across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. As Britain’s ‘Empire Project’ (to use John Darwin’s phrase) began to face postwar resistance, techniques were transferred, though sometimes – as in Kenya, where recent scholarship has exposed a great deal – they became yet more brutal. After visiting Aden, Britain’s then-major outpost in Yemen, Peter Benenson, founder of a nascent organisation called Amnesty International, reported ‘I never came across an uglier picture’, and resigned his presidency, warning that the British government was bugging Amnesty’s offices.

As whip marks became increasingly unsightly, ‘the British devised a method of torture that combined isolation, sensory deprivation, seemingly self-inflicted pain, exhaustion and humiliation’ which would ‘cause intense pain and terror, plus lasting psychological damage’, but without leaving external marks. This method became standardised in the form of the so-called ‘Five Techniques’: hooding, starvation, sleep deprivation, incessant white noise, and a painful stress position known as ‘wall-standing’. The package of techniques, intended to have a cumulative effect, was held together using a crucial but unspoken sixth technique – severe beating – to ensure prisoner cooperation.

The Five Techniques are discussed by Cobain at length, with detailed accounts from former prisoners and guards. They were useful in quelling various sorts of uprisings – as Cobain notes in an aside, they helped crush a miners’ strike in Swaziland – but in large part, their use coincided with large-scale British counter-insurgency in a range of rebellious colonies. A substantial section of this book discusses their application in Northern Ireland, where interrogators (‘a handful [of whom] did cooperate with me in the writing of this book’) were given wide legal latitude through a series of legal decisions, including the infamous Diplock judgement.

Here we encounter British interrogators indulging in the joint twisting technique known as ‘hyperflexing’, the forced and barefoot running over ‘obstacle courses’ strewn with broken glass, electric shocks via a needle inserted into the arm, and controlled drowning (‘waterboarding’). But more prominent than these is the unremitting use of the Five Techniques. Predictably, the British interrogators’ trousseau led to cases of forced confessions, trauma, and an upsurge in local anger and violence. ‘It is even possible that the use of the Five Techniques is one of the reasons that the cycle of violence lingers on in Northern Ireland in the twenty-first century,’ suggests Cobain.

On September 12, 2001, the only aircraft to enter American airspace was carrying senior British intelligence officials, including Eliza Manningham-Buller, the deputy head of MI5, and Sir Richard Dearlove, the head of MI6. As is now known, the plan developed by the CIA in response to 9/11, which was soon adopted by George W. Bush, was ‘a vast expansion of the rendition programme’ in which hundreds of suspects ‘would be tracked down and abducted from their homes’ and ‘systematically tormented until every one of their secrets had been delivered up.’

During the evening of September 17, 2001, Cofer Black, George Bush’s head of counterterrorism, went to the British embassy in Washington and informed senior British intelligence officers of this plan: ‘At the end of Black’s three-hour presentation, his opposite number at MI6, Mark Allen, commented drily that it all sounded “rather blood-curdling”’; ‘[a]ccording to one account, even Black joked that one day they might all be prosecuted.’ This is not secret information – though Cobain complements the existing record with his own insightful interviews – but it is nevertheless crucial. When the British government became nervous about its deep involvement in this global kidnap and torture programme it feigned ignorance, but the extent of the knowledge of key individuals is now remarkably easy to establish for any hypothetical war crimes prosecutor.

Nineteen British airports and RAF bases were used at least 210 times by the CIA’s ‘rendition’ fleet for stopovers and refuelling, as was the British territory of Diego Garcia (see crimes passim), possibly for interrogation. When a number of young British men, all Muslims, ended up in a US interrogation centre at Kandahar airport, we know the British government had the option of prosecuting them in Britain. But government lawyers warned that ‘these men appeared not to have committed any offence under UK law’ and helpfully suggested that ‘police interviews in the UK would not be so effective as interrogations conducted overseas’. Ministers decided, as a secret Foreign Office memorandum states, that their ‘preferred option’ was the rendition of British nationals to Guantánamo.

On 10 January, 2002, Jack Straw issued a classified telegram ordering that there was to be no objection to any such transfer, declaring it ‘the best way to meet our counterterrorism objectives’. (Clearly unaware these documents would emerge, Straw was proudly proclaiming, as late as 2005, Britain’s innocence of any involvement in rendition, dismissing such discussion as ‘conspiracy theories’.) Straw did ask, however, for the British detainees’ removal to be delayed long enough to permit MI5 interrogators to question them.

Four days later a six-page memo was sent to David Manning, Blair’s foreign policy advisor, by a senior Cabinet Office official, naming the British men being held in Afghanistan and noting that they were ‘possibly being tortured’. We know that Blair was made aware of this: in a handwritten note commenting on the memo, instead of demanding a stop to the torture, he added an instruction to ‘v quickly establish that it isn’t happening’.

Almost all the British citizens and residents who found themselves in Guantánamo were sent there after this little note was written, and at least one British man, Martin Mubanga, is shown by documents later disclosed in court to have been sent there after the personal intervention of ‘either Blair or someone close to him at Downing Street’. When a court discovered that MI5 and MI6 had been fully aware of the torture of a British resident, Binyam Mohamed, before they questioned him, it was David Miliband – then Foreign Secretary – who tried to redact seven paragraphs from a court judgement describing Mohamed’s treatment.

So we come to the realities of Britain’s ‘outsourced torture’, in which Mohamed, now in a Rabat dungeon, was beaten, cut with scalpels in his genitals and subjected to continuous sleep deprivation, while being interrogated with questions supplied from London, where his responses were duly delivered. The British security services denied they knew where he was. Later, evidence surfaced that one of their agents had actually visited the Moroccan torture centre on three occasions while Mohamed was being held there, after which MI5 had sent the CIA ‘a list of seventy questions that it wanted put to Mohamed.’ From there, for Mohamed, it was to a darkened cell in Kandahar, from there to Bagram, from there to Guantánamo – for four and a half years.

Cruel Britannia’s dénouement involves more familiar names (Manningham-Buller comes to the fore), as it traces the extent of recent British involvement in torture abroad, a story which might be familiar to many, but which is given particular weight in light of the devastatingly long charge sheet laid out by Cobain. MI5 became proficient at questioning British men in Pakistani custody – and, according to a senior official at Pakistan’s Intelligence Bureau, ‘breathing down our necks for information’ – in between the whippings, stave beatings and sleep deprivation administered by local interrogators.

By mid-2007, we know that David Miliband was being regularly consulted by MI6 when it was planning to ‘conduct an operation that could result in a person being tortured.’ ‘Miliband is proud of the fact that, on occasion, he said no,’ states Cobain. ‘On the other hand, according to a source with intimate knowledge of his deliberations, he often said yes.’ (These revelations appear to have had zero effect on Miliband’s promising frontbench career). Jacqui Smith and Alan Johnson, according to Cobain’s source, dealt with MI5 requests in a similar way.

The 2011 overthrow of Gaddafi has meanwhile revealed a UK-Libya rendition programme in which the British government became closely involved in the kidnap of Libyan exiles, spiriting them to Libyan torture chambers where they were given electric shocks, hung from walls, injected, and submerged in icy containers. One former prisoner remarks: ‘I wasn’t allowed a bath for three years.’ When Blair suggested he didn’t know this was happening – despite having personally met Gaddafi in 2004 to cement a ‘counterterrorism’ relationship – MI6 reacted by making clear British security service actions in relation to Libya were the result of ‘ministerially authorised government policy.’

But not all torture was outsourced: in Iraq, as we know, the British army was able to show it had not forgotten its traditions. Last month, one of the investigators into British torture in Iraq, Louise Thomas, told a court that she had left her position because it had emerged the process was a ‘cover-up’, with deliberate tampering of evidence. Her statement, though angrily refuted, was hardly a surprise. It fits a familiar pattern in which, as Cobain notes, ‘[i]nquiries into allegations of torture and murder by the British military in Iraq were conducted by military police who were often under-staffed and poorly resourced,’ and where ‘some of the investigations appeared design to carefully bury evidence rather than unearth the truth.’

But not all torture was outsourced: in Iraq, as we know, the British army was able to show it had not forgotten its traditions. Last month, one of the investigators into British torture in Iraq, Louise Thomas, told a court that she had left her position because it had emerged the process was a ‘cover-up’, with deliberate tampering of evidence. Her statement, though angrily refuted, was hardly a surprise. It fits a familiar pattern in which, as Cobain notes, ‘[i]nquiries into allegations of torture and murder by the British military in Iraq were conducted by military police who were often under-staffed and poorly resourced,’ and where ‘some of the investigations appeared design to carefully bury evidence rather than unearth the truth.’

Reading this book, one wonders with what regularity a pattern of behaviour must repeat itself before it can be declared a ‘national’ characteristic. As ever, the response is likely to depend on whom you ask.

Cruel Britannia

By Ian Cobain

Portobello, 2012

£18.99

3 Comments

Monique Buckner

Jyotiswaroop Pandey

Torture has been an operational strategy of all police agencies for extorting information,whether third degree physical torture or guilt-plea inducing psychological torture.

A Pakistani neuroscientist Dr. Aafia Siddiqui, who is serving her 86 years sentence in New York sent a message through Pakistan’s Consul General saying “I want to get out of prison, by imprisonment in the US is illegal as I was kidnapped and taken to the US”.

Aafia has been in prison since 2010 after the verdict of New York court.

My family was subjected to starvation, rape, lack of medication and shelter when they were in British concentration camps in South Africa in 1901 during the war with Britain. British soldiers bayoneted the cattle and sheep on South African farms while the houses and crops were burnt to the ground in order to deliberatly cause mass starvation and death due to exposure to the elements. Britain still to this day has never apologised for the concentration camp atrocities and the destruction of property, or admitted that ‘they didn’t know it would lead to suffering’ was a lie. They left children in the pouring rain and bitter cold and then denied them medical attention or hygiene when they got sick. The concentration camp inmates where sexually brutalised and denied food and clean water. The British claimed that they had no idea how to provide for all these people they had deliberately made homeless and dependent (yet ‘miraculously’ were able to provide for and shelter their own soldiers). The Kenyan survivors of British concentration camps are still waiting for justice. My people will never see justice through even a simple apology. If Britain really believed in the equality of humanity, it would not be so difficult to acknowledge wrongdoing and recognise suffering. But there is such blatant social apartheid in modern Britain that I can in a way see why the British do not do apologies and compensation very well. They are used to being treated unequally and see treating ‘The Other’ as sub-human perfectly normal in such a twisted system. They will never deny me my own humanity, but on a daily basis, they deny their own.