Syria: Blundering and Adapting Essay

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Saturday, May 21, 2011 0:00 - 3 Comments

‘Cancelling the State of Emergency’ – By Ali Farzat

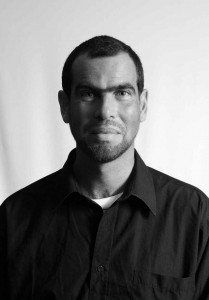

By Robin Yassin-Kassab

Like all Syrians pure or hyphenated I’ve been regarding my father’s country over the last weeks with the utmost horror. The Damascus suburb where I got married is currently sealed off by tanks, its dovecots occupied by snipers. When I lived and worked there, Syria felt like a land of promise. Did it have to come to this?

On the one hand, Hafez al-Asad, father of the present president of Syria, was a ruthless dictator who put down a violent uprising (in the 1980s) by slaughtering 20,000 people in the city of Hama. On the other, his regime brought stability after two decades of non-stop coups, provided services to urban and rural areas alike, educated a middle class to staff the public sector, and based its legitimacy, often with good reason, on a nationalist foreign policy.

The regime liberalised somewhat in the latter years of Hafez’s reign, once the Islamist opposition had been neutralised. Syria remained a dictatorship, dissidents were still jailed, but it was no longer a country of fear. When Bashaar took over from his father eleven years ago Syrians hoped for accelerated reform within continued stability. And the regime did make a good start at liberalising the economy, but reneged on early promises of political reform. The model was China, not Gorbachev’s Russia, but growth levels were never Chinese. The result was the enrichment of a new bourgeoisie simultaneous with the undercutting of safety nets for the poor majority.

Over the last eight weeks the regime has made one blunder after another. If Bashaar had shown the political adaptability his father applied in geo-strategy, and if he were the pan-Arabist he claims to be, he might have realised when the revolution reached Egypt that the Arabs were undergoing an inevitable process of change. He might have exploited his undoubted popularity to facilitate the change, and he might have entered history as a great Syrian statesman. Instead he told an interviewer that Syrians would be ready for freedom in another generation, and once protests and killings started, gave a silly giggling performance before the rubber-stamp parliament, and pretended to reform even as his security forces shot the innocent.

The regime has external enemies ranging from Israel and Saudi Arabia to neo-con expat Syrians, but the motor of the uprising is internal, based on specific grievances, and has to a large extent been powered by the regime’s own miscalculations. By arresting schoolchildren, the regime caused protests in Dara’a. By killing protestors, the regime caused protests all over the country. Those who first called for reform now call for the fall of the regime.

Yet regime propaganda trots out the same silly stories told by Ben Ali, Mubarak and Gaddafi: that the rights movement is run by Salafis, al-Qa’ida-types, foreign infiltrators. (One ‘Salafi’ confessed on state TV to violent insurrection. It so happens that this man is a friend of a friend. Apparently he isn’t even religious, let alone a Salafi terrorist. His seven-year-old son was arrested with him, and has not been seen since; surely this has something to do with the man’s televised ‘confession’.)

A good number of Syrians want to believe the regime’s version of events because they are genuinely fearful of the chaos regime-change could unleash. Others are guilty of class and sectarian prejudices, and ascribe only the worst intentions to the ‘mob’. Others still suffer what must be called a slave mentality. They have grown so used to justifying the government’s violence against them that they now believe it has a perfect right to murder men, women and children, as many as it sees fit.

Most Syrians, however, have had their illusions shattered. Their president kills to keep his seat. It only makes it worse that he once pretended to be something different. The nationalist pretensions also ring hollow after the president’s cousin told the New York Times, “If there is no stability here, there’s no way there will be stability in Israel.” Syrians had previously been told that their half-century State of Emergency was designed to confront Israel – which occupies the Syrian Golan Heights – not to protect it.

The regime has responded to protests by evoking sectarian demons. Just as the Sunni-minority Bahraini regime paints the democratic uprising there as a Shia plot, the Syrian regime characterises its opponents as Sunni fundamentalists, hoping to terrify secularists and religious minorities into obedience. (The president is a member of the Alawi sect, and many Alawis fear the kind of generalised revenge suffered by Sunnis in post-Saddam Iraq). While warning against sectarianism, the regime is arming Alawi villages around restive Sunni towns.

The other tool in the regime’s armoury is extreme violence. About a thousand Syrians have been killed so far, and about ten thousand have been detained – which means being beaten, starved, sometimes electrocuted.

But the protestors are adapting. Demonstrations now tend to be smaller but scattered in various locations, some lasting for only a few minutes, some held at night. The new tactics aim for sustainability of protest in a political war of attrition – to give soldiers more time to be shamed by their families, and figures of authority more time to question their loyalties, as well as to exhaust the security forces. Protests occur in the big two cities and all over the provinces. The uprising is in fact deepening. Last Friday, very significantly, protests reached privileged areas of Homs and Damascus.

It would be wrong, however, to suggest that the uprising is scenting victory. Despite reports of loyalist and rebellious soldiers clashing in Dara’a, the security forces (as opposed to the army) have remained fiercely loyal to the regime. And the protests are not attaining the critical mass they reached in Egypt. A call for a general strike last Wednesday went largely unheeded. It’s very unlikely that Syria’s ‘silent majority’ still supports the regime, but it is certainly too scared, for now at least, to openly defy it.

A Syrian friend describes the country today by the metaphor of bait at-ta’a, or ‘house of obedience’, the archaic custom in which legal pressure would force a woman fled from an abusive husband to return to the marital home. Bashaar is the bullying husband, the security forces the court, and the people the coerced wife.

A ‘restabilised’ Syria will not be stable. The economy is reeling from capital flight, the collapse of tourism and foreign investment. Syria’s isolation from Europe and, particularly, Turkey – which has spoken forcefully against its former ally – will further exacerbate the crisis. Many Syrians are already buying weapons as insurance against the future. If resistance to state violence gives birth to militias, regime propaganda will become reality and the ensuing sectarian mayhem will undoubtedly spill into Lebanon.

There was less killing last Friday, and the regime’s vocabulary has turned again towards ‘dialogue’. Syria’s best hope is the immediate cessation of state terror and a staged transitional process. Its worst fear is that the regime will choose to pull the country down with it as it goes.

This is an extended version of an essay published at www.pulsemedia.com

Robin Yassin-Kassab is the author of The Road From Damascus, a novel published by Penguin. He co-edits www.pulsemedia.org and blogs at www.qunfuz.com

Robin Yassin-Kassab is the author of The Road From Damascus, a novel published by Penguin. He co-edits www.pulsemedia.org and blogs at www.qunfuz.com

3 Comments

Omer

Enrique

Great essay!! Do you think that a covert action against the Bashar al-Assad’s government is appropriate?

v/r

Rick

Books | Review | ‘Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War’ – AllMagNews

[…] See also: Robin Yassin-Kassab: Syria: Blundering and Adapting […]

Excellent piece. However, I take issue with the following: “Syria remained a dictatorship, dissidents were still jailed, but it was no longer a country of fear.” I contend that it was.