Here to Stay, Here to Fight: On the history, and legacy, of ‘Race Today’ Books

Arts & Culture, Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, October 31, 2019 18:17 - 0 Comments

By Leila Hassan, Robin Bunce and Paul Field

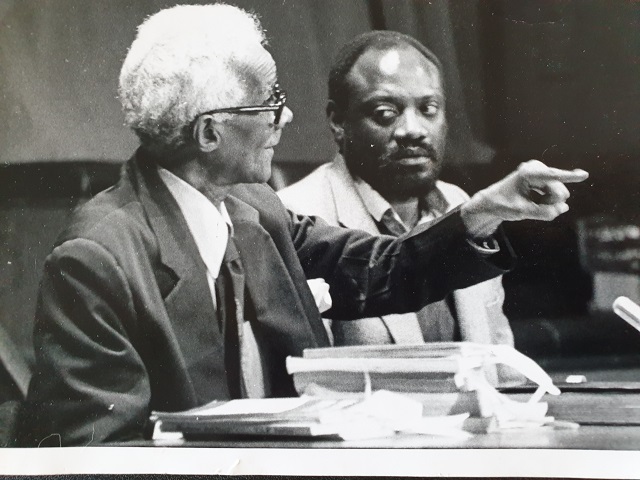

CLR James and Darcus Howe at CLR James’s 80th Birthday Lectures, Kingsway Princeton College, Camden, 1981.

From 1974 to 1988, Race Today, the journal of the Race Today Collective, was at the epicentre of the struggle for racial justice in Britain. Race Today was groundbreaking in terms of its reports and analysis of struggles by Black and Asian workers in the UK against police and state racism. These insights flowed from the work of the Race Today Collective, work which was not merely journalistic. For the Collective was a campaigning organisation, which supported grassroots movements, movements which sought to advance the struggle for Black Power, the fight for women’s liberation, and the anti-colonial campaign to free the ‘Third World’.

Race Today placed race, sex and social class at the core of its analysis of events in Britain, and across the world. Its writers reflected the magazine’s global reach, as the magazine included contributors such as C.L.R. James, who lived above the journal’s offices in Railton Road, Brixton; Darcus Howe and Leila Hassan, the magazine’s editors; and writers, activists and intellectuals such as Mala Sen, Barbara Beese, Akua Rugg, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Selma James, Farrukh Dhondy, John La Rose, Martin Glaberman, Walter Rodney, Maurice Bishop, Bukkha Rennie and Franklyn Harvey.

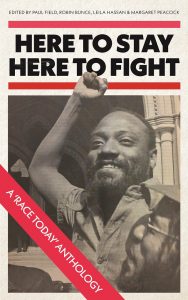

While Race Today was widely read and influential in the 1970s and ’80s, the magazine is now hard to access, as only a handful of archives contain the complete run. As such, the Race Today anthology, Here to Stay, Here to Fight, published this fall by Pluto Press, aims to bring the insightful journalism and fearless activism of the Race Today Collective to the attention of a new generation, at a time when the struggle for racial justice has never been more urgent.

With the struggle against police brutality and racism gaining new impetus through the Black Lives Matter movement, with the Far Right on the march again in the UK, US and Europe, there is an appetite among younger activists to learn about the recent history of Black radicalism in Britain, a history which Race Today chronicled, and in which the Collective played an essential part.

From its inception, the Race Today Collective lent its organisational weight to dozens of grassroots justice campaigns, including those to free the Brockwell Park Three, the Bradford Twelve, and George Lindo. The biggest test of the Collective’s strength occurred in 1981. In the wake of the New Cross fire, they conceived and organised the Black Peoples Day of Action, a mass protest which saw 20,000 people, the vast majority Black, march through London, chanting ‘Thirteen Dead and Nothing Said’.

Similarly, the Collective and its journal were instrumental in helping to organise the largest squat in British history in London’s East End. Through their work with the Bengali Housing Action Group (BHAG), the Collective achieved the seemingly impossible: An entire community was re-housed by the GLC following a 3-year campaign of direct action in which dozens of Bengali families squatted vacant properties.

Turning to the rights of workers, the journal published eyewitness accounts and analyses of the Imperial Typewriters and Grunwick strikes by Asian workers against sweatshop employers. The Collective also covered the insurrections led by Black youth at Carnival in 1976, and the uprisings which began in Brixton in April 1981 before spreading to sixty other cities. When Black youth rose up again in Brixton and Broadwater Farm in 1985, Race Today provided a voice for the dispossessed.

Race Today saw culture and politics as inseparable. Writers such as Howe, Johnson, Dhondy and Rugg argued that liberation movements and cultural movements emerged hand-in-hand. From this perspective, the magazine sought to provide a platform for self-expression of Black people, women, workers and others oppressed by capitalism and imperialism. Through its cultural arms – Creation for Liberation and the International Book Fair of Radical and Third World Books – and through their participation in a mass band at Notting Hill Carnival, Race Today and its sister publication Race Today Review brought the work of Black artists such as Toni Morrison, Grace Nichols, Mickey Smith, Lorna Goodison, Ntozake Shange and Jean ‘Binta’ Breeze to public attention.

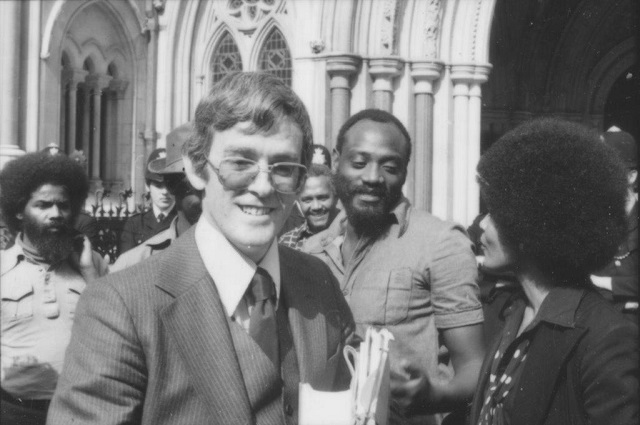

Darcus at Clifton Rise during the anti-National Front demonstration, 13 August 1977 (photo Syd Shelton)

Origins

As Linton Kwesi Johnson notes in the anthology, it was Howe’s appointment as editor, on 6 November 1973, which set Race Today, formerly the liberal monthly publication of Chatham House’s Institute of Race Relations, on a radical new course. A well-known Black Power activist, and one of the Mangrove Nine, Howe was a controversial choice. Howe’s selection was a consequence of the revolution in the Institute’s political outlook. His appointment was made possible after the Institute’s staff under the leader-ship of A. Sivanandan, its former librarian, succeeded in wresting control from its paternalistic Council and transformed it into an anti-racist organisation.

The Guardian noted that Howe’s editorship ‘promises to steer the magazine yet further from its academic origins towards the front line of racial politics’[1]. In August 1974, this wish to place Race Today on the front line of the emerging struggle for racial justice, led Howe to break with the Institute completely. Assisted by Olive Morris, the core of what would become the Race Today Collective relocated the magazine to a squat at the heart of Britain’s Black community in Brixton, South London.

Freed from all constraints, Race Today became the journal of a ‘small organisation’. The Race Today Collective was established in 1974 along explicitly Jamesian lines. Taking inspiration from James et al.’s Facing Reality (1958), the new Collective recognised that as a truly revolutionary socialist group, it was not their role to act as a self-appointed vanguard to the working class. Rather, the Collective sought to establish a paper (and small publishing house) which, like the ‘paper of the Marxist organization’ described by James, would ‘recognize and record’ the struggles of the working class.[2]

Writing in Race Today, Howe argued that a paper ‘can only do this by plunging into the great mass of the people and meeting the new society that is there.’ Howe described this task in his first editorial in recognisably Jamesian terms:

“Our task is to record and recognise the struggles of the emerging forces as manifestations of the revolutionary potential of the black population. We recognise too the release of intellectual energy from within the black community, which always comes to the fore when the masses of the oppressed by their actions create a new social reality”. (January 1974).

Outside Royal Courts of Justice, September 1977, following Darcus’s successful appeal and release from prison. Selwyn Baptiste, Darcus Howe, Ian Macdonald, John La Rose, Barbara Beese.

Facing Reality

Race Today reflected a Jamesian approach to writing. Its articles foregrounded the authentic voices of protagonists, reflecting on and recording their own struggles. Martin Glaberman, one of James’s American comrades, noted that James liked to remind people of Trotsky’s criticism of the US Socialist Workers Party newspaper. The paper was produced as a means of advancing the Party line, and therefore

“Each of them [the paper’s journalists] speaks for the workers (and speaks very well) but nobody will hear the workers. In spite of its literary brilliance, to a certain degree the paper becomes a victim of journalistic routine. You do not hear at all how the workers live, fight, clash with the police or drink whiskey”.[3]

Jamesians, by contrast, went out of their way to ensure that the voice of working people appeared in their own newspaper, Correspondence. Raya Dunayevskaya, another of James’s comrades, coined the phrase ‘full fountain pen’ to describe the process of interviewing workers, typing up their words and then taking back the transcript to them to correct and verify before publication. It was this intimate relationship with, and involvement in working-class struggles and communities, which enabled Correspondence to discuss issues such as popular culture, music, cinema, sports and family life a decade before the New Left embraced such topics (Worcester, 1998).[4]

In a similar vein, the Race Today Collective gave expression to the Black cultural explosion which occurred in the 1970s and ’80s through a myriad of cultural media: Linton Kwesi Johnson via his dub poetry and music; Farrukh Dhondy through his novels and plays; C.L.R. James through his sports writing, literature and literary criticism; Jean Binta Breeze and Mikey Smith in their spoken poems. The Collective even formed their own masquerade band known as ‘Race Today Mangrove Renegade Band’ with the support of mas players from Ladbroke Grove. (They went on to win Best Costume in 1977, 1978 and 1979 at the Notting Hill Carnival). In 1977, the Race Today masquerade band celebrated insurgent national liberation movements in Africa with a mass entitled ‘Forces of Victory’. ‘Viva Zapata’, their 1978 mass, was a homage to the life of Emiliano Zapata, the Mexican revolutionary. Their 1979 ‘Feast of Barbarian’ was rooted in Britain’s own ancient tradition of resistance to foreign rule.

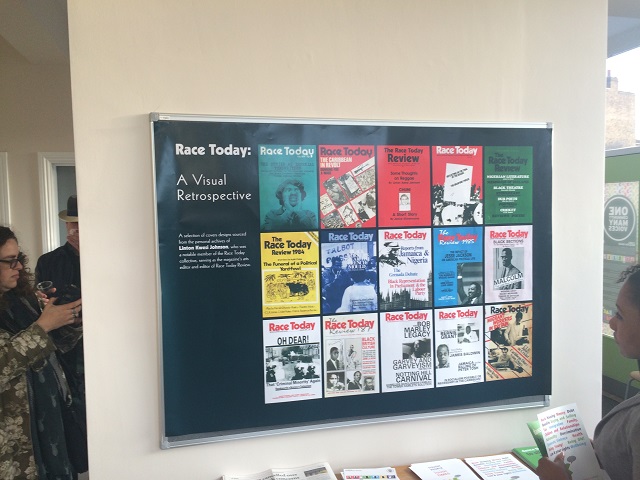

‘Race Today: A Visual Retrospective’ part of the ‘Icons of Railton Road’ art installation created by Brixton, Jon Daniels, and unveiled in October 2015 at Brixton Advice Centre in Railton Road.

Race Today’s coverage was always internationalist. It reflected the Collective’s role as part of a global revolutionary movement, which linked Black Power in Europe and the US with national liberation movements in what was called ‘the Third World’. True to James’s revolutionary socialist politics, the journal rejected ethnic nationalism. Rather, the Collective argued that the militant struggles of the Black working class, youth, and women against the state and employers had the potential to inspire the wider working-class movement to fight for power. Consistent with this rejection of ethnic nationalism was the fact that Race Today embraced political blackness, which sought to unite all people of colour who had been exploited by colonialism, and oppressed by racism and capitalism.

This was not unique to Race Today, for political blackness was a response to the experience of British imperialism. Consequently, ‘blackness as a unifying political identity’ (Wild, 2008)[5] was a feature of the wider Black Power movement in Britain, which successfully united South Asian, West Indian, and African migrants. Indeed, this concept of blackness was commonplace among Black and Asian radicals in Britain in the 1970s and ’80s, even those who worked within mainstream organisations such as the Labour Party.

Yet Race Today remains, perhaps, one of the best examples of this inclusive political blackness. It united Black and Asian activists in diverse struggles, united against racist violence, united in campaigns for decent housing, better schooling and for defence of the Notting Hill Carnival. Indeed, it is worth noting that consensus around political blackness collapsed soon after Race Today’s last issue.

Race Today’s commitment ‘to record and recognise’ the struggle of the Black and Asian working class was set out in Howe’s editorial of April 1974. Howe cited Karl Marx’s A Worker’s Inquiry (1880)[6] which set down a hundred questions to be asked of every worker as they ‘alone can describe with full knowledge the misfortunes that they suffer’, and provide ‘an exact and positive knowledge of the conditions in which the working class – the class to whom the future belongs – lives and moves’. The April 1974 issue of Race Today contained multiple first-hand accounts of the working conditions and struggles of Asian workers in order to provide ‘an exact and positive knowledge’ about ‘this section of the working class … involved in successive strike actions in the past five years which now threaten to develop into a cohesive and powerful mass movement of Asian workers’ (Howe, 1974).

Likewise, Race Today’s interviews with Black nurses and women health workers in August 1974, following the first-ever strike by nurses in the UK, broke new ground by identifying how gender, race and class intersected in the increased exploitation of, and discrimination against, Black nurses. Similarly, Race Today’s vivid account of the dramatic wildcat strikes at Ford’s in Dagenham, was largely based on one of the assembly-line workers’ diaries, and its description of the 1981 insurrection was in large part derived from verbatim accounts: the Race Today office, in Railton Road, Brixton, was on the front line of the uprising, and the Collective monitored the battle, recorded events and, after the insurrection was over, debriefed its leading participants.

‘Race Today: A Visual Retrospective’ part of the ‘Icons of Railton Road’ art installation created by Brixton, Jon Daniels, and unveiled in October 2015 at Brixton Advice Centre in Railton Road.

The Life of the Collective

The Collective was originally based at 74 Shakespeare Road. As the magazine’s influence grew, so did its premises. In 1980, the members of the Collective broke through a wall connecting their house on Shakespeare Road with a house on Railton Road, in order to establish a second squat. The new squat, 165 Railton Road, later became the offices of Race Today. During the 1980s, the ground floor of the Railton Road squat housed Race Today’s production team, the first floor comprised editorial offices, and James lived on the top floor.

The basement was the venue for Race Today’s ‘Basement Sessions’, which facilitated self-education. Sometimes these sessions were reading groups. Indeed, an early set of sessions was devoted to James’s Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution (1977). On other occasions, the Basement Sessions were used to build bridges with other communities involved in their own acts of resistance. In 1984, to take one example, at Hassan’s instigation, the Collective paid for the wives of striking coal miners to come to London and tell their stories.

Race Today’s final issue was published in 1988, but the Collective endured into the early 1990s. Howe was keen, at least initially, to keep the organisation going. In a letter to the members of the Collective, written in 1989, he argued that the organisation should continue as a basis for future interventions in British national life.[7] However, as Johnson recalls, James’s death in 1989 ‘created a pall over everything. Some members were affected by it. I certainly was.’ James’s death, coupled with Howe’s increasing involvement in television journalism, and his conviction that Race Today had ‘exhausted the moment’ brought the Collective to an end. The Race Today Collective was formally dissolved on 7 April 1991.

Here to Fight, Here to Stay contains some of the articles, speeches, interviews, prose and poetry published by the Race Today Collective. Much of the material comes from the pages of the 140 issues of Race Today published from 1974 to 1988, and the Race Today Review, which appeared annually from 1981. There are also references to the pamphlets put out by the Collective, which expanded on the material contained in the magazine. The book is divided into sections reflecting the breadth of the journal’s coverage and political campaigns. Each section contains an introduction from a different writer setting the pieces that follow in a broader political context, and there is a concluding section assessing the legacies of Race Today in 2019.

Here to Fight, Here to Stay contains some of the articles, speeches, interviews, prose and poetry published by the Race Today Collective. Much of the material comes from the pages of the 140 issues of Race Today published from 1974 to 1988, and the Race Today Review, which appeared annually from 1981. There are also references to the pamphlets put out by the Collective, which expanded on the material contained in the magazine. The book is divided into sections reflecting the breadth of the journal’s coverage and political campaigns. Each section contains an introduction from a different writer setting the pieces that follow in a broader political context, and there is a concluding section assessing the legacies of Race Today in 2019.

The Race Today anthology is the product of a group which includes some of the surviving members of the Race Today Collective, including Leila Hassan – editor of the journal for much of the 1980s, members of Darcus Howe’s family, Howe’s biographers, and Howe’s former comrades and colleagues. It forms part of a series of initiatives designed to ensure that the legacy and political work of Howe and the Race Today Collective are preserved for the benefit of future generations.

This essay is an edited version of the introduction to ‘Here to Stay, Here to Fight: A Race Today Anthology’, edited by Paul Field, Robin Bunce, Leila Hassan and Margaret Peacock, and published by Pluto Press in September 2019.

The Race Today Collective, May 2019. From Left to Right: Farrukh Dhondy, Michael Cadette, Jean Ambrose, Claudius Hillman, Pat Dick and Leila Hassan.

Leave a Reply