Special Report – N. Korea: The kid who would be king

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Thursday, October 7, 2010 4:25 - 2 Comments

By Peter Ward

By Peter Ward

The succession process underway in North Korea did not shock me until the face of Kim Jong un (the successor to the Kim throne) appeared in a picture. I know this probably sounds strange to you, why wouldn’t he be shown in a picture? At the time, when a professor of mine casually mentioned that fact during a conversation, I immediately broke off and started running to a computer (apologising on route for my rudeness). I was in shock. Yet I was far from being the only one; many North Korean refugees, here in the South were also shocked.

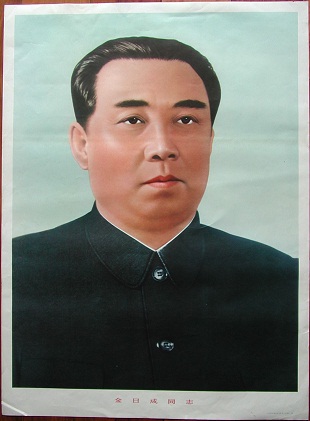

Kim Il Sung was 33 years old when he addressed a crowd in Pyongyang upon his arrival in the city in 1945. He would take full control as head of state in 1948 (declaring the North Korean state in the process). At 36 years old, he was very young by Korean standards for a non-hereditary monarch. Kim Jong Il began his rise from son to successor in 1964 at the age of 23 but would not be declared (in secret) the successor until the early 1970s. By that stage, he was in his in his early 30s but would not ‘come out of the leadership closet’ until he was 39 (the 6th Party Congress of 1980 was the event).

The process did not end there, it took a further seven years for him to take over day-to-day running of the state, and he only became head of the military in 1991. His father would die in 1994 but the process of fully installing the new leader was constitutionally completed until 1997. That process was well managed; there were a great number of purges between 1964 and 1997 which, in part, seemed to have been designed to make Kim’s ascension smooth. Kim Jong Il would rise up through the party apparatus, himself participating in purges and the ‘famed’/infamous ‘Three Revolutions Campaign’ (a Stalinist mobilisation campaign with a Maoist veneer). Throughout the 1970s, many great deeds were attributed to the mysterious ‘Party Centre’, it subsequently emerged that this man was Kim Jong Il.

The process did not end there, it took a further seven years for him to take over day-to-day running of the state, and he only became head of the military in 1991. His father would die in 1994 but the process of fully installing the new leader was constitutionally completed until 1997. That process was well managed; there were a great number of purges between 1964 and 1997 which, in part, seemed to have been designed to make Kim’s ascension smooth. Kim Jong Il would rise up through the party apparatus, himself participating in purges and the ‘famed’/infamous ‘Three Revolutions Campaign’ (a Stalinist mobilisation campaign with a Maoist veneer). Throughout the 1970s, many great deeds were attributed to the mysterious ‘Party Centre’, it subsequently emerged that this man was Kim Jong Il.

It appears that the purges that were undertaken during that succession process were not just standard Stalinist paranoia or an attempt to create loyalty through fear. According to defectors there was real and active opposition to the succession. For instance, in the form of Kim Il Sung’s brother and his cronies. Either way, the North Korean party state was progressively purged over the course of 30 years to make it completely subordinate to the emerging Sun-King himself.

Which leads us to Kim Jong Un, the third and youngest (confirmed) son of the ‘General’ (In North Korea, ever since the start of ‘Songun’ or ‘Military First’ politics, Kim Jong Il has been called the ‘General’ or Chang’un in Korean, and not the ‘Dear Leader’, as commonly circulated in the West). The young successor-to-be has the amply girth of his father and, were he thinner, he might have had the dapperness of his Grandfather. Nonetheless, he is younger at 27 then his grandfather was at first unveiling. There is another crucial difference; Kim Il Sung’s name was known widely in Korea before he mounted the rostrum for the first time in 1945. He was an anti-Japanese partisan, who fought with other militants in North-East China against the Japanese colonial administration in China and Korea. By any measure, he would be considered a national hero (if not for his subsequent deeds). He would build up a state that is often described as totalitarian (although the term is, of course, highly problematic, North Korea under him was as close as it gets to it,) and yet one in which the succession from father to son took a great deal of effort.

Kim Jong Un appears to have been playing a behind-the-scenes role in the regime for some time now, so far as rumour has it. He has apparently been credited with the sinking of the Cheonan, and other ‘great’ things related to the implementation of Computer Numerical Control (CNC) in North Korean factories. To elaborate a bit on the latter: this is a major and rather comical campaign currently underway in North Korea, the aforementioned CNC is a mechanism through which machine tools are programmed to produce highly complex products at a speed your hands couldn’t. This technology is not new. In fact, it became big in the 1960s and is now a standard of industry across the world. But in North Korea, it is deemed worthy of being part of the emerging personality cult of Kim Jong Un.

Nonetheless, Jong Un will inherit a country that would be a shadow of its form Stalinist self. The country has been crumbling since the late-1980s. Indeed, by the mid-1980s, the country’s economy had long outlived Stalinist planning and was completely stagnant. By the early 1990s, the regime was resorting to scare tactics against its own elite, demanding the population defend Socialism from ‘The yellow winds of Capitalism’. Famine struck in 1995 and things would never be the same again; Kim Jong Il moved the centre of constitutional power from the party to the army under the banner of Songun politics (“Military-First” politics). This represented a pulling up of the state drawbridge, leaving the building of a Communist utopia by the wayside in favour of nationalism and militarism. Meanwhile, the people were left in the main to fend for themselves or die. Around a million did and those who didn’t either left the state behind as a source of sustenance (in favour of markets,) or perished, through the lack of of.

If Kim Jong Il dies tomorrow, then his son inherits a state that looks like a poor African dictatorship. But there are, of course, a few very crucial differences. North Korea is in the most economically dynamic and one of the richest regions in the world. Its people live in a pitiful state but they are beginning to realise just how incompetent and brutal their country’s leadership is compared to their Southern ‘brothers’ and even compared to their Chinese neighbours.

Kim Jong Un, as already stated, is 27. He is of course too young to lead any modern state, but North Korea is different, he will be the inheritor of the most strident and shrill personality cult. He will inherit the fourth largest army in the world, and in addition he seems to have the backing of the world’s other superpower. China seems to see him as the least worst option, and if they do not back him (so the script goes) the alternative is state collapse and a massive exodus of refugees across its own borders, and even a possible war which would most likely destabilise the region and threaten China’s own fragile social ‘harmony’.

So: will it work? Even two years ago, the new contender was not seriously in our minds as a successor. Kim Jong Il’s apparent health problems from 2008 seem to have compelled the father to name a successor. Why he didn’t do so sooner is rather mysterious in itself, considering how well thought-out his own succession was.

But it appears likely that the ‘process’ will succeed, for the most part because the people who surround Kim Jong Il have no alternative locus of political support, or even an internal candidate to unite around. Moreover, if they do not unite around Kim Jong Un then there is a very high chance the state itself will splinter and result in collapse and/or civil war. There seems to have been some long overdue purges of factional rivals in the North Korean elite of late, designed to bolster internal elite cohesion around certain favoured members who would then protect and guide the newly promoted 4-Star General Heir-Apparent.

But it appears likely that the ‘process’ will succeed, for the most part because the people who surround Kim Jong Il have no alternative locus of political support, or even an internal candidate to unite around. Moreover, if they do not unite around Kim Jong Un then there is a very high chance the state itself will splinter and result in collapse and/or civil war. There seems to have been some long overdue purges of factional rivals in the North Korean elite of late, designed to bolster internal elite cohesion around certain favoured members who would then protect and guide the newly promoted 4-Star General Heir-Apparent.

Will the North Korean people wear it? There are two views on this: One says they have endured much and will continue to do so as the state itself continues to maintain its surveillance system and makes appeals to racial nationalism. The other school says the state is being withered under the pain of sanctions and the fall-outs of recent mistakes such as the failed revaluation of the North Korean Won. The corollary of the first is that, whether through terror or reform, the state can sustain itself quasi-indefinitely. The corollary of the second school is that Kim Jong Un could end up like Ceausescu toppled by his own men as his people revolt.

My own view is that, unlike Romania, North Korea has not lost its raison d’être. Romania was surrounded by a sea of post-Socialist states in 1989 that threatened the regime. Moreover, it had lost its great patron in the form of the Soviet Union. And, most importantly, its people were well aware of these facts through foreign radio and through the substantial Hungarian minority in the country (who could communicate with their newly liberated siblings across the border). North Korea still has its great enemy. The United States remains alive in the region. Concordantly it is still relatively shielded from direct influence from South Korea (because of the heavily militarised South-North border).

But most of all, the outside world has a genuine interest in its survival. Neither China nor the United States and least of all South Korea want unification or, indeed, to have to take responsibility of the seemingly colossal post-collapse mess that awaits. Romania was a single territorial and national unit whose political transition threatened no-one except its own leaders. North Korea is not, South Korea will be seen as the natural running place for North Koreans after unification and the great powers are only too aware of this.

Thus it appears that Kim Jong Un’s succession, whilst scoffed at by us, all will be tacitly supported by our governments in the interests of real politik. The regime itself will probably come under Chinese dominion before very soon; this will not be popular with anyone (least of all the Chinese and North Korean peoples themselves), but it appears to be the only way to lift North Korea from its current state.

This is the view of Aiden Foster-Carter, a famed expert on the Korean peninsula. But on one point I disagree with him, if China seriously starts to take control in North Korea, as he expects, the same problems will resurface. The North Korean people and military will not fear orders from a Chinese-backed North Korean state apparatus in the same way they fear their own ‘General Kim Jong Il’.

And yet, I think it would be best to add a different slant to this situation. To come back to the post-soviet analogy, this time considering the case of East-Germany, things are not so clear. Indeed, the more I think about this situation, the more unsure I feel, not least because North Korea is very unlike East-Germany in several respects. The German Communist government lifted its ban on watching West German TV stations in the early 1970s, East Germans, unlike North Koreans, were well aware of the lives that their brothers lived. There are many theories as to why the Eastern Bloc countries collapsed whilst their Asian fraternal Socialist brothers did not.

It seems to me that the proximity to Western Europe and the long-term memories of alternative systems, as well, as the economic stagnation and decline of the Eastern bloc in the 1970s and 1980s made a potent cocktail. This cocktail was absent from North Korea (and China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos too for that matter). Moreover, it must be remembered that the differences between North and South are far bigger in social and cultural terms as a result of the information blackout and the relative prosperity of East Germany contra West Germany.

Moreover, until very recently it seemed that most NK residents would still rather not leave even, when they did find out of how poor they were. As a very shrewd observer of North Korea, Brian Myers, points out, North Korean refugees are in the main those who felt they had no option but to leave. Specifically, they would starve, be shot or imprisoned had they stayed. This is borne out by the refugee population in South Korea and China. They are, in the main, either fugitives or political defectors, or formerly starving/ penniless peasants.

The middle class in the main have not defected and remain unwilling to, even those working in markets where rumours of the riches in China and South Korea are legion, and despite the widely-available, widely-seen contraband videos giving a strong impression of just how rich the outside world is.

Here are two examples of this: in the 1980s when South Korea was under a corrupt and rather brutal (but positively cuddly by North Korean standards) military dictatorship, the North Korean state media would show images of South Korean protests. These images were designed to reinforce state claims of the superiority of the Socialist system and the corruption, poverty and misery that was supposedly endemic in South Korea. Yet these images had the opposite effect, North Koreans began to notice the relative prosperity of their South Korean brothers from these images.

Here are two examples of this: in the 1980s when South Korea was under a corrupt and rather brutal (but positively cuddly by North Korean standards) military dictatorship, the North Korean state media would show images of South Korean protests. These images were designed to reinforce state claims of the superiority of the Socialist system and the corruption, poverty and misery that was supposedly endemic in South Korea. Yet these images had the opposite effect, North Koreans began to notice the relative prosperity of their South Korean brothers from these images.

Today one of the side effects of the swap from analogue to digital is that Chinese people have jettisoned their old VHS machines and video cassette tapes. A great many of these have ended up in North Korea. Many North Koreans watch these videos today, yet this does not inspire many defections. Nor does the spread of South Korean culture necessarily encourage defections; on the contrary it might just as well discourage them.

The very unique and, to us of course, horrifying society that North Korea is, socialises its people in such a way that living outside it could obviously be very difficult indeed. So much so, that there have been several recorded cases of double defections, people who have escaped to the South as refugees (via China and/or a third country) and then returned to the North. It is possible that if North Koreans became well informed of their own plight and have a method of easy escape without the threat of harsh sanctions, they would nonetheless in the main stay put if the Chinese and/or South Koreans began to pump in investment, construct infrastructure and guarantee work in the medium term for most (until the Northern economy starts to grow).

This is the view of a very good English Language Professor in Seoul. Furthermore if this is the case, they may also not overthrow their government, the Jong Eun succession might remain stable even if the country gradually starts to reform under his tenure. So long as the regime doesn’t appear to stop believing and articulating the same old blend of militant, ethno-nationalism and socialism, and concurrently maintains its terror apparatus then North Korea, as we know it, may be with us for decades to come.

Peter Ward, Ceasefire‘s Korea correspondent, is a writer and researcher based in Seoul. His interests include philosophy, history and politics. His blog ‘Confessions of Stranger’ can be read here.

2 Comments

Brady

Ceasefire Magazine – This week in Ceasefire

[…] N. Korea: The kid who would be king […]

Provoking insight and quite different from what is heard on the nightly news.

It seems what you are saying is that the most likely scenario is a continuation of the North Korean state in one form or another, simply because it would be impractical for it to collapse. No one wants to take on the monumental task of ‘fixing’ North Korea, though I’m sure many a businessman cast hungry eyes to the North every so often.

The question is with this quick transfer of power, does Jong Un have the attitude, support, or skills needed to rule at near the same level of his predecessors? The leader of North Korea must have certain characteristics that a dictator in Africa wouldn’t necessarily have to possess…if he really ends up being nothing more than a puppet propped up by China or some of the NK Old Guard, then…nothing happens? It would seem like there is a danger of the regime losing more control, and making even more desperate actions to retain their sovereignty.

In contrast to this idea of an essentially reclusive and introverted country, there is a lot of emphasis put onto North Korea’s weapons programs. According to the Independent.co.uk, Kim Tae-hyo, President Lee Myung-bak’s deputy national security adviser, “The threat posed by North Korea’s nuclear programme has reached an “extremely dangerous level”…” Other articles point towards continued weapons development, and as you mentioned here, the World’s fourth largest standing army (And probably First Hungriest).

However, most of this is likely rhetoric and posturing. As you noted in your comparisons, North Korea is in some ways a unique snowflake among its totalitarian siblings. It is squeezed between competing powers who only half-want anything to do with it. With no one wanting to foot the bill for the reconstruction, left in limbo bouncing between world powers, eventually something will give way without a strong leader.