Senegal: Democracy on the brink Special Report

New in Ceasefire, Politics - Posted on Saturday, February 25, 2012 12:00 - 0 Comments

“Against violation of the Constitution, stand up”. Dakar, December 2011 protests (Photo: Oualid Khelifi)

Tomorrow, Senegal faces another crucial test to safeguard its democracy. The incumbent president, Abdoulaye Wade, insists on running for a third time after a controversial constitutional amendment was passed last month that allowed him to do so; and which has provoked widespread protests lasting for several weeks. At least ten protesters were killed in clashes with security forces and hundreds injured and hospitalised. With the elections scheduled tomorrow, 26 February, most Senegalese fear that the peace and democracy they have been building and consolidating since independence could be swept in a burst of political violence.

Senegal has long been hailed as West Africa’s model for democracy and political stability. Since independence from France in 1960, it has remained the only country in the sub-region which had not endured a military-coup, a fact which both the leadership and the population at large constantly and deservedly celebrate. Indeed, when compared to neighbouring countries in the vicinity, Senegal has thus far avoided major bloodshed or civil wars.

However it would be rather inaccurate and misleading to state that the republic was spared all forms of political violence. Throughout its post-independence history, Senegal has regularly experience waves of riots, suffered periods of civil unrest, been a theatre to several political assassinations, not to mention the 30 year-old armed conflict between Dakar and rebels seeking self-determination in the southern region of Casamance.

But this year’s presidential elections are taking place in an unprecedented, and rather volatile, context. Tomorrow, 26 February 2012, the incumbent president, Abdoulaye Wade, is planning to secure his third mandate to add to his 12 years of rule so far. The highly controversial constitutional amendment adopted in late January this year could harm the very foundations of Senegalese democracy and plunge the country into the unknown.

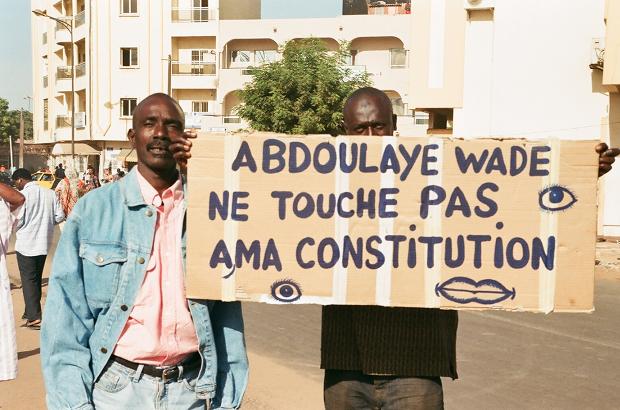

“Abdoulaye Wade, Don’t touch my constitution”. Dakar, December 2011 protests (Photo: Oualid Khelifi)

For the first time, the population is confronted with a leader obstinately clinging to power through illegitimate means. Even though the nation’s previous two presidents, Léopold Sédar Senghor and Abdou Diouf, held office for 20 years each, their re-elections were widely accepted, and so was their orderly exit, on the last instance of which Diouf peacefully handed over the presidential palace to his opponent Wade in the 2000 head-of-state race. Wade, however, appears determined to break with this tradition.

The “Constitutional Coup”

Since Wade’s announcement of his intention to amend the constitution and pursue a third term, political irony in Senegal found an inexhaustibly rich vein. For a start, it was Wade himself who had introduced the constitutional limit of two terms, and took pride in saying he would be the first to be subjected to it. However, the constitutional court ruled in late January this year that the term-limit amendment does not apply to him because he took power before it came into force, which would make his third term only the second according to the current constitutional text. “For a good while, he bragged about being the champion of democracy and alternation of power, his actions now reveal the exact opposite”, shouted to me one protesting student in Dakar.

The expression “constitutional coup”, already in circulation by this point, grew louder as soon as the internationally-renowned Senegalese musician, Youssou N’Dour, used it to react against the constitutional court ruling out his candidacy for the top job. The court argued that N’Dour’s dossier was not validated because, allegedly, not enough signatures were recognised on his application. The opposition called the court’s conclusion “laughable”, fuelling further unrest and furore against Wade’s “unabashed manipulation of independent state institutions” a political science researcher at University of Dakar said to me.

Angry young protesters in Dakar, December 2011 (Photo: Oualid Khelifi)

Wade’s legacy

Some observers argue that Wade’s will to carry social and economic reforms is undeniable. Since his coming to power in 2000, Senegal has not been the same. According to reports published by the IMF, the World Bank and several NGOs, economic growth averaged 4% a year, steadily higher than the previous decade. Fiscal management improved, government budgets increased, hundreds of new schools and colleges opened their doors, access to drinking water widened while child mortality rates dropped. Wade’s supporters continue to maintain he is a visionary without whom Senegal would have lagged way behind the third millennium.

How about his impact on the Senegalese polity? Wade wanted to take the fate of the West African nation into his own hands. Politically, he will be remembered “as the president who wrecked the pillars of the Senegalese democracy by overstepping over the constitution and running for the 3rd term” a Dakar-based political analyst told me. He has done much harm to the political tradition over the past 12 years by appointing six different prime ministers and “reshuffling the cabinet as often as he changes his booboo [West African sleeved robe worn by men]” I was told by a central government technocrat who has since joined the opposition in protest.

“Against expensive cost of life, Stand Up”. Dakar, December 2011 protests (Photo: Oualid Khelifi)

Each time a political team is sacked, Wade would centralise more decision-making powers and marginalise newcomers, even from his own party. Lack of political stability has delegitimised many echelons of the Senegalese institutions, whose frameworks have become centred on the president himself. Indeed, the change to term-limits is not the first time the constitution is meddled with: there have been 17 constitutional tweaks in eight years, some of them as flagrant as the 2008 change to the mandate of the lower house president from five years down to one, merely to get rid of Macky Sall, a political heavyweight who had fallen out with the ruling establishment.

Dakar turns its back on Wade

The “new era” symbolism of the year 2000, when Wade first came to office, certainly contributed to the hype surrounding his ascendancy and securing him the presidency. After 40 years of having Senghor and Diouf at the helm, both keeping the country together and relinquishing power gracefully, the Senegalese population felt ready for Wade’s Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS) whose fresh faces, discourse and rhetoric, it sensed, could bring about change and fulfil popular hopes.

Indeed, after 40 years of Socialist Party (PS) governance, most people were longing for a dose of change, or “Sopi” as said in Wolof, the ancestral language spoken by most Senegalese. But it was Dakar in particular where Wade’s Sopi slogans resonated the most in 2000. The capital, home to over 25% of the population, was a solid campaigning ground for Wade whose messages gave hope to hundreds of thousands of unemployed youth.

However, once in office, the newly elected president focused his Dakar development programme on infrastructure and set off on all sorts of projects to change the face of the capital: new coast Boulevard, new roads, a renovated port, new quays, a new airport, new runways and a new highway. The result, 12 years later, is that Dakar remains plagued with the same ills: high unemployment, rising prices, unbearable traffic jams and regular power cuts.

When I discussed the subject with Moussa, an unemployed resident of the capital, he remarked that “new roads and new everything is all well and welcome, but we cannot eat asphalt”. Indeed, Wade’s supporters could preach across the country about his achievements, but they cannot convince the jobless youngsters, living in derelict suburbs mostly untouched by Dakar’s infrastructure and economic upgrade plans, that much SOPI has taken place.

Plain clothes security agents clash with protesters in Place de l’Obélisque, Dakar December 2011 protests (Photo: Oualid Khelifi)

It was not ideology and decades of socialism which got Moussa to vote for Wade, and not for Diouf, in 2000: “It is not like people don’t care about political Right or Left, they just don’t distinguish them over here, liberal or socialist means nothing to me as long as there is no sopi, no job, no marriage, no future”, he said before vowing he will vote again this year, and “it will be against Wade regardless of the political colour of the opponents. Hope is what my generation is after, all we can do is drop in another name and hope for the best”.

Wade’s dangerous gamble

At his age – officially 86, though many believe he is well past 90 – Wade’s motivation to run for a third term remains intriguing. Is it pure folly of power, or his megalomaniac belief, described in wikileaks cables, that “nobody could do the job better” than he does? Is it because no one within his PDS party and political alliances has the faintest chance of winning? Or simply a final adrenaline ride for a delirious old man, as is often said in the local media?

Whatever the answer might be, Wade’s pursuit of the presidential chair seems reckless. Over the few weeks in the run up to elections day, at least half a dozen people died and hundreds got injured. Also, unluckily for Wade, the Dakar-centrist nature of Senegalese politics has set a trend for the rest of the country and violent protests have since spread everywhere.

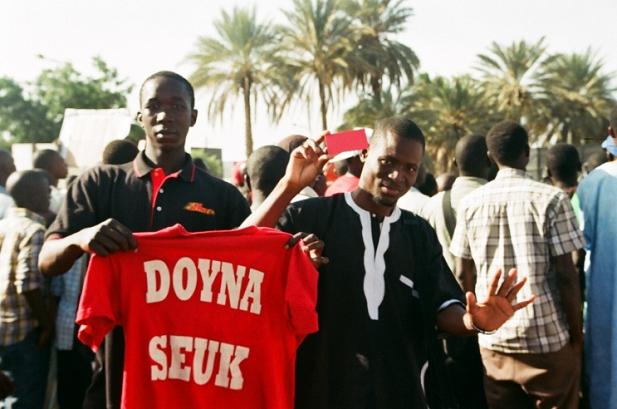

Movement Doyna Seuk, “it is enough” in Wolof. Dakar, December 2011 protests (Photo: Oualid Khelifi)

Moreover, emerging youth movements, which campaign beyond partisan divisions have created a wide platform of opposition against Wade. Movement M23 has managed to knit a strong web of civil society organisations and has been staging defiant monthly protests on the 23 of each month since June 2011. Another thorn in Wade’s side is the Y’en a Marre ( “Enough is Enough” in French) movement which managed to gather young professionals, students, rappers and unemployed masses under the flagship of “citizenry”. Doyna Seuk (“It’s enough” in Wolof) is also another very active and popular apolitical movement which stands against Wade in favour of promoting democratic values.

These groups, at times accused by security forces of leading “insurrectional plots”, have threatened to mobilise large masses against Wade should he cling to power after the 26 February. While most observers agree on their capacity to do so, Wade’s clan and security forces inexplicably do not perceive any palpable risk of descent into widespread violence.

“Tekki and M23 movement: Wade, get out”. Dakar, December 2011 protests (Photo: Oualid Khelifi)

Beside fierce opposition from popular movements and civil society, Wade has also suffered severe political loss of support. Once in his PDS ranks, Idrissa Seck, Macky Sall and Moustapha Niasse, three former prime ministers to name a few, are now beacons of the opposition, and some are even presidential contenders.

So far, the death toll of the recent riots, although the subject of varying estimates, has reached 10. Up to 5000 activists have been protesting for several consecutive nights outside the presidential palace. As the election approached, the general population seems to be pulling out of protests out of fear.

If all factored in, the incumbent leader should not stand a chance of escaping electoral defeat in tomorrow’s election. However, many Senegalese fear the old man’s canniness and are cautiously waiting for events to unfold. This week, rumours have been circulating that the regime is planning to issue reports of violence across the country first thing on Sunday morning to deter people from venturing out to vote. According to some, a low turnout would certainly favour Wade, and he might very well win without fraud, relying on scaremongering instead.

One Senegalese taxi driver drew my attention to Wade’s comments in 2000, when as a new president he said that his predecessor should receive a Nobel Peace Prize for having surrendered to elections’ results. “I do not think he will ever win a Nobel Prize, it might be violence that he wants, but we won’t give it to him. We are not Ivory Coast, chaos and fiasco are not in our blood”, the taxi driver said as we parted.

Leave a Reply