Inside the Saharawi Refugee Camps: Is the UN part of the problem? Special Report

New in Ceasefire, Special Reports - Posted on Thursday, June 20, 2013 18:45 - 2 Comments

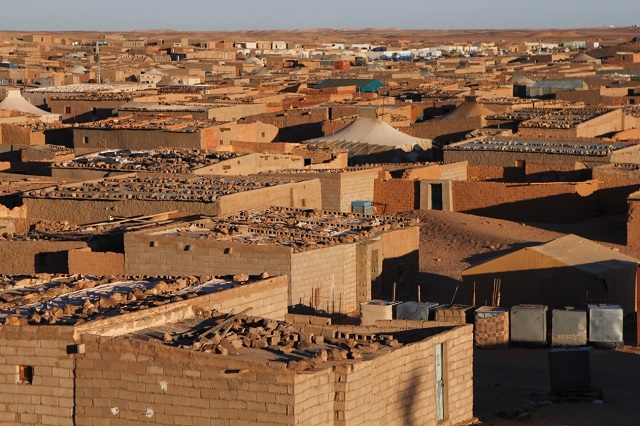

Landscape of Bojador, one of the Saharawi refugee camps (SADR, Algeria). ©Ángel L. Martínez

International aid has kept the needs and hopes of the Saharawi refugees going for almost four decades of exile. Dispensaries at the Navarra Hospital (Tifariti) are filled up with medicines sent by humanitarian agencies. Tifariti lies east of the Moroccan military wall dividing the territory, in the northern region of the so-called liberated zones of Western Sahara which is administered by the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR).

Medecins du Monde and the local authorities are responsible for the distribution of medicines channeled from the Spanish Agency for Cooperation and Development (AECID) both in the liberated zones and in the refugee camps (south-west Algeria). The Spanish government’s official humanitarian body has been actively involved in assisting the Saharawi population since the ceasefire and Settlement Plan signed in 1991.

Ali Salem, director of the hospital in Tifariti, explains: “The Spanish people have shown solidarity towards the Saharawi population but its government doesn’t take the political approach that it should. The Spanish politicians only support the Saharawi people when they run for elections.”

Entrance of Navarra Hospital in Tifariti (liberated territories, Western Sahara) © Angel L. Martinez

Although Spain is the world’s second largest bilateral donor (after Algeria) funding humanitarian aid in the Saharawi refugee camps, its political role in the conflict is not overlooked by either the refugees or the local authorities. Brahim Mojtar, the SADR minister for Cooperation, whose headquarters are 300 km south of Tifariti, and more than 7 hours away by 4×4 in the harsh Algerian desert, recognises the part played by Spain: “Historically and politically, Spain is responsible for the situation of our refugees and that is why it’s providing humanitarian aid.”

That is to say, Spain administers humanitarian aid as a guilty acknowledgement of its inability to find a political solution to unlock the stalemate in Western Sahara. Moreover, Buhobeini Yahia, president of the Saharawi Red Crescent (SRC) – the Spanish agency’s local partner in the camps- claims Spain has even a greater responsibility: “According to international law, Spain is the administering power in Western Sahara. So the Spanish funding contribution is minimal when you consider its political responsibility of more than 92 years of colonisation and its ties with Morocco.”

However, Spain is not the only state donor politically involved in the conflict. The United States is the world’s largest funder to the World Food Program (21% in 2013), and the WFP is the UN Agency in charge of the food security in the camps. “It’s easier for the UN Security Council to fund international aid than to pressure Morocco through political means,” says the Saharawi Prime Minister Abdelkader Taleb Omar. Referring to the veto against a political solution he continues: “France, member of the UN Security Council, doesn’t want to force Morocco to respect international law or UN resolutions.” As member of the EU, France also funds food aid to the refugee camps through the European Commission for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (ECHO), which contributed with 15% to the WFP this year.

Distribution of food aid in Smara, Saharawi refugee camps (SADR, Algeria). © Angel L. Martinez

The UN’s politics have a daily impact on the refugee camps. “According to Algeria and the local authorities there’re 165,000 refugees, but the UN acknowledges only 94,144. Although there’s a big gap between the two estimates, a rough figure of 125,000 refugees living in the camps has been agreed,” explains Ventura Rodríguez, who’s responsible for the programmes at AECID.

The number of refugees has always been a contested issue. While the UN agencies estimate a lower number than the figure registered by the Saharawi government, and has pressured the authorities to conduct a census, the SADR argues the census will only take place upon repatriation as was agreed in the Settlement Plan in 1991. Meanwhile, the Eurozone crisis has dramatically reduced the basic food basket available to the refugees.

According to the Saharawi government, the UNHCR estimates that 42,000 tons of supplies are needed to cover the basic food basket in 2013 yet only 13,000 tons have been delivered so far this year. “This shortage, together with the 60% cuts in regional aid received from Spain, has provoked a rise in anaemia among the population at risk: children under 5 and pregnant women,” the Minister for Cooperation explains. “We earn little but it’s enough. We don’t need to worry about food, as the state provides it,” an ambulance driver at the Hospital in Bojador, Salek Mohamed, replies when asked about needs in the camps. He reflects what many perceive to be a damaging dependency on aid among the population.

Indeed, after thirty-eight years chasing an ever-delayed solution, the long wait of the refugee population has also affected NGOs’ activities in the field. They face the dilemma of providing emergency aid while also being part of the problem of perpetuating the status quo. Abdel Fatah, a local technician in the water-treatment plant, comments: “We first created facilities for the short term as we thought our return to Western Sahara was imminent, but then we had to build a wall to cover these infrastructures once we realised we were going to be here for a longer period.”

The SADR’s Ministry of Water and Environment works alongside the Spanish NGO International Solidarity (Solidaridad Internacional) on projects related to water supply and sanitation. It has been severely hit by the cuts to international aid this year, receiving 80% less than in 2011.

Surroundings at the water-treatment plant in Smara (SADR, Algeria). © Angel L. Martinez

The insider politics surrounding international aid also influence the performance of cooperation and development activities. José Girón, an expert at Solidaridad Internacional, explains the decision-making process: “There’s just one technician but dozens of supervisors. This structure improves coordination but slows down our work. We have to discuss a lot before making a decision and needs are changing constantly.”

The long term refugee situation has brought changes to work distribution and salaries. Local NGO workers are paid a salary, whereas Saharawi technicians working for the relevant ministry only receive “incentives” – Saharawis working for NGOs gain more than four times the wages of colleagues working in the Saharawi public sector, creating frictions between Saharawi professionals with the same qualifications.

“This is the world’s longest crisis after the Palestinian one. No-one will find a (natural) exodus from either the sea side to the desert or from the north to south. We are refugees because of a political problem and not due to famine or a natural disaster,” states Buhobeini Yahia, President of the Saharawi Red Crescent. Many of the parties involved in international aid put it plainly, suchas Abdel Fatah, who says: “Institutions funding development projects should invest their political effort in finding a solution to this conflict.”

Security measures in the refugee camps

The kidnappings of 3 Spanish expatriates in October 2011 struck at the heart of the SADR’s national security situation, and the recent eruption of instability in neighbouring Mali and Algeria has increased regional insecurity even further. The solution adopted by the UN and donor states has limited the mobility and functionality of NGO workers and called into question the ‘raison d’être’ of cooperation itself.

The Spanish Agency for Cooperation and Development (AECID) recommended that NGOs evacuate immediately from the camps in 2011. After the kidnappings, the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs urged expatriates to cease their work in the camps and to reduce their activities to IN/OUT visits, that is, working from distance. “Obviously, organisations may follow such recommendations but these measures deeply determine the effectiveness of our activities,” asserts Álvaro López Criado, a technician working for Medecins du Monde Spain, and vice-president of Engineers Without Borders (ISF).

UNHCR car in Awserd, Saharawi refugee camp (SADR, Algeria) © Angel L. Martinez

Like Medecins du Monde, all Spanish NGOs followed the red lines drawn by the Spanish government. “Security measures weren’t visible before. Security was focused on the periphery, whereas now we’ve reinforced the center too,” comments Brahim Mojtar, Minister for Cooperation. However, according to Ventura Rodriguez, there was a vacuum in security with regards to NGO workers until the kidnappings took place.

The UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) is meant to be the international body responsible overseeing security both in the occupied territories, controlled by Morocco, and in the Saharawi refugee camps, administered by the SADR. Yet, the MINURSO headquarters are located in Layyoune, controlled by Morocco, whereas the chief of the UN agencies in charge of coordinating international aid is based in Algiers (Algeria), creating a political vacuum that leaves aid workers to their fate.

As Spain was the only donor state mobilising its personnel, some accounts found political interests behind that decision. “The Spanish government has shown certain rapprochement towards Morocco since the decision of evacuating the Spanish workers only undermined Saharawi interests,” asserts the SADR’s Prime Minister, Abdelkader Taleb Omar.

However, other foreign NGOs such as the Norwegian Aid Church (NAC) followed the Spanish example and withdrew their workers after the French intervention in Mali and the In Amenas kidnapping in Algeria, both in January 2013. Consequently, the Saharawi local authorities decided to evacuate all non-vital personnel from the camps. That measure included visitors in the camps or attendees to events such as Artifariti’s Sahara Marathon.

Aiming to address the UN’s poor security measures, the AECID channelled €640,000 to fund the programme ‘Saving Lives Together,” alongside ECHO, to increase security in the refugee camps. The UNHCR has been implementing this new strategy for the past two years. Security measures have focused on building a 1km-long, 3m-high, wired, fenced wall to protect the aid workers’ residential complex, as well as a similar defence system in the UNHCR headquarters where different UN Agencies and organisations are based.“This new strategy has restricted the already limited private life and the lack of personal contact with the Saharawi population outside the professional sphere,” complains José Girón, official technician at Solidarity International.

UN wall protecting the aid workers’ residential complex in Rabouni (SADR, Algeria) © Angel L. Martinez

The UN programme ‘Saving Lives Together’ has also appointed a security adviser, responsible for the supervision and management of security workshops as well as the escort and check-points effectiveness in each wilaya (region), supervision of the official curfew and the restriction of movement of expats in Rabouni. In the long run, the security programme may lead to increased hiring non-European expats, nationalising aid work teams or turn the follow up on-field operations into eventual missions run from the headquarters.

Meanwhile, the current UN security advisor states that “security has relatively improved but the threat is still present due to the instability in the region.” However, aid workers consider that these measures psychologically affect their lives and work. “It’s unfortunate that the unrest and tension in the region influences the NGO community’s ability to provide necessary aid to the camps,” says Eirik Kirkerud, NCA responsible for the Western Sahara project.

Humanitarian and development activities are also being affected by the new security measures. This might lead to a nationalisation of aid workers whereby Saharawis would take upon NGOs and UN agencies activities on the ground. One may ask about the part played by the UN and its Mission. Since the exchange of prisoners of war and the verification of the ceasefire in 1991, MINURSO has been incapable of providing safety and security for both refugees and aid workers in the refugee camps while it turns a blind eye to the ongoing human rights violations in the occupied territories in Western Sahara.

[VIDEO] El rumor del desierto:

2 Comments

Inside the Saharawi Refugee Camps: Is the UN part of the problem? | Idler on a hammock

[…] Saharawi people suffer. Since escaping the Moroccan bombs of napalm and white phosphorus in 1975, up to 165,000 Saharawi refugees have lived in camps of tents and adobe constructions in the driest corner of the […]

[…] via Inside the Saharawi Refugee Camps: Is the UN part of the problem? | Ceasefire Magazine. […]