Anarchist without Adjectives: Why Rudolf Rocker still matters Ideas

Ideas, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Thursday, April 3, 2014 11:01 - 0 Comments

If you think you know something about trade union history in the UK, yet offer a blank stare at the mention of the name Rudolf Rocker, then you don’t know what you think you know, for Rocker was a vitally important, if generally ignored, part of the history of trade unions in London, specifically, and in the UK in general.

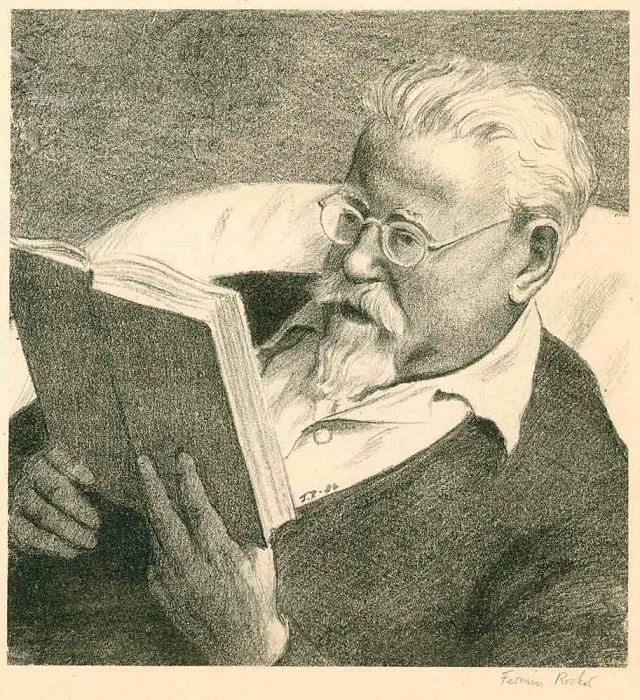

Who was Rudolf Rocker? He was a German immigrant and anarchist who lived in the UK, mainly in London, from 1895 to 1914 when he was interned as an “enemy alien”. During his time in London, he edited a Yiddish anarchist newspaper, Arbeter Fraynd, and the journal Germinal. Both publications reached thousands of Jewish workers, many of whom were in London’s East End where Rocker lived and where he was ultimately central to a huge transformation of the lives of East End Jews.

From 1880 to 1900, the Jewish population of London almost trebled from 46,000 to 135,000. Most of the new immigrants, many fleeing persecution in Russia and Eastern Europe, lived and worked in and around Whitechapel. The sweatshop conditions of the rag trade in which they worked were appalling, even in the context of the general conditions of workers at the time.

Rocker, along with his partner Milly Witkop and other Jewish anarchists, spent more than a decade building independent trade unions amongst those workers. The challenge was huge; the Yiddish-speaking immigrants fleeing pogroms had long faced levels of persecution and often a complete lack of any formal education.

In 1906, Rocker and the Arbeter Fraynd group established the Worker’s Friend Club on Jubilee Street. The club was open to all workers and focussed largely on workers’ education and self-education. Rocker and other anarchists spoke regularly on a range of topics.

The first stirrings of trade unionism amongst these Jewish workers came in 1906 when garment workers went on strike against their conditions, before a lack of funds saw them return to work. Rocker and his allies redoubled their efforts as the first signs of what would become the Great Unrest emerged in Belfast.

The 1907 Belfast docks strike, led by James Larkin, saw workers from both sides of the city’s sectarian divide come together to fight against their employers. A combination of attacks on Larkin from the leaders of his union in Britain and the strength of the conservative institutions in the city divided the working class once again and the movement fell back into sectarianism. However, it was the first shot across the bows in a conflict that would become a veritable class war three years later.

When Welsh miners took mass strike action in 1910, the Great Unrest had begun. Transport workers, particularly dock workers, took action across Britain in 1911 – but the centre of the conflict was in Liverpool. Over the two years, miners, dockers and others defended themselves against police and army violence and secured improvements in their working terms and conditions.

In May 1912, the action restarted in London as dockers took action again. As 80,000 went on strike, in what was supposed to be a national action, they soon realised they were on their own, receiving no solidarity from others in their own union. However, they did receive solidarity from an unexpected quarter.

In April of that year, Rocker and the Jewish trade unions’ moment had come. As a strike broke out amongst Jewish tailors in the West End, their work started to come in to the East End. Rocker and the Arbeter Fraynd decided to support the strike and called a meeting on 8 May. 13,000 workers, many of them not impacted by the strike in the West End, came to the meeting and decided to take action themselves.

The newspaper came out daily, meetings were held on a regular basis with speakers including Peter Kropotkin supporting the workers, funds were raised and, by the end of the month, the employers caved in and granted them their demands. The improvements that were achieved all but wiped out the sweatshops of Whitechapel.

The docks’ strike was continuing and failing, families were being starved into submission. The victorious Jewish workers decided to do something about it. They travelled the short distance to the docks and offered to take in the children of the largely Irish Catholic dockers. The docks’ strike was lost, but bonds of solidarity were forged that lasted a generation and beyond.

Twenty-four years later, those bonds were at the core of the anti-fascist mobilisation in Cable Street that prevented the British Union of Fascists marching through the still-predominantly Jewish area. Historian Prof Bill Fishman, who witnessed the events of 1936, said “It was moving to me to see bearded Jews and Irish dockers side by side as comrades.”

What Rocker achieved has some lessons for everyone trying to organise today. First, the concrete results he secured debunk the oft-repeated myth that anarchists don’t organise. Second, he epitomised the kind of leadership that anarchists can accept: he organised, he taught, he led by example, yet never tried to take control.

Moreover, Rocker not only showed that it’s possible to organise even the most excluded groups in society, but how to do it: you have to learn their language; you have to become one of them, however difficult that may seem – the way a German became an anarchist “rabbi”. It’s no use sitting in an office or organising an event and expecting people to come to you, you have to go to them.

The entire Great Unrest period was defined by an idea called syndicalism – trade unionism without political parties. The movement was worldwide, with syndicalist unions emerging first in France, then spreading across Europe to China, Latin America and, in the form of the Industrial Workers of the World, to the US and Australia. The movement was strongest when everyone acted together; it was weakest when political considerations and negotiations took precedent over action and solidarity failed.

With the constant attacks on the trade union movement in the UK from the Coalition government and no sign that Labour will do anything to change the anti-trade union laws, unions need to learn once again to stand on their own feet. By focussing on recruitment and organising and building solidarity, we can rebuild a movement that’s bigger and stronger than it’s ever been.

With the constant attacks on the trade union movement in the UK from the Coalition government and no sign that Labour will do anything to change the anti-trade union laws, unions need to learn once again to stand on their own feet. By focussing on recruitment and organising and building solidarity, we can rebuild a movement that’s bigger and stronger than it’s ever been.

If you live in South London, you can listen to Donnacha’s talk about Rudolf Rocker at Freedom Books’ launch of a new edition of Rocker’s ‘Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism’ on The Circled A Show, on Resonance 104.4 FM, at 9pm on Wednesday 9 April. Everyone else can listen online – live on the Resonance FM website or on the Circled A website a few days after the broadcast.

Leave a Reply