Review | ‘Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens’ by Richard Seymour Books

Books, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Wednesday, April 3, 2013 11:40 - 4 Comments

At one of the numerous deification ceremonies after the death of Christopher Hitchens in December 2011, Stephen Fry described the author and journalist as ‘a hero of the mind.’ A year earlier, Richard Dawkins had labelled him ‘a giant of the mind and a model of courage,’ and adorably chose him as ‘my hero of 2010.’ Like the historian Simon Schama, Dawkins recently claimed that Hitchens was ‘too complex a thinker to be placed on a single left-right dimension. He was a one-off: unclassifiable.’ Hitchens was supposedly, like the god of the Christians, beyond comprehension.

While in the process of forming these descriptions, it’s quite possible that Fry and Dawkins were reflecting on the time Hitchens told Adam Shatz from the Nation that ‘If you’re actually certain that you’re hitting only a concentration of enemy troops [with cluster bombs] … then it’s pretty good because those steel pellets will go straight through somebody and out the other side and through somebody else. And if they’re bearing a Koran over their heart, it’ll go straight through that, too.’ The 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths which predictably followed, were also deemed ‘pretty good’ by Hitchens. His heroism, then, clearly knew no bounds. One thinks of Achilles.

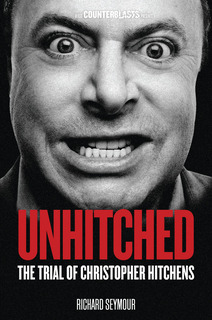

But these views, though certainly dominant amongst Anglo-American intellectuals, are not shared by the Marxist writer Richard Seymour. Though not quite a biography, Seymour’s Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens (recently attacked by the ‘left’ New Statesman and Independent) traces with some detail and subtlety the ideological changes of its boisterous, self-centred, and deceitful antagonist. The book’s central argument is that ‘not only was Hitchens a man of the right in his last years, but his predilections for a certain kind of right-wing radicalism … pre-dated his apostasy.’

Considering Hitchens’ persistent defence of Rudyard Kipling, his call for ‘humanitarian intervention’ towards the end of the Gulf War, and his 2007 defence of the Tunisian government (‘the most civilised’ dictatorship in the Middle East), Seymour reminds his readers throughout the book how Hitchens often defended his contradictory views by calling them ‘ironic’ or ‘dialectical,’ cautiously generalising them to avoid rebuttal: He correctly argued that Bill Clinton’s bombing of the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical plant was a war crime, but claimed with a straight face that Clinton was bravely resisting Serbian ultranationalism in Yugoslavia.

Hitchens wasted more time by writing his infamous Vanity Fair article, ‘Why Women Aren’t Funny’ (with the exception of those who are ‘hefty and dykey or Jewish, or some combo of the three,’ he eloquently clarified). Why, exactly, he had found it necessary to share this with the world will remain a mystery. Likewise, his enthusiastic opposition to particular reproductive rights is complemented by his social Darwinian praise of the abortion by nature of ‘deformed or idiot children who would otherwise have been born.’ How heroic.

It’s quite possible, however, as many argue, that Hitchens is not worth much consideration, so blatantly vile were his political and journalistic allegiances. But while it may be true that he isn’t worth thinking about, Hitchens is certainly worth talking about, not least because of his considerable and virulent influence in Britain (especially among young and relatively privileged ‘atheists’). Seymour’s essay – part of Verso’s Counterblast series, which aims to ‘challenge the apologists of Empire and Capital’ – should consequently be seen not just as an exposure of ‘the Hitch,’ but also as a highly valuable document in the continued efforts nationwide to increase the level of public political engagement, countering the temptations towards sticking solely to secluded, insular debates about the problem of evil, the afterlife, and so on.

Seymour traces Hitchens’ potential to be the author of such esteemed columns back to his formative years. He was ‘precociously articulate,’ reading widely though showing a ‘preference early on for literary fiction over, for example, the social sciences, for which it seems probable he had no aptitude.’ In his literary criticism, Hitchens abhorred any kind of ‘Third Worldism’ or ‘negritude,’ since he was ‘unwilling to tolerate the erosion of prestige that such criticism inflicted on the canon.’ He even argued in October 1992 that 1492 was ‘a very good year’ because of the progress in the American colonies which accompanied the genocide of its native population.

Seymour consequently susses that, in his literary and political commentary, Hitchens viewed indigenous life simply as ‘raw material’ for the ends of ‘progressive’ colonisation. Echoing points from his brilliantly argued (though poorly titled) The Liberal Defence of Murder, Seymour writes that it’s of little surprise that Hitchens exploited terms like ‘war on terror’ and ‘humanitarian intervention,’ and that, when reading essays on Orwell or Paine, he ‘proved stunningly literal and obtuse, as well as lacking in suppleness when dealing with someone who was too critical of one of his saints.’

All of these attributes echo with some force in Hitchens’ writings on religion, for which he is most famous. But Hitchens was at best ‘a poor atheist,’ for Seymour, making ‘secularism seem uninteresting and materialism incondite.’ Seymour detects the important role of opportunism in Hitchens’ efforts to become a renowned ‘antitheist,’ observing as he did the popularity of Harris, Dennett and Dawkins. His most celebrated book on religion, which bears the provocative and daring title God Is Not Great, ‘works as an entertaining expatiation of the sins of imperialism and indeed of capitalism.’ He shared with many of the ‘New Atheists’ the belief that, ‘in terms of egregiousness, all religions are equal, and Islam is more equal than others.’

Shamed and disgraced by his politics and journalism, religion became an easy target for Hitchens (and, as Mary Midgley points out, for many ‘who do not want to think seriously about the subject’). Unhitched cites Lesley Hazleton’s perceptive comment that ‘The bulls Hitchens chose were old and lumbering … so he was never in any danger. Kissinger, long out of power; the wounded Clinton; the pathetically, not-so-sainted Mother Teresa. And of course the most pathetic, lumbering bull of all, God.’

The book correspondingly demonstrates, with ample evidence, how Hitchens’ argument that ‘the worst kind of tyranny … is religious’ carefully distracts his loyal fan base away from state and corporate tyranny – far more dangerous cases, as Hitchens’ one-time debating rival, Chris Hedges, so persistently and insightfully points out (in ways which are, incidentally, far more eloquent than Hitchens, allegedly one of the greatest English writers since Orwell).

Seymour makes note of the intentionally impossible task the New Atheists have set religion (a task only slightly less ludicrous than the claim of many religionists that if science can’t explain the origins of the universe with absolute certainty, we should all turn straight to the nearest deity): that ‘the Abrahamic religions explain the incompatibility of the Creation story with the findings of contemporary natural and physical sciences.’ Hitchens’ philosophy of science is at times more absurd than the myths he spent his time debunking, since ‘Only by taking a severely reductive and literal approach to the Abrahamic texts, which would be a heterodox view among the religious, can one in all seriousness counterpose the Creation myth to quantum mechanics and find the former at fault for its incompatibility.’

Revealing his Marxist colours, Seymour argues that, by ignoring the social context in which the texts were composed, Hitchens ignores the less obvious fact that – alongside its largely genocidal tendencies – the Torah’s ‘description of the planets and other heavenly bodies, as not personal gods but objects susceptible to physical laws, was a revolutionary idea in its time.’ Though it is not at all clear that the notion of ‘physical law’ would have presented itself to the craftsmen of the Genesis myth, Seymour’s indictment of cultural and theological illiteracy on Hitchens’ part is nevertheless a highly convincing one.

And where Hitchens claimed that Wycliffe and Coverdale were burned at the stake for their Biblical translations, Seymour cites William Hamblin’s observation that the former died of natural causes, while the latter died ‘unburned in 1568 at the age of eighty-one.’ All of this, of course, is not to ‘side’ with religion over the New Atheists – Seymour rightly rejects both – it’s rather to demonstrate how ignorant and careless Hitchens was in being unable even to construct a coherent and accurate attack on some of history’s easiest targets.

Hitchens was also often filmed alongside fellow atheists Dawkins, Sam Harris (another staunch neoconservative), and Daniel Dennett – self-labelled the ‘Four Horsemen’ – discussing with wonder and awe the ‘intricate complexity’ and ‘stunning variety’ of the natural world, each of them providing their own view from their respective fields. But since the universe is so beautiful, why is it that the Horsemen largely failed to attend to the concerns of its most remarkable life form? The New Atheist’s Islamophobia, for instance, exhibits the ‘central feature[s] of racism,’ for Seymour: ‘essentialist thinking, ascriptive denigration, and demonology.’

Such bigotry was displayed by Hitchens on many occasions, most notably when he wrote after the November 2004 siege of Fallujah that ‘the death toll is not nearly high enough … too many [jihadists] have escaped,’ adding a couple of years later that ‘it’s a sort of pleasure as well as a duty to kill these people’ – one of the reasons why Norman Finkelstein once told me Hitchens is ‘worth zero.’ With similar compassion, Hitchens later spoke of Iran: ‘As for that benighted country, I wouldn’t shed a tear if it was wiped off the face of this earth.’ Indeed, for all his hatred of religion, Hitchens’ savage political attitudes often made the Lord of the Old Testament appear fairly soft-hearted.

Rather than uncritically associating Hitchens with the tradition of Reason and the Enlightenment, Unhitched intelligently characterises Hitchens’ rhetoric as similar to the ‘martial discourse that emerged on the right in World War I, was sustained by fascism in the interwar period, and had its consummation in World War II.’ To choose one particularly striking example, in July 2007 – still thinking up smart new ways to defend his position on Iraq – Hitchens claimed that the sight of people jumping from the crumbling towers of the World Trade Centre was ‘not that terrifying … That kind of thing happens in a war, it has to be expected in a war … you should reckon about once a week. Get ready for it.’

After the Iraq War was revealed without any doubt to be an unusually (though predictably) savage catastrophe, Hitchens ‘merely fantasised that the Bush administration was the equivalent of the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification, and he was shocked to find that they were selling out his just war,’ Seymour comments, before moving on ‘without ever having to really account for what he had done.’

Like the older Aldous Huxley, Hitchens ‘esteemed collectivism at least some of the time but never submitted to it himself,’ while he also ‘resented the rich and powerful but enjoyed their company.’ Hitchens’ critiques, observes Seymour, often focused on personality over policy. Even in his early days, he ‘had a tendency to revile the personnel of American statecraft without a great deal of emphasis on the structures of power.’ He pursued further self-serving policies by emigrating to the US in 1981, where he ‘positioned himself as an English radical amid compromising liberals,’ attending all the right parties and charming the sleek editors of the glossiest monthlies (the gorgeous Graydon Carter comes to mind).

But Unhitched does, inevitably, have some down sides. Early in his essay, Seymour disapproves of Hitchens’ view that Louis Althusser’s political philosophy was an ‘attempt to recreate Communism by abstract thought’ (a case of Hitchens ‘bowdleris[ing] the theoretical issues that he delved into’ out of ‘simple philistinism’). However, ‘Lenin’ Seymour’s own penchant for certain French Marxists (he has previously quoted and discussed Althusser at length) puts him on a peculiar kind of defensive here. A more sensible path to take would be to expose both the fraudulence of Hitchens as well as the ‘intellectual rubbish’ (as Bertrand Russell would call it) of Althusser’s work.

Seymour’s elevated prose can also often become tiresome. He finds special delight in ‘amanuensis’, ‘ouvrieriste’, ‘credenda’, ‘bilious’, ‘carapace’, ‘concupiscence’, ‘eristic’, ‘diapason’, and ‘emotionally potent oversimplification’ – a phrase of Reinhold Niebuhr’s, to whom he does not give credit (ironic, considering he uses it in the same paragraph he rightly condemns Hitchens for ‘sometimes appearing to borrow material from others and not always with attribution’).

But these, of course, are very minor criticisms. Seymour’s well known Marxist commitments rarely obscure his enjoyable and relentless attack on the deceitful image Hitchens and his friends constructed, meticulously revealing his confused use of the term ‘Marxism’ as at times meaning ‘a simplistic progressivist view of historical development,’ at other times ‘a crude materialism that had a tendency to flip over into idealism,’ and at yet other times as ‘a meritocratic ideology.’

Seymour is also one of a relatively small number of writers willing to call out Hitchens for what he was: ‘a terrible liar, in both senses.’ The book notes, for instance, how he lifted material for his essay ‘Kissinger’s War Crimes in Indonesia’ from Chomsky and Herman’s The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism. Though he omits Hitchens’ smearing of Chomsky, his defence of the Whitehouse’s extrajudicial killing of Anwar al-Awlaki and Osama bin Laden, and his praise of drone warfare more generally, Seymour covers in some detail Hitchens’ shameful attacks on Edward Said, his reaction to the 1974-5 Portuguese revolution, the Falklands War, 9/11, and the credit crunch.

Seymour’s essay, then, is ‘unabashedly a prosecution,’ carefully directing its readers through its core arguments, neither over-stressing nor over-simplifying its claims. It is never overwhelming in its scholarship and analysis (indeed, his heavy reliance on sources such as Tariq Ali leaves his trial open to the charge of unashamed bias), but it is by no means underwhelming either. It is simply whelming.

Though less engaging in its prose than Seymour’s 2010 polemic The Meaning of David Cameron, Unhitched is much more careful and attentive in its arguments, more willing to justify itself to the outsider. His trial offers the judge a well-researched and original indictment of one of the most contemptible and dangerously influential intellectuals in recent memory. It is now up to the jury, through the words of eager journalists, willing academics and a concerned public, to ensure the prosecution is heard loud and clear.

Though less engaging in its prose than Seymour’s 2010 polemic The Meaning of David Cameron, Unhitched is much more careful and attentive in its arguments, more willing to justify itself to the outsider. His trial offers the judge a well-researched and original indictment of one of the most contemptible and dangerously influential intellectuals in recent memory. It is now up to the jury, through the words of eager journalists, willing academics and a concerned public, to ensure the prosecution is heard loud and clear.

Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens

by Richard Seymour

Paperback, 160 pages

January 2013

$16.95 / £9.99 / $18.00CAN

Verso

4 Comments

Anti-Trot

Hitchens did god works and bad works, this is true.

The missionary position (the work about Teresa de Calcuta) is a master piece, and not easy to expose to the public.

Evan Milner

Elliot Murphy writes that Hitchens’ “enthusiastic opposition to particular reproductive rights is complemented by his social Darwinian praise of the abortion by nature of ‘deformed or idiot children who would otherwise have been born.”

Although Hitchens did indeed raise questions about the rights of the unborn vs. the rights of the mother, there was nothing “enthusiastic” about his doing so. To the contrary, in his Vanity Fair article of Feb. 2003 he concluded by reminding us that “the irresoluble conflict of right with right was Hegel’s definition of tragedy”. Likewise, characterizing his reference to “abortion by nature” as “praise”, rather than a brute assessment of the facts, is disingenuous.

Furthermore, exactly how Hitchen’s comments on the naturally occurring phenomenon of miscarriage can be construed as social Darwinism (as opposed to simply “Darwinian”) is a mystery, suggesting that the author either doesn’t know what social Darwinism means or, in his eagerness to denounce Hitchens, he simply doesn’t care.There are plenty of legitimate grounds for criticizing Christopher Hitchens without the need to distort his views.

Mr. Murphy’s claim that “while it may be true that he isn’t worth thinking about, Hitchens is certainly worth talking about” is especially apt since it perfectly describes his entire review: it manages to say a great deal but shows little evidence that any thought was involved.

“The New Atheism,” and Humanitarian Imperialism, & Question for Readers | wallacerunnymede

[…] https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/review-unhitched-trial-christopher-hitchens-richard-seymour/ […]

“Seymour’s elevated prose can also often become tiresome” – doesn’t it just.

Still little Richard did a man’s job dismantling the Socialist Workers Party for which the British Left should be grateful.