Arts & Culture | Remembering Juliano

Arts & Culture, Film & TV, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Monday, April 11, 2011 0:00 - 6 Comments

By Nihal Rabbani

By Nihal Rabbani

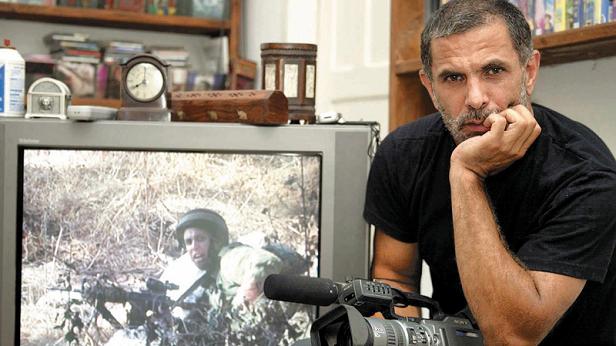

When I first heard that Juliano Mer-Khamis was killed last Monday, the announcement read like a misprint. Even though I knew it was true, I waited for someone to reveal that it was a hoax. Like everyone, I felt too stunned and bewildered to process this bizarre news before pausing for a few hours, numbed with disbelief.

Before night fell, the reality still hadn’t sunk in. I hardly knew anyone in Amsterdam who shared personal memories of him, as images of Jule’s (as everyone called him) intense face and loud, penetrating voice ran through my mind like shuffle cards. I tracked down a mutual friend in Haifa, who felt even more disoriented by the blow. After attending a memorial service held on the night of Jule’s death, he exclaimed, “We don’t even know how to deal with it!”

I emailed my friend’s wife, who I had met in Juliano’s company at our local Haifa pub and shared my grief with her. The next day, I contacted a mutual friend of Jenny’s (Jule’s wife), who I’d met in Palestine. By then, the recollections finally started to settle and I was ready to mourn him.

Friends who were close to Jule, others who casually knew him, people who had only heard of or admired him and all those who had hoped to, one day, collaborate with Jule at the Freedom Theatre – we were all struck by the same brutal, communal shock. His family extended beyond his lover, children, unborn twins, brothers and mother of his daughters. They were the Palestinian community in Israel, the Freedom Theatre in Palestine, friends from the local pub in Haifa, his many comrades and acquaintances spread throughout the world and the thousands of people who were touched by his cause after watching “Arna’s Children”.

I was alerted to Jule’s spark long before I’d ever heard of the work of his late mother Arna. The first time I saw him was during the height of the first Intifada in the late eighties, on my parents’ television screen in Holland. A particularly handsome and charismatic man of the theatre appeared, mesmerising and captivating the viewers as if he were juggling us with his hands. He demanded our attention with a cheeky twinkle in his eyes, as if to say, “You will never forget me”. Even though I was only nineteen years old at the time, I never did forget him.

At the time, he was one of the few people I’d heard of who came from a “Palestinian-Jewish” background. His heart had not yet been captured by Jenin. Jule was a street performer, an actor and a bohemian artist. He charmed the viewers with his complex story, which he was already sharing with the conviction that he was lucky to be in such a unique position. One thing that struck me is that he seemed fearless and invincible.

Jule explained that his parents were communists and that he was born into a “forbidden” love story that had turned sour. He spoke openly about being a former paratrooper in the IDF, concluding that his decision was influenced by the hostile manner that his Palestinian father treated his Jewish mother, which is something that I never heard him mention again.

Over the years, however, he claimed that he didn’t regret his “mistake” because it taught him to dissect Israeli society through the training he received from an elitist army unit. I had mixed feelings about his justification because I was aware of the malicious attacks that Israeli paratroopers perpetrated on innocent civilians. On the other hand, I acknowledged that when Jule came of age, he must have felt conflicted between two of the most volatile identities in the Middle East and that his Israeli high school environment peer-pressured him into picking the stronger side of the fence.

Whether or not I agreed with this, the truth of the matter is that if he hadn’t joined the military (which consequently placed Jule in prison for disobeying orders), I doubt he would have witnessed the injustices that prompted his conscience to eventually support the underdog. At best, Jule might have become a moderate Israeli who dodged his Arab roots, which still would have been a rebellious reflex towards his parents’ leftist views. He probably would not have been transformed into a proud Jewish Palestinian who celebrated both sides of his cultural, religious and ancestral identity.

In 1994, six years after his television appearance, I visited my parents’ home town, Haifa, for the first time. I met with Palestinian friends at an Israeli bar called ‘Olam Moze’, translated as ‘One World’, which was one of the few places that welcomed “Arabs”. When my friends mentioned that they had seen Jule perform nudist street theatre, I figured that he was the same guy I’d seen in the interview. Even then, he didn’t allow barriers to disrupt his artistic self-expression.

Exactly a year after my first trip to the ‘Homeland’ in 1994, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was shot dead. The peace trick vanished. The second Intifada started five years later and ended in 2004, which was the same year that I returned to Haifa. This time around, Palestinians from the diaspora (like myself) and residents who were reduced to being labelled as “Arab Israelis” felt even less welcome at Israeli establishments.

Places such as ‘Olam Moze’, which had shut down years before, no longer existed. But even if that café had been running, the hostile post-Intifada climate pointed us towards Palestinian-owned pubs, which didn’t exist a decade earlier. Along with the ensuing Apartheid, a revival of ethnically-divided hangouts emerged. From then on, Jule was always to be found at an Arab-speaking café when he wasn’t in Jenin.

But that’s not where we officially met. I first heard about “Arna’s Children” at the Amsterdam documentary festival in 2002, during the height of the second Intifada. The film was still in production and had been battling a number of complications. One evening, the producer walked into the festival café, looking distressed. When we asked her what was wrong, she announced that Juliano had just called from Palestine, informing her that one of the young actors from the Freedom Theatre (who was featured in old film footage in the documentary) had died in a suicide attack.

A year later – not long after his mother passed away and fifteen years following the infamous telly screening – I finally met Jule at the première of “Arna’s Children” in Amsterdam. He was at his peak. His first documentary had just been released, he had a young daughter with his girlfriend Mish Mish, the Freedom Theatre was experiencing a renaissance and everyone wanted a piece of Jule.

He was sitting at a table with some friends of mine, who called me over. When we shook hands, Jule had a surprised and careful look on his face. He was polite, modest, even shy. On first impression, he was the complete opposite of the charged and vocal activist that I would come to know.

I told him about the television interview that hadn’t left my mind and joked that even in 1988, I could already tell that he was clearly insane. He responded – interrupted by loud chuckles – that he’d never met anyone with such an insane memory. At the time, a colleague and I were making a reportage featuring the film festival and we needed someone to interview. He was very accommodating and immediately made himself available.

When we finished filming, I noticed that there was something wrong with the sound. Jule was already late for his next interview and laughed, “You mean these two hours, which usually only take fifteen minutes – they were for nothing?” (As it happens, the local broadcaster wasn’t interested in this subject so never watched the footage. But I did keep the video tapes and decided to edit the material as an homage to Jule.)

Since the day we met, Jule never failed to mention my “crazy memory” to people he introduced me to. The camera woman who worked with us that day in 2003 had since become a friend. When I sent her a text message about what happened last Monday, she responded in disbelief, saying, “What terrible news, coming from such a beautiful and inspiring man.”

Following a ten-year absence, I returned to Palestine in 2004 and saw Jule each time I visited Haifa. A mutual friend invited me to a Palestinian café, where Jule would eventually meet his future wife Jenny. When Jule arrived, he pulled up near our table, parked his car halfway into the pavement, then had drinks with us while his daughter slept on his lap. Inevitably, he didn’t forget to inform my friends, “You know, this girl Nihal has the most amazing memory!”

Shortly after his relationship ended, something changed in Jule. Despite feeling gratified and empowered by his mother’s legacy, he appeared angered and frustrated by the obstacles that were beyond his influence. It might have been due to him dealing with so many deranged aspects of Israeli and Palestinian society. It could also have been due to him investing all of his energy into the Freedom Theatre, while the actors he trained were feeling anything but liberated by the occupation. Or maybe I was just starting to get to know him.

Despite being reckless, Jule had a deep sense of reliability. He dealt with the pressures of feeling responsible for people who were not living in a stable environment. I remember when his brother went missing, he dropped everything to go search for him, taking on the task of a father. He did whatever it took to keep his family together.

He also had a heart of gold. When I was down and out in Israel, I encountered racist landlords while searching for a place to live, who rejected me due to my Palestinian background. Even though he didn’t know me well at the time, Jule offered me his place to stay whenever he was out of town. I ended up finding a flat in Jaffa instead, but he was one of the few who had welcomed me into his home. He had a familiar Palestinian hospitality, well-preserved by those raised in exile but which had gone missing in the homeland. He enjoyed helping others, without feeling compromised or asking for anything in return.

Jule was also a difficult person to communicate with when he was feeling perplexed. He was audacious, confrontational, provocative and always had the last word. I started out as someone who admired his drive and resilience, who envied his ambitious nature and sense of responsibility, who loved his passion for theatre, who felt inspired by his persistence to evolve as a humanitarian – and, above all, who was drawn towards his uninhibited, wild edge – but then his combative moods occasionally gave me the urge to strangle him.

Jule’s feisty qualities, which regularly landed him in heated discussions and quick-tempered exchanges with others were the same traits that people loved about him. Ultimately, his rage helped him accomplish what his mother had started achieving ten years ago.

Following this conflicted period, Jule appeared to have had enough of Israel and the madness that it instilled in others. He did what any smart person would do: take a road trip to India, joined by his little girl. During this time, Jule’s dog was staying in Jaffa and I often saw him walking around with his head hung low, barely displaying his sad and bored face. It was as if he was waiting for his exciting and magnetic friend to return before he agreed to start wagging his tail again.

Jule narrowly escaped death in a motorcycle accident during his travels and I recall how relieved everyone was when news arrived that he and his daughter survived their injuries. That day, images of the time I saw him on telly flashed before me, when his adventurous eyes convinced the viewers that he could survive anything. This haunting memory hasn’t left my head this past week.

When Jule returned from India, he softened up. The sparkle returned to his eyes, he appeared calmer and seemed to have discovered new reserves of energy. He met his girlfriend Jenny, now his wife and mother of their son and unborn twins, whom I met myself through her best friend about a year later.

During the summer of 2006, which witnessed Israel’s attacks on Lebanon, we visited our friend in Nazareth for a weekend, which was one of the most memorable trips I took that year. This was Jule’s hometown, home to the largest community of Palestinians in Israel. I recall the city being in mourning because the municipality did not activate the war sirens when katyushas were being fired, simply because the downtown neighbourhood was inhabited by Palestinian residents. This resulted in the death of two children who were playing outside. Their father appeared in the headline news, blaming Israel instead of Hezbollah. Refusing to recognise that these casualties were a result of government-controlled racism, Israelis responded with national outrage.

While Zionists in Haifa and the Galilee abandoned their homes in an attempt to escape attacks from Lebanon, Palestinians stayed put. Maybe the memories and consequences of the Nakba were still too vivid in their collective mind? Or maybe it had just become clear who was attached to the holy land and who was not. Jule and Jenny stayed in their Haifa home; they didn’t run away.

The last time I spoke with a mutual friend before Jule’s murder, she told me that him and Jenny had gotten married and were expecting a child. It was the first time I’d heard Jule and Jenny’s news since I left Palestine and I was so happy for them. Their son is a year old now and probably won’t remember his doting father. But what saddens me the most is that Jule never got the chance to meet his unborn twins.

A few months ago, Juliano was in Amsterdam with his daughter Milay. The same four-year old girl who slept on his lap at the Palestinian cafe now spoke fluent Arabic and was selling DVD copies of “Arna’s Children”. What really upsets me now is that I never got a chance to speak to Jule one last time. I could only see the back of his head, as people kept swarming around him. Seven years after first meeting him, I could see everyone still wanted a piece of Jule. I decided I better stop standing around like a groupie and went home, thinking we could meet up before he left the country. As always with Jule, I thought to myself, “there will be another occasion”…

One week later, I still can’t believe that crazy, generous and passionate Juliano is gone.

Nihal Rabbani is a Palestinian chef based in Amsterdam.

6 Comments

Carolien

Anne Selden Annab

Nihal, of all the many articles, tributes and remembrances I have read about Juliano I like yours best.

Marrickville BDS Resolution Under Attack « KADAITCHA

[…] Ahmad’s video “US-Israel Trade: Espionage, Theft and Secrets..”‘ Remembering Juliano Recognising Palestine? by Ali Abunimah ‘The PA’s push for recognition of a Palestinian […]

Art and Politics The View from Lebanon – Ceasefire Magazine

[…] world has historically been a source of inspiration for art. Juliano Mer-Khamis, who was recently brutally murdered in Jenin, the Palestinian painter Ismail Shammout and Mona Hatoum, who has just presented her new […]

who+dares+wings

Very nice tribute! I met him in Goa with his daughter on that trip to India. He bought a used Royal Enfield motorcycle from the brothers who ran the guest house where I was staying. I agree he was “magnetic.” I had no idea he was a star in Israel and Haifa, but I knew there was something extraordinary about him from the way he carried himself. He exuded charisma and courage.

Juliano Mer-Khamis » Arts in Conflict

[…] the days following his murder many people felt the need to express their sorrow, and their anger. Nihal Rabbani wrote a beautiful personal account of her encounters with Mer-Khamis. Maryam Monalisa Gharavi […]

What a beautiful and moving tribute. And what a terrible loss.