How to remember Stalin: ‘The Collaborators’ (National Theatre) and ‘Building the Revolution’ (Royal Academy) Arts & Culture

Exhibition, New in Ceasefire, Theatre - Posted on Friday, December 16, 2011 0:00 - 0 Comments

By Musab Younis

‘Killing my enemies is easy,’ says Stalin. ‘The challenge is to change the way they think, to control their minds.’ His enemy – Mikhail Bulgakov, the writer – cowers on a chair.

This is actually happening onstage in London, in a new play by John Hodge called The Collaborators, which is showing at the National Theatre (and in cinemas through the ‘National Theatre Live’ scheme.) The Collaborators is John Hodge’s first play. He has previously adapted Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting for film, and written the screenplay for The Beach and Danny Boyle’s short film Alien Love Triangle. As a screenwriter Hodge has been, for better or worse, successful. With The Collaborators he makes the sideways leap into London theatre.

Mikhail Bulgakov, fiercely independent writer of the The Master and Margarita, is assailed one day by the Soviet secret police and encouraged to write a play for Stalin’s birthday. The rest of the play follows his tortuous decision-making, decline in health, and imagined encounters with Stalin in which he discovers just how difficult it is to be an autocratic leader. Interspersed are scenes from the improbably melodramatic production he is writing about Stalin’s youth. Other characters – a jovial secret policeman, Bulgakov’s wife, a young man who lives in a cupboard (perhaps the unfunniest joke of the play) – regularly feature, beseeching Bulgakov in various ways. The set, in the National’s small Cottesloe Theatre, is a kind of narrow walkway, mildly chaotic and surrounded on all sides by the audience.

It is obvious what this is supposed to be: an enjoyable, disorienting look at what it was like to be a writer under Stalin, and about what might drive a successful though pressured writer like Bulgakov to write a propagandistic play like Batum, told with surreal, dark and distinctly Bulgakovian humour. On some of these points it succeeds – it is watchable and entertaining in parts, and the performances are good enough. But mostly it unfolds like an anodyne morality play about the Soviet Union that has been simplified for children, with thudding pantomime humour of the type that even most children find distasteful and patronising. By the end, Simon Russell Beale’s Stalin-as-David-Brent performance has racked up far more cringes than laughs, and there is an astonishing unselfawareness to some of the dialogue (see the line quoted above, which is neither untypical nor improved by context.)

The National tells us that The Collaborators ‘depicts a lethal game of cat and mouse through which the appalling compromises and humiliations inflicted on any artist by those with power are held up to scrutiny.’ This eye-aching sentence, piled with subclauses, does well to convey a sense of the play itself; though to be fair to Hodge, the play doesn’t see itself as an intellectual shifting of theatrical paradigms and the National hasn’t exactly sold it as such (though some reviewers have). What has been commissioned is an unchallenging, fast-moving take on the Bulgakov-Stalin relationship. This has, in the end, probably been delivered.

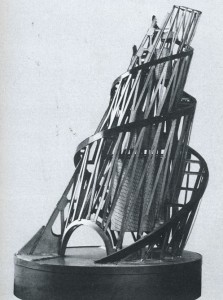

At the Royal Academy of Arts in London, a circular leaning tower has been constructed in the courtyard. The tower is Vladimir Tatlin’s ‘Monument to the Third International’, the wondrous but never-built Bolshevik answer to the Eiffel Tower, scaled down 1:40. The occasion is the exhibition, ‘Building the Revolution: Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935’, based in the Sackler Wing of what must be London’s most confusing gallery space. (You can get to the Sackler Wing by using a circular staircase that is hidden near the first-floor gift shop, or by using a glass lift that is invisible if it is on a different floor.)

At the Royal Academy of Arts in London, a circular leaning tower has been constructed in the courtyard. The tower is Vladimir Tatlin’s ‘Monument to the Third International’, the wondrous but never-built Bolshevik answer to the Eiffel Tower, scaled down 1:40. The occasion is the exhibition, ‘Building the Revolution: Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935’, based in the Sackler Wing of what must be London’s most confusing gallery space. (You can get to the Sackler Wing by using a circular staircase that is hidden near the first-floor gift shop, or by using a glass lift that is invisible if it is on a different floor.)

The exhibition mostly consists of two types of photographs: the original black-and-white little images, taken from Schusev State Museum of Architecture’s archive in Moscow, and large colour images taken by photographer Richard Pare. The small, old photographs show the buildings when they were new, while Pare’s pictures display the buildings in varying states of decay.

There are pictures of the renowned architect Konstantin Melnikov’s house in Moscow, completed at the end of the 1920s, which consists of two intersecting white cylinders cut through with diamond-shaped windows. With the rise of Stalinist architecture, Melinkov retreated into this house, painting portraits and teaching. Many of the buildings on display were designed schools and workers’ clubs, and include the famous Rusakov Workers’ Club, a constructivist landmark with its protruding, fan-shaped auditoriums.

Alexey Shchusev is presented as the enterprising architect who designed Lenin’s mausoleum in Moscow which (in its current version) was finished in 1930. It is a curiously appealing arrangement of red, grey and black granite blocks, forming a low-lying, Lego-shaped mass in which Lenin’s body is still housed. The interior chamber, displayed here in some of Pare’s most impressive photographs, is mostly polished black granite with a dazzling red zigzag running around the middle.

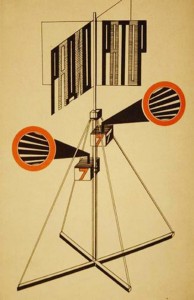

Other highlights include the designs for propaganda kiosks by Gustav Klutsis, which date from the early 1920s, and in particular his ‘Design for Loudspeaker No. 7’ whose orange-and-black colour scheme and circle-line combinations must have inspired Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Klutsis’s designs were closely associated with the Soviet state – he taught at the state-run art school VKhUTEMAS until 1930 – but it wasn’t enough to keep him in the clear; in early 1938 he was arrested and, as was later confirmed, executed in the purges. The same might have happened to Liubov Popva, whose cubo-futurist artwork is among the best in the exhibition, but she died in May 1924, aged only thirty-five.

Other highlights include the designs for propaganda kiosks by Gustav Klutsis, which date from the early 1920s, and in particular his ‘Design for Loudspeaker No. 7’ whose orange-and-black colour scheme and circle-line combinations must have inspired Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Klutsis’s designs were closely associated with the Soviet state – he taught at the state-run art school VKhUTEMAS until 1930 – but it wasn’t enough to keep him in the clear; in early 1938 he was arrested and, as was later confirmed, executed in the purges. The same might have happened to Liubov Popva, whose cubo-futurist artwork is among the best in the exhibition, but she died in May 1924, aged only thirty-five.

The Telegraph, in its review of this exhibition, resuscitated a panapoly of Cold War-era clichés: ‘a society notoriously based on fantasy’, ‘an ugly mess’, ‘ill-fated artistic revolution’, and so on. In truth, of course, any such conclusions are impossible to draw. At best the exhibition is a bibliography-with-pictures, giving you a set of names that you can research properly later along with faultless photography from Richard Pare.

But there is no real sense of what it was like either to live in these buildings, or to design them, or to restore them now, or to live by them as they decay. Partly the exhibition is hampered by what is, despite an ambitious refurbishment, a highly conservative gallery space in the Royal Academy. And partly the curating has been lax: there are effectively no videos, no pedantic digressions, no use of sculpture or computer modelling, that would have made the subject come alive. We are simply presented with a series of pictures in rows and a courtyard model.

Like The Collaborators, ‘Building the Revolution’ takes advantage of a renewal of interest in the Soviets but, in its half-hearted treatment of the topic, is finally disappointing and even frustrating. It is not just the case that there is much more to be said about Bulgakov or early Soviet architecture – curator and writer would surely agree – but that, even considering the little time or space one has to convey something in an exhibition or play, these are ultimately disappointing and unambitious results. Hodge plays his subject for laughs – a risk that doesn’t pay off – while the Royal Academy ossify their subject, stripping it of the human context that makes it interesting in the first place and veering at times, with the constant old/new parallels and fixation on the strange and semi-exotic, dangerously close to cliché.

Leave a Reply