Radical Aesthetics The Art of Spectacle

Arts & Culture, New in Ceasefire, Radical Aesthetics - Posted on Monday, May 16, 2011 0:00 - 0 Comments

By Daniel Barnes

By Daniel Barnes

The arrival of spring hails the start of the great artworld circus that is the Turner Prize. The shortlist has already stirred the usual mixture of ill-conceived cynicism and giddy elation, so it is time to reflect on the cultural relevance of Britain’s most coveted art prize.

The big surprise this year is that there is no surprise, just a fair overview of the state of contemporary art, representing painting, sculpture and video. And there is nothing morally shocking, gratuitously offensive or recklessly vile about any of the works.

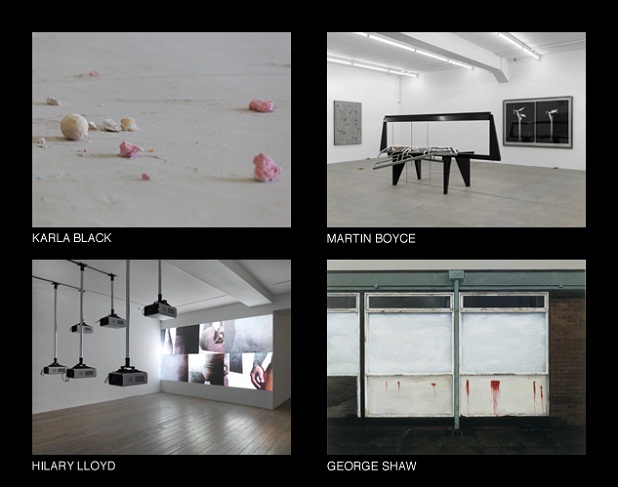

In fact, by previous years’ standards, the Turner jury has delivered a sedate, thoughtful and even conservative shortlist. We have George Shaw’s enchanting paintings of a Coventry council estate, Karla Black’s perplexing but humorous experiments in painting with cosmetic products, Martin Boyce’s innocuous sculptures inspired by modernist furniture, and Hilary Lloyd’s mystifying videos of building sites and men in underwear.

Although it features a little nudity and an unorthodox method of painting, this shortlist is long on talent and short on high jinks. Nonetheless, it has already ruffled a few feathers.

Since its inception in 1984, the Turner Prize has courted controversy. In that first year the prize was awarded for ‘English paintings’ by Malcolm Morley, which scandalised people who could not understand how an expatriate in the USA could win a prize for British art. Also that year, the Tate set the trend for the prize causing a flutter in the nation’s moral heart by including Gilbert & George on the shortlist. Since then, we have seen a pickled cow, an unmade bed, a demolished house, the lights flickering on and off, and a collection of mutilated Goya prints.

The root of this controversy is a widespread misunderstanding of the nature of contemporary art and an inability to see what the Turner Prize is really about. There seems to be a division in the art-consuming public between those who are genuinely interested in contemporary art and those who are in pursuit of a more canonical vision of the history of art. The first group can be seen swaggering around East London in their skinny jeans and lopsided haircuts on First Thursdays, chortling about the existential implications of the latest pile of sand to adorn a gallery floor.

The second group sticks to the beaten track, trawling through the National Gallery, droning on about Titian and lamenting the loss of “real talent” when faced with an exhibit in Tate Modern. These are the people who look at the Turner Prize through the lens of the Daily Mail Theory of Art that art is about skilful depiction in paint and marble. Just take a look at comments by Daily Mail readers for examples of this narrow-sighted, uneducated view of art.

If you insist on peddling this backward view of art, then almost any Turner Prize shortlist from the last twenty-five years will baffle you. You might have been enormously gratified, in 2003, to hear that Grayson Perry won for hand-made ceramic pots which he painstakingly painted by hand. But this quickly turned to shock when you discovered that Perry wears a dress, calls himself Claire and paints obscenities on his immaculate pots.

It is my guess that the people who are shocked by the Turner Prize are viciously ignorant of what art really is about. The Turner Prize is a reliable barometer for gauging the state of contemporary art. It is doing art and the public a great service by bringing to the fore that which otherwise normally resides within the forbidding clique of the commercial gallery system.

The other reason why the Prize is misunderstood is that people do not see it for what it is. The publicity stunts, headlines and artworld self-satisfaction that the Turner Prize proliferates are all a result of that fact that the prize is concerned with spectacle as much as it is with art. There is an insidious fear in the public that if the Turner Prize was about showmanship, showing off and a whole lot of banter, then we should have to admit that it doesn’t take art seriously.

This fear is unfounded and wrong, since the history of art is replete with grand acts of bravado and ambitions of spectacle. If you want a spiritually provocative depiction of the Last Supper, you only get Leonardo da Vinci to paint it all across your dining room wall if you want to show off. Velazquez’s monumental pictures of King Felipe IV, the Sistine Chapel, Duchamp’s infamous urinal, Carl Andre’s pile of bricks are all about art being spectacular. The Turner Prize merely capitalises on this tradition.

The greatest example of the art of spectacle in the Turner Prize was Martin Creed’s 2001 winner, The lights going on and off, which consists of literally nothing but the physics of light, but manages to be absolutely captivating. Essentially, Creed causes a lot of fuss about nothing, and as the momentum grew and the other nominees fell behind, the Tate raked in ticket sales as people fell over themselves to see nothing but an empty room with faulty florescent lights. It was brilliant, as both art and showmanship.

This year’s Prize is interesting precisely because it seems devoid of spectacle, but that is merely an illusion. A realist painter, a historically educated sculptor, a film-maker with a good eye for light and a playfully experimental painter do not give Emin and Hirst a run for their money. Shut out the noise from those who are alarmed by Karla Black’s floating ball of plastic or Hilary Lloyd’s indulgent male nudity and this year’s prize is comfortingly demure.

This, however, is the spectacle: the crushing banality of these four presentations is parcelled up and exported to the culture industry in a confrontational gesture that compels us to question whether contemporary art can really enlighten us about our lives.

Hegel famously pronounced the end of art because once philosophy had taken over, art could no longer speak to the human condition. But this year’s shortlist features artists whose work seriously engages with issues of consumerism, class struggle, urbanisation, as if to prove the continued relevance of art to human understanding. Probably the most shocking thing is that the exhibition this year is being held outside of London; at the Baltic in Newcastle.

The spectacle, then, is not in elephant dung or used condoms, but is in a brash rejection of the very idea that contemporary art has to be shocking in order to be interesting. The Turner Prize shortlist this year is centrally noteworthy for the fact that it emphasises the capacity of art to make us think about our sorry lives and the rotten world we live in, whereas in previous years it has shown how art makes us think about art.

This is most brilliantly achieved by Shaw’s paintings that present a grotty, miserable world of empty ambition and lost hope, but which nonetheless elicits a nostalgic affection for remembered places and a loyalty to personal history. The real spectacle will be if he actually wins the prize; if, that is, a seemingly traditional, realist painter walks away with the prize usually awarded for dressing up as a bear or singing a Scottish lament.

Daniel Barnes is a philosopher and art critic based in London, UK.

Photo credits: BALTIC gallery

(Clockwise, from top left)

Karla Black Persuader Face, 2011 (detail). Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne. Photo: Jonty Wilde. © the artist, Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Martin Boyce A Library of Leaves, installation view, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich Courtesy The Artist, The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich. Photo: Stephan Altenburger.

Hilary Lloyd Man, 2010. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London. © The artist.

George Shaw Poets Day, 2005/06. Courtesy Wilkinson Gallery, London. © The artist

Leave a Reply