Radical Aesthetics The View from Lebanon

New in Ceasefire, Radical Aesthetics - Posted on Saturday, April 23, 2011 0:00 - 2 Comments

By Daniel Barnes

A recent spate of exhibitions in London by Lebanese artists has demonstrated the enduring power of art to play an active role in heightening political consciousness. But why is art such an ideal site for political discourse?

There is a noble tradition of art and politics. The Miro retrospective at Tate Modern explores his lifelong refusal to concede to the Franco State by painting his way through resistance. Picasso’s Guernica, a tapestry reproduction of which hangs at the entrance to the UN Security Council room in New York, is an enduring monument to popular outrage at the barbarism of war.

Even Wagner, whose political views were almost entirely repellent, sincerely believed that art’s major purpose is to incite revolution. These days, we have Bob & Roberta Smith scrawling impassioned political slogans on canvas, currently addressing the impending AV referendum.

Contemporary art holds a mirror up to society so that we can scrutinise the unsightly blemishes that we otherwise fail to notice or complacently ignore. I have recently been struck by the ingenuity and intensity with which it is being pursued in Lebanon.

The political volatility of the Middle East and the Arab world has historically been a source of inspiration for art. Juliano Mer-Khamis, who was recently brutally murdered in Jenin, the Palestinian painter Ismail Shammout and Mona Hatoum, who has just presented her new work in London, are all fine examples of politically engaged artists.

In response to their own troubled past and the broader narrative of their beleaguered brothers and sisters, some Lebanese artists can currently be seen using art as a powerful tool in the struggle against oppression and injustice. They achieve a seamless fusion of art’s twofold imperative to convey urgent messages and to produce aesthetically interesting cultural artefacts.

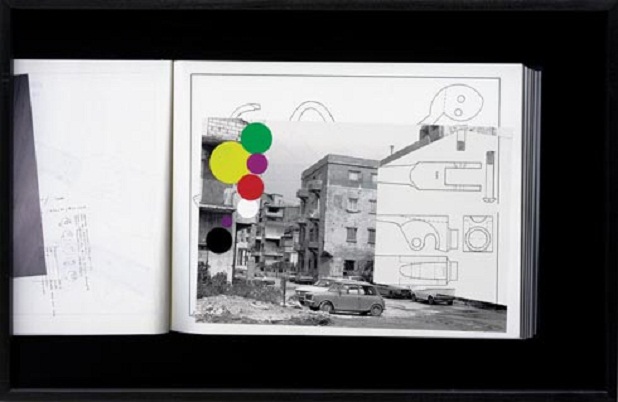

In his acclaimed Whitechapel show, ‘Miraculous Beginnings’, Walid Raad asked searching questions about how history is constructed. His eerie black and white photographs of the ruins of Beirut depict a ghost town entirely emptied of people and all signs of life, reminiscent of Atget’s photos of Paris that Walter Benjamin so admired.

In the series, ‘Let’s be Honest, the Weather Helped’, Raad superimposed coloured dots over images of ravaged buildings, trees and cars. He tells us that every night he walked the streets of Beirut collecting bullets and identifying their country of origin, which is denoted in the photographs by the colour-coded dots, announcing which countries were conspirators in supplying the munitions.

These stark images aspire to create a space in which the Lebanese Civil War can be considered objectively. Raad uses art to document history, to construct a narrative and encourage serious reflection on the causes and consequences of events.

However, there is a trick: the work is produced by Raad’s fictional alter-ego, ‘The Atlas Group’, and all the images that claim to be of war are in fact of house-fires and car accidents. The whole show is an elaborate ruse that aims to question how history is constructed and to assert that documentation is a poor substitute for lived experience.

Rabih Mroué’s first UK solo show, ‘I, the Undersigned’, was initially conceived as a reflection on the relation between historical events and personal lives. It was Mroué’s attempt to reconcile his role in the Lebanese Civil War with the stoical resilience of his family and fellow countrymen.

Recent events in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain and Libya, however, moved Mroué to reconceptualise the entire show in a move away from the indulgence of the individual towards a robust solidarity with the masses. Consequently, he changed the title at the last minute to ‘The People are Demanding’.

This interweaving of the personal and the historical, of daily life and exceptional circumstances, continues throughout the show, most evocatively in Grandfather, Father and Son. The work relates a series of episodes that occurred in Mroué’s family during the years of the Civil War. It is accompanied by immaculately hand-written pages of equations from his father’s book on Fibonacci, which, he tells us with the profound paranoia of a war-torn man, the Israeli invasion of 1982 was designed to obstruct the completion of.

A floor-to-ceiling display of all 8,000 cards that catalogue his grandfather’s library, with numbers, authors and titles in feverishly written Arabic script, makes for a sobering reminder of the need to create order out of chaos.

Despite all the war, terror, human catastrophe, this show is far from stark or depressing: it is infused with tenderness in Mroué’s affection for Lebanon and the love of his family; it is replete with reassurance that there is renewal and growth in the ruins.

Similarly, Raad’s work neither glamorises war nor makes a rhetorical gesture of its horror, but rather presents it dispassionately as a cold fact of life which must be reflected on as such in order to find solutions. These two artists ask what we can do to change these grim states of affairs by representing them in such a way as to induce aesthetic wonder and critical reflection.

Both Raad and Mroué are dealing with urgent issues, but the question remains as to why it is up to art to pose these questions. There are three main reasons why artists have a unique power to arouse political consciousness in desperate times.

Firstly, art is primarily valued as an aesthetic phenomenon, whether for pleasure or entertainment, which means that people already have a compelling reason to accept it into their lives, giving its political agenda a solid advantage.

Secondly, artists are a diverse group of people who are bound only by the conventions of the artworld; at most, they share national and cultural identities in virtue of accidents of birth. But they are not inextricably bound by an ideological protocol, so artists are free to express whatever point of view they choose.

The recent case of Ai Weiwei, who has disappeared in custody of the Chinese authorities, demonstrates that this freedom sometimes comes at price, but it is the reason why we are so inclined to listen what artists have to say. Whilst artists have a voice and a channel of expression, it is fragile and precious.

This is pertinent when considering the fact that, despite the success of Lebanese artists abroad, it was announced three weeks ago that Lebanon is no longer to participate in this year’s Venice Biennale. Georges Rabbath, curator of the Lebanon pavilion, is planning to go ahead with the country’s presentation unofficially on the fringes of the event.

The project, Lebanon As a State of Mind, invites people to come up with a new constitution for Lebanon in order to encourage participation in the construction of a new meta-narrative for the country.

This illustrates the third reason why art and politics go so well together: art fosters a sense of community through active participation, whether in the process of creation or the act of reception. The result of political art can thus be genuine political engagement.

The Lebanese seem to have turned to art precisely because other political channels are too impoverished in creativity, innovation and radical freedom of thought to bring about serious, efficacious critical reflection.

The example of Lebanon has demonstrated how art really can illuminate political issues through the intimate melding of aesthetics, freedom of expression and active participation. Art might not quite save us from our own inevitable catastrophe, but it can inspire us to think critically, even radically, by dressing the world up without concealing the ugliness.

Daniel Barnes is a philosopher and art critic based in London, UK.

2 Comments

Radical Aesthetics The View from Lebanon – Ceasefire Magazine « Latest Search

[…] Visit link: Radical Aesthetics The View from Lebanon – Ceasefire Magazine […]

“A recent spate of exhibitions in London by Lebanese artists has demonstrated the enduring power of art to play an active role in heightening political consciousness”