The Natives of Canada Ghosts of History

Ghosts of History, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Monday, October 13, 2014 18:08 - 6 Comments

By Xain Storey

“We also have no history of colonialism” – Stephen Harper, current Prime Minister of Canada

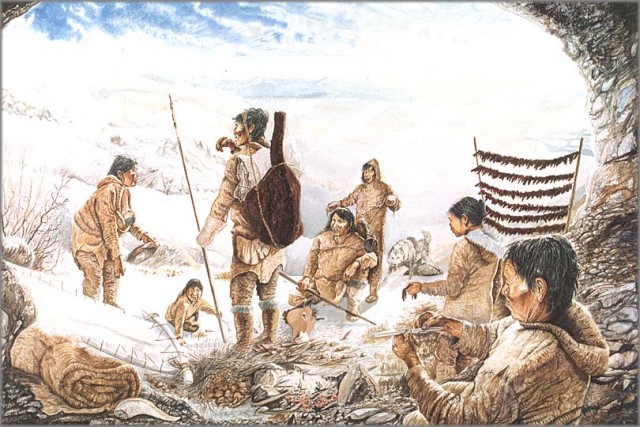

From an aggregate of paleontological, anthropological, genetic and linguistic research, it is hypothesised that, among other theories, the first Humans in America migrated from Siberia during the last glacial period, across an exposed continental shelf in the Bering Strait, between 30,000 and 14,000 years ago.

Today, Canadian Aboriginals are categorised into three distinct groups, totalling 1.4 million people. These are the First Nations, the Inuits, and the Métis people of Canada. Whilst the First Nations include members of all indigenous nations descending from Palaeo-Eskimos, the Inuits’ ancestors were the Thule people, who originated in Alaska, from where they travelled to Canada and Greenland between 200 BCE and 1300 AD. The Métis are descendants of both First Nations and European colonists (emerging in the 18th Century, when French fur traders married Native women), but they are defined by their unique culture, taken from both Native and French customs (which may explain why they are called Métis, the French word for ‘mixed’).

Prior to Columbus’s arrival, Vikings established small colonies in Eastern Canada from 980 CE until around 1050 CE, marking the first European contact with the Americas. Before the European invasion, the population of Canada numbered between 500,000 and 1 million natives. Whilst Vikings had contact with Aboriginals (whom they referred to as ‘Skrælings’), it is unknown whether the decline of the Norse colonies was due to conflict or environmental unsuitability, though there is evidence for both.

In 1497, Giovanni Caboto sailed to Newfoundland in Eastern Canada, calling the indigenous people ‘Indians’, as Columbus had done before him. Following this, contact was intermittent up to the late 16th Century, where fur traders and fisherman were active across most of Eastern Canada, which the French claimed as ‘New France’ (at this time, ‘Canada’ was one of five provinces within New France).

The Beothuk were one of the first indigenous groups devastated by European imperialism, as Portuguese, French and British settlers encroached on their homes in Newfoundland, exploiting it mostly for lumber and fish (the Mi’kmaq tribe also harassed the Beothuk, but not to the extent of genocide). Early invaders captured them, sometimes for rewards of 50 pounds each, sold them into slavery, or put them in European exhibitions like animals in a zoo. The Beothuk people tried to avoid the White men, who, by the 1700s, had built settlements all over Newfoundland, deracinating the natives to the point of resource deprivation and, eventually, extinction in 1829 at the hands of British colonists and military.

Whilst the Portuguese had made contact with native land before the French, they abandoned their settlements due to the cold climate, moving further south. From 1534 onwards, both Britain and France were further impinging upon Aboriginal land. By the early 17th Century, French and British companies had begun setting up posts along the Atlantic coast for their fur trade and fisheries. From 1629, the Scottish also attempted to colonise Canada, specifically Nova Scotia (Latin for ‘New Scotland’), but were forced to abandon their settlements, having been driven out by the French by 1632. However, the Scots remained integral to the British invasion, settling in the Maritime Provinces, originally home to the Mi’kmaq, as well as emigrating in droves, resulting in further dispossession and socioeconomic suffocation of the indigenes.

From the 17th Century onwards, a large influx of French citizens began to invade the homelands of the natives and, with them, came smallpox, influenza and measles, which reduced the population of the Aboriginals in New France by over 100,000 (the Huron population was halved as a direct consequence of French settlement). Meanwhile, the French population had increased from 100 in 1627 to over 60,000 by 1754. However, this was significantly smaller in comparison to the population of British colonies, numbering around 1 million, as well as over 300,000 slaves.

The French brought Africans to their colonies as early as 1628 (Olivier Le Jeune was the first known African slave brought to New France), and their enslavement remained integral to the creation of colonial Canada. Around 4,000 slaves existed before British rule, mostly Africans and Aboriginals. The invaders maintained somewhat ‘peaceful’ alliances with the natives, except for the Iroquois, who they regularly fought until the Peace Treaty of 1701. Sir Raymond de Nérac explained the French’s approach to natives in a memoir, stating that:

“(T)he politics and consideration we must have for the Savages to keep them loyal are incredible…to serve effectively, a commander must turn full attention to earning the trust of the Savages in his area. To do so, he must be friendly, he must seem to empathize with them, he must be generous without extravagance, he must always give them something.”

Throughout New France, assimilation policies were implemented in schools attended by indigenous children, in order to remove their ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, and raise them with French customs. This attempt was mostly a failure, as it was “…very difficult, nigh impossible, to make them French or civilize them.” Furthermore, the French, determined to placate the natives and ensure their acquiescence to their paternalistic state, ended up learning their languages and culture. Nonetheless, White supremacy remained a prevalent ideology of the invaders, who believed that the ‘savage’ natives were in need of European civilisation. This was nothing less than barbarism cloaked beneath the moral facade of progress and industry, as well as the abuse of Christian doctrine.

Though not without conflict before the advent of European settler-colonialism, relations between various indigenous tribes were embittered by it, due to land and resource appropriation which imperilled the survival of tribes and, in turn, compelled them to compete with one another over the enforced scarcity to ensure their survival. The French and British appealed to different Aboriginals’ needs for autonomy, by promising them a reduction in colonisation, which the British victors later reneged on. The Iroquois League allied with the British, during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) against France and the Wabanaki Confederacy, culminating in the cession of New France (and all other French territories in North America) to Great Britain, and the second wave of colonialism of what is known today as Canada.

Whilst the British originally recognised the rights of the natives, the Revolutionary War and the creation of Indian reserve lands both caused fissures in the indigenous communities, dividing and effacing their cultural roots, and pushing them further into deleterious socioeconomic environments that still exist today, and which have engendered manifold behavioural/health dysfunctions, such as alcoholism, addiction, and suicide.

In the 19th Century, native land was being given to British invaders, who would exploit it for the resource abundance. This practice became official policy by 1830, where the Empire considered the Aboriginals an inconvenience. Despite the codified acknowledgement of native rights, the systemic racism thrived, reaching its zenith with The Indian Act of 1876, which gave the government control over indigenes’ lives, declaring them unfit to manage their own affairs and thus in need of assimilation into Canadian society.

Legislation was subsequently passed to ‘civilise the Indian’, giving birth to the ‘Indian status’ and the residential school system, which mandated the attendance of native children at boarding schools. Over 150,000 indigenous children attended these schools until the 1990s, and were subjected to inimical conditions: forbidden from speaking their native tongues, forced to convert to Christianity, and subjected to physical/sexual violence, malnutrition experiments and rampant tuberculosis. Mortality rates among native children ranged between 40% and 60% in such schools.

In 1920, the superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs stated his plans for the natives, “I want to get rid of the Indian problem…. Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question”. From the 1960s to the 1980s, tens of thousands of Aboriginal children were kidnapped and adopted into non-Aboriginal families. Furthermore, from the mid-80s to the present day, over 1,200 native women and girls have gone missing and/or were murdered, in great disproportion to the figures for non-indigenous women, yet the Canadian government has continued to ignore this intersectional crisis.

In truth, there are innumerable examples of the horrors committed in the region by the colonial powers in the past that continue to perpetuate the debility and cultural effacement of the First Nations, Inuits and Métis people today. That none of these atrocities have been recognised as genocide to date is astonishing. That 500,000 natives still live on reserves, blighted under the same, corrosive conditions imposed on them during British rule a century ago, is a disgrace.

Isn’t it time to change that? Isn’t it time to end the silence on Canada’s legacy of colonialism?

6 Comments

Rizwan Iqbal

seema dehalvi

An enlightening article, makes you really think that First Nations, Inuits and Métis people have suffered enough and deserve justice!

Looking forward to your next article.

Jamiyah

wow, this article was extremely enlightening. I had no idea about any of this. Thank you! Please continue this series

johnberk

This short introduction to the history of the aboriginal people of Canada made me think about whether it was possible that Harper said such a stupidity. It somehow feels that he would fit better into the 1920s, rather than to the contemporary politics. I’m glad that you mentioned forced adoptions, and other horrors the First nations were put through. I felt ashamed when I read a Gabor Mate’s book In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, where he talks about his patients, who had described to him the horrors they had to go through in their lives due to the fact they were born with different cultural background. It is also sad to see that. We should feel ashamed and try to rebuild the confidence between us, instead of buying handmade things on flea markets or using them as some pseudo-culture and almost nonexistent Canadian peculiarity.

Racism is… | Media Diversified

[…] is theft and the thieves then lying about it. Racism is not having a home, living in a state of rootless […]

Denis Thériault

Tu sembles avoir des fausses histoires du début envers les Acadiens français et leurs amis autochtones en 1604. Je comprends, tu es anglophone !!!

Incredible article and series.