A Maze of Mazes: On Bob Dylan Arts & Culture

Editor's Desk, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Wednesday, April 1, 2009 13:13 - 0 Comments

“I was sort of trying to find a place to pound my nails, y’know.”

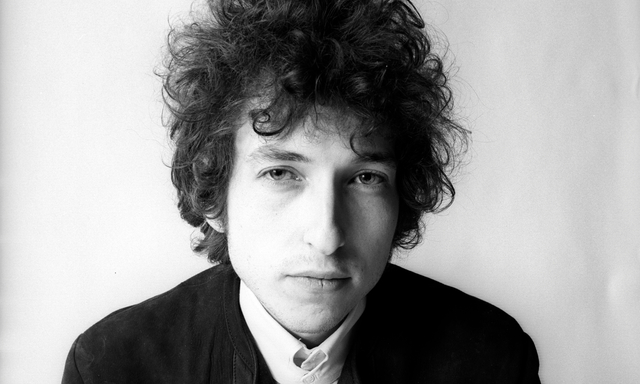

Over the decades, Bob Dylan has been many things to many people: sage, buffoon, trickster, mercenary, genius, madman, charlatan, oracle, fraud, false prophet, true poet, über-chameleon, master of the recherché art of wrong-footing both your disciples and your enemies and, quite possibly, the major recording artist with the worst singing voice of all time. Dylan is a maze of mazes, a glorious shrine to the wonders of the modern human soul.

In April this year, Dylan released his latest album, Together Through Life. The reviews have been glowing but their mood unmistakably sentimental, for it is now clear Dylan has properly entered what Edwaed Said would’ve called his ‘late style’ period, an era now marked by a serene longing for the past he never quite belonged to: that of folksy bluesy Americana; the pure jagged sound of the American heartland.

The move is not entirely sudden. His previous three albums: ‘Time out of Mind’; ‘Modern Times’ and ‘Love and Theft’ all wore their nostalgia badges proudly, to great effect. Now that Dylan is approaching seventy, apprehensive glances are being thrown towards the future, and the obvious question persists in the mind: will Dylan still matter in this twenty-first century of civilisational gloom, post-moral uncertainties and cultural coarsening? The clues to the answer might well lie at the very beginning.

In one of his earliest interviews, conducted with the legendary broadcaster and raconteur Studs Terkel, a 20-year-old Dylan tries to explain his metier thus: “I was sort of trying to find a place to pound my nails, y’know.” This remarkably violent imagery is not accidental. The Dylan ‘philosophy’ – if there ever could be such a thing – might quite be summarised as “existence is violence”.

In one of his earliest interviews, conducted with the legendary broadcaster and raconteur Studs Terkel, a 20-year-old Dylan tries to explain his metier thus: “I was sort of trying to find a place to pound my nails, y’know.” This remarkably violent imagery is not accidental. The Dylan ‘philosophy’ – if there ever could be such a thing – might quite be summarised as “existence is violence”.

Indeed, the implied neutrality towards institutions, systems and ideologies might well explain Dylan’s obsession with shape-shifting, including his notorious “great escape” – or defection, or betrayal – from the ranks of the US protest movement in the 60s, infuriating many of his devotees and comrades.

Dylan’s attempts over the ensuing four decades to escape from the “voice of a generation” tag have been unmitigated failures, as any cursory glance across the thousands of column inches of media coverage will tell you: a rare and rather delightful instance of the opportunist being soundly beaten at his own game.

In all likelihood, Dylan will continue to endure right into the next century, not just because his poetry is now a national treasure, but mainly because he will always, above anything else, be the defining epitome of the self-denial/self-renewal duality of the modern American soul.

Leave a Reply