Lebanon: Even freedom of expression, our last bastion, is now under threat Comment

Editor's Desk, New in Ceasefire - Posted on Friday, September 18, 2020 11:45 - 0 Comments

By Naji Bakhti

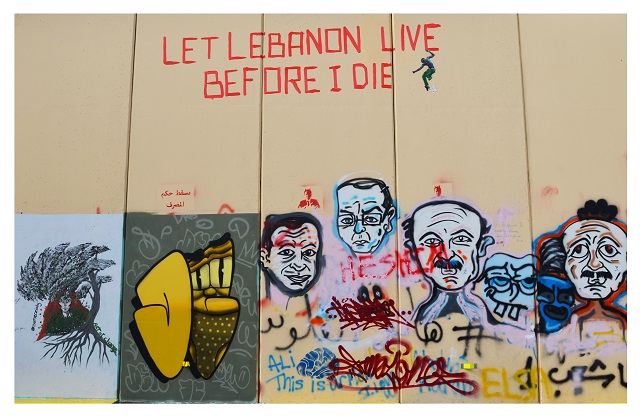

Feb, 2020. ‘Let Lebanon Live’, a small portion of one of many ‘Revolution Walls’ of art and graffiti seen in Beirut.(Credit: Mary Crandall, licensed under Creative Commons)

To hear a Lebanese man or woman speak the language, you might be forgiven for imagining the speaker’s lips as two like-pole ends of rattlesnake magnets, intent on repelling one another. The words slip out even as the bottom lip dances around the upper one, while the jaw bounces forever away from the rest of the face. This is why, when I heard my fellow countrymen and women on the eve of October the 17th, 2019, demand with a distinctly robust, assured tone, an end to the thirty-year corruption and mismanagement of the political elites, I considered for a moment that this might be the collective cry of a neighbouring nation – one with a more conventional dialect. Then I remembered that the neighbouring nations are Syria and Israel, where rallying cries like these are not encouraged – as the Syrian people can attest throughout the past decade of civil war, and the inhabitants of Gaza will tell you if only they had the electricity, internet or freedom of movement to do so.

The list of crises in Lebanon itself is long: water-shortage, power-outages, rampant corruption, serial mismanagement and incompetence, unbounded nepotism, inflation, economic collapse and, of course, sectarianism. Restrictions placed upon freedom of speech, however, was not supposed to be one of them. After all, Lebanon had always prided itself on being a beacon of light in that regard within the region. Red flags were raised recently, when state prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat instructed the Central Criminal Investigation Bureau to investigate social media posts which insult the person of the President of the Republic of Lebanon. Not long after that, a crackdown on activists ensued, with state means employed to arrest or detain outspoken voices such as Michel Chamoun, Kinda Al-Khatib and Gino Raidy.

In another assault on civil liberties, Judge Mohammed Mazeh issued an order banning the media from interviewing or hosting the U.S. ambassador, Dorothy Shea, who had earlier criticized Hezbollah publicly, on the grounds that she was inciting unrest and intervening in local matters. The ruling was taken with a pinch of salt, not least because the judge’s last name literally translates to ‘joke’. The erstwhile Information Minister has since denied the validity of the ruling, but the absence of an independent judiciary remains far from a laughing matter. Television networks have not been immune to this crackdown either, with MTV Lebanon, a Lebanese network which has been a vocal critic of the Lebanese ruling class, being banned from covering events within the presidential palace.

I will not pretend that Lebanon has always been an oasis for freedom of expression. Under Syrian hegemony during the post-civil-war era, Lebanese journalists and politicians often paid with their lives (Samir Kassir) or their limbs (May Chidiac) for daring to speak out against Syrian rule. Lately, Hezbollah followers, for instance, have taken to readily chasing someone around the country in a bid to extract an apology – usually violently – for a perceived insult against their hallowed leader, Hassan Nasrallah; and then posting a before-after cut of the video on YouTube. Nor do religious leaders, who exert significant influence upon Lebanese politics via confessionalism, shy away from expressing their sacrosanct opinion about a work of literature or art which denigrates Jesus or Mohammad. This can occasionally lead to the banning of novels, as happened to Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, which would still be found in bookstores anyway because of the aforementioned incompetence. Dan Brown made the mistake of suggesting that a fictional Jesus might in fact have had intercourse before he was thirty. (Mind you, if you were going to ban a book, then The Da Vinci Code would be my pick too).

I do not mean to trivialize the above instances of censorship and violation of freedom of expression. Rather, I mean only to suggest that the Lebanese have generally found a way to circumvent or openly condemn these acts. Except now it seems that the president via the apparatus of the state is, directly or indirectly, making that very same threat which had formerly been the preserve of Hezbollah militia, oppressive foreign powers and decaying religious authorities. It would be wrong to say that the octogenarian, former general has the full force of the law behind him. First, the law is not behind him, as the Lebanese constitution guarantees the right to freedom of expression. And second, the law in Lebanon does not generally operate in full force, or at all in some instances.

Yet, to witness the thin-skinned president, and his Hezbollah allies, so blatantly dismiss the right to freedom of expression using the instrument of the state remains noteworthy. If only because, not six months ago, the Lebanese had stood outside the house of parliament and called on him in no uncertain terms, via a passable impression of a slightly less slack-jawed dialect, to resign. The government fell then. The president did not. His son-in-law, the former minister of foreign affairs, was the subject of a hilarious ditty to do with the latter’s mother. This led to a surreal scene in the midst of the revolution in which Gibran Basil – Lebanon’s Jared Kushner for the uninitiated – stood outside the presidential palace, surrounded by a small group of loyalists and apologized to his own mother on live TV, on behalf of the Lebanese public. This was Eminem in ‘Cleaning Out My Closet’, if the rapper were shorter, less articulate and had long ago blown his one shot, one opportunity.

In the wake of last month’s harrowing port explosion on the 4th of August, which claimed the lives of hundreds and the homes of hundreds of thousands, the second government in sixth months fell as the Lebanese swarmed the house of parliament and downtown Beirut, angrily demanding accountability and change, only to be met with teargas and rubber bullets. Dozens of protesters broke into the foreign ministry and burned a framed portrait of President Aoun, who embodies the corrupt ruling class responsible for the dire state of the country. The retired former army officer who had led the stunt was arrested and his compromising picture in the back of a car circulated on social media: further evidence, if any were required, that the security forces now serve as the president’s own personal appendage. Once again, the president held on to his seat citing fears of a ‘constitutional void’ and concern over the peaceful transition of power.

Freedom of speech is admittedly not high on the list of priorities for the Lebanese at this moment in time, with the Lira having lost more than seventy percent of its value since October, the price of meat having tripled, and fuel-shortage intermittently rendering the country near pitch-black. It is understandable, therefore, that many of us should be thinking more about what enters as opposed to leaves our mouths. A hungry man will lose his appetite for speech, or at least that is what the sectarian, dynastic warlords are banking on.

One such Lebanese man shot himself outside of a Dunkin’ Donuts on Hamra Street, a popular High Street in Ras Beirut. He left a note which simply read “I am not blasphemous…”, a line from a Ziad Rahbani wartime song which ends with ‘but hunger is blasphemous.’ The man had also left a copy of his clean judicial bill – suspecting, not unwisely, that the ruling parties might attempt to assassinate his character and cast doubt upon the integrity of his motives. He left a Lebanese flag too, propped up against a potted plant by the rows of tables and chairs scattered across a well-trafficked pavement with patches of gum stuck to the tiles and cigarette butts and dirt and, now, the blood of a man who hungered for food and had his final word and left.

Leave a Reply