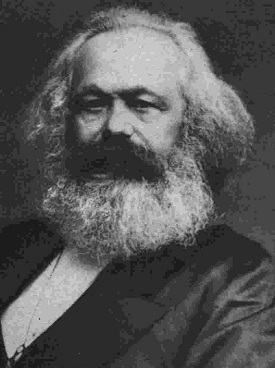

In Theory – Karl Marx’s fetishisms

Columns, In Theory - Posted on Thursday, September 23, 2010 0:05 - 5 Comments

By Andrew Robinson

By Andrew Robinson

We are surrounded by objects which have (at least potentially) the status of commodities, but what is this status and how does it relate to social life? This article will explore the most famous and influential response to this question: Karl Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism. This is not a theory which exists in a void. Commodity fetishism is central to Marx’s account of alienation and hence to his ethical critique of capitalist society, as well as to his structural theory of the functioning of capitalism. It is, according to Marx, the most universal expression of capitalism. Hence, in understanding capitalism, it is useful to look again at commodity fetishism.

To make a fetish of something is to treat it as if it has powers which, at least on its own merit, it lacks. As we shall see, this does not mean that a fetish is a simple illusion. Nevertheless, in commodity fetishism, commodities – physical objects which are bought and sold – are take to have a characteristic they do not in themselves have. As early as the 1844 Manuscripts, Marx argued that the products of labour tend to escape people’s control in capitalist society, leaving people estranged from the products of their own creative activity. In Capital, Marx takes this argument further, arguing that the ‘fantastic form’ of commodities is the basis for alienation. Commodities in capitalism take on a second, additional set of characteristics alongside their physical characteristics as items with certain properties and uses. While their ‘use-values’ and physical attributes are not mysterious, commodities also take on characteristics of inherent exchangeability which are quite alien to their physical nature. Furthermore, their values are not, according to Marx, set arbitrarily; they come about systematically, seeming to be natural attributes of commodities. Such values are real, but not inherent to commodities.

This equivalence is the trick of commodity fetishism, for the objects related as commodities are not inherently equivalent – they have different uses, different sizes, heights, masses and so on. Thus, commodity fetishism renders very different kinds of commodities equivalent. Commodities can be bought and sold for exchange-values which are quantifiable – they appear as numbers (prices). It is this equivalence which makes exchange possible. According to Marx, since their relations are not arbitrary, this means they must have an attribute in common through which they are compared. Capitalism is unusual among social systems: while all systems connect incommensurable activities, capitalism alone does so by rendering such activities equivalent. This primacy of equivalence is one of the reasons the currently fashionable view of capitalism as absolutely deterritorialised is flawed. For capitalism to function, the huge range of different objects which can exist as commodities must be reduced to a single, reductive scheme of equivalence, by means of command. Money, the universal equivalent, functions in this field as a master-signifier, as argued by Jean-Joseph Goux. In other words, money integrates the social field, rendering the other objects equivalent. Once established, it allows effective economic coordination without any kind of decision-making, either democratic or authoritarian, at the level of the entire system (as opposed to the specific company or enterprise). Commodities serve as the link between people and thus allow the allocation of people and things to social production without any kind of planning.

The attribute Marx thinks that commodities have in common, which allows them to systematically attain value, is that they express the ‘congealed’ labour of workers. Exchange-values ultimately follow from the amount and type of socially-defined labour that goes into making a commodity. Of course, this simply moves the problem, because labour, like produced goods, is actually diverse and not comparable. Labour is made comparable by reducing it to one and only one of its many characteristics: the characteristic of being abstract human labour-power. Once the value of labour has been imposed, it makes sense that it could be expressed in the value of commodities. Hence, commodity fetishism is only possible in a social system where labour is socialised. The treatment of all labour as socially equivalent rests on a process of abstraction which not only ignores differences among types of work, but also silences the life-experiences of workers. Workers are formally related through the commodity-form only indirectly, in their contracts with bosses and not their relations with other workers. In practice, of course, workers are engaged in socialised production. Capitalism is ultimately imposed on society only by means of violence – known as subsumption, or accumulation-by-dispossession. People are forced into wage-labour by the destruction of other social forms such as subsistence economies, and a continuing violence to prevent such alternatives from re-emerging. Some people constantly challenge this coercion into capitalist work by strategies such as ‘autoreduction’ and ‘dole autonomy’, and capitalism seeks to suppress such challenges by renewed violence. Also, there are constant struggles over the wage capitalists have to concede to workers in return for imposing the commodity-form, both directly as payments and as a social wage, such as the welfare state.

Capitalist society is simultaneously individualist at an ideological level, and coercively collectivist in its underlying functioning. In commodity fetishism, people appear independent, but in fact are highly dependent on the world of commodities, which for instance, can take away people’s jobs due to changing prices or demand. Hence, commodity fetishism masks what is in fact a social compulsion and a distribution of work. Indeed, it masks the fact that, far from being free producers selling their labour, people are subject to a kind of forced work. It conceals both the interdependence of people in capitalism and the coerced nature of their organisation. As a result, it integrates people both vertically – as workers subordinated to bosses – and horizontally – distributed among different work tasks – without creating direct horizontal relations among producers at the level of the system itself. Instead, each worker is subordinate to the world of things, which embodies the integrative force of the entire system. Furthermore, it is through the commodity-form that the illusion is created that capital can reproduce itself, that investing money in something can produce more money – a step which should be impossible in an equivalential system. This supposedly self-expanding money is only possible because the commodity-form disguises the exploitation of workers.

Commodity fetishism creates ideological boundaries between what can be seen and what cannot. Marx argues that commodity fetishism makes relations which actually occur between workers and capitalists, the producers of commodities, appear to be relations between the ‘things’ which are produced. Commodity fetishism is in particular the means by which the role of workers in production is disguised. Capitalist accounts don’t talk much about workers or producers as a distinct group, but producers are able to appear in capitalist accounts as owners of commodities, for instance, as people hired to sell their labour. The second set of characteristics of commodities arise from the fact that they portray characteristics of work as characteristics of the product of work. Through the movement of commodities, labour becomes invisible. For instance, products seem to appear in supermarkets as if my magic, put there by a process of labour and transport which remains invisible. Marx believes that this peculiar invisibility of labour only arises in capitalist society – it did not occur in earlier societies, however class-divided these may have been, and would disappear in any future alternative society. As Billig argues, this invisibility makes possible enjoyment of capitalist consumption by hiding exploitative conditions of production. Demystification of the ideological nature of commodities is necessary, but not sufficient, to destroy capitalism. Ultimately, commodity fetishism could be destroyed only if the entire form of society of which it is the integrative pole is transformed.

In commodity fetishism, people have an experience of being controlled by the activities and movements of inanimate objects. For instance, people are compelled or bribed to move between jobs by the changing relative values of different commodities. This is not simply false consciousness. We are in fact pressured from outside, people do in fact buy and sell commodities for money, and phenomena such as commodity exchange-value actually exist socially. This pressure does not actually come from commodities, but commodities act as the way in which the pressure appears. In capitalist society, the only way people can affect other people’s productive activity is indirectly, through changes in the relations among commodities. In Gerry Cohen’s account, the illusion is not in assuming that commodities have value, but in believing that this value is an attribute of commodities. Commodities do in fact have value, but only as a result of social relations; they do not have it in themselves. Hence, commodities are socially constructed: they have a status which is real in its effects, but which is a matter of status being assigned to them, much like putting someone in an official uniform. In many ways, people in capitalism are in the worst of both worlds: individualised enough to be denied social support, and yet vulnerable to external forces over which they have no individual control. This creates the ‘possessive individualist’ type of subjectivity – ostensibly free, yet also ‘responsible’ to imperatives derived from impersonal forces and relations among things (to be employable, wise with investments, credit-worthy and so on).

The status of commodities is rather mysterious, because they are at once real and fictional. A fetish is an ‘appearance’, but not an illusion. Unlike an illusion, it doesn’t vanish once someone realises it is an appearance. It does, however, conceal the underlying reality, which, once recognised, makes commodities cease to be mysterious. An appearance in this sense is distinct from the underlying essence or reality, which occurs at the level of the social relations which create the appearance. Through the appearance, certain things come not to be seen. Authors such as Bertell Ollman and Michael Billig argue that Marx’s account implies a kind of collective forgetfulness in capitalism: the system looks natural and unchangeable because the contestable social relations on which it is based are concealed. This concealment is sustained by habit. In many ways, however, fetishism is less an illusion than a founding belief which is necessary for an entire social order to function. It is something people have to believe, or act as if they believe, for the rest of the system to hold together. Commodities have value only because people (not just particular people, but all the people taking part in exchange) act as if they do. Nevertheless, people are forced to continue to act as if they do – even if they see through the mystification – for as long as they remain trapped in the system based on this assumption. Hence, fetishism is a way of organising social relations and not only an ideological perception of them.

The theory of commodity fetishism has been taken in a number of directions by other authors after Marx. According to Massimo di Angelis, whereas capitalists see fetishism as objectivity, workers experience fetishism directly, as a process whereby their activity is turned into objects. Di Angelis argues that commodity fetishism is basic to a ‘class understanding of economics’, providing the basis for understanding exploitation and capital. Only through the medium of commodity fetishism is labour rendered an activity for others, and hence exploited. More broadly, commodity fetishism can be seen as entailing ‘reification’, the misrepresentation of social relations and processes (becoming) as fixed things (being). The Hungarian Marxist George Lukacs argues the matrix or source of reification in general is commodity fetishism. From the initial reification stem a whole range of others, from misrecognising political relations of domination as laws and institutions, to imagining people’s situated social action to be the result of innate character-traits. This interpretation of Marx reaches its apex in the work of John Holloway, for whom the replacement of doing with being is the key dimension of capitalist oppression. For Holloway, every rejection of the separation of ourselves from our agency is a form of rebellion against capitalism, a rebellion which is, in the first instance, the negation of this separation.

There are also critiques which, while drawing on Marx, challenge his account of commodity fetishism, especially its applicability today. For instance, Jean Baudrillard argues that sign-value is now more important than use-value in creating commodities. Designer brands aren’t worth more because they’re more useful, but because of the social status they give or the impressions they convey. But they are given these status values in part because of their cost. This puts fetishism on a different level: the system ceases to attach additional elements to objects with independent uses, but rather, feeds back the fetish into the uses of the objects themselves. Another line of critique comes from Antonio Negri. In his 1970s work, Negri argued that the law of value has stopped working. The reason for this is that there is too much unpaid labour, as a lot of social activity outside the workplace is now productive – think for instance of housework and childcare, which are normally unpaid, but are vital to the reproduction of capitalism. Of course, commodities still have values, but Negri thinks they increasingly have values which are arbitrarily assigned to them, rather than derived systematically from similar characteristics of labour. As a result, value is imposed by command rather than exchange. This might not be a big change, since as we saw above, the value of labour from which commodity values derive was already imposed by command.

In my view, commodity fetishism is a useful concept in many ways. It depicts effectively the relationship between apparently mundane everyday practices and the forces of systemic integration in capitalism. It is extremely useful as a way of thinking about the internal logic of capitalism. But does it tell the whole story? While capitalism is ever more globalised and intrusive, I suspect that we do not – and cannot – live in an entirely ‘capitalised’ world. For one thing, the moment capitalism turns its back, other forms of life (both emancipatory and conservative) reappear – social networks, subsistence, local identities and so on. For another, capitalism depends on the state to keep it in existence, and the state, while also fetishised in its own way, has a distinct oppressive logic of its own, more about control and ‘security’ than exchange. In addition, the theory of commodity fetishism is limited in its ability to deal with the primary alienation of humanity and nature which underpins capitalism. This said, it is not clear that a theory of commodities should explain all these other things as well. Commodity fetishism is conceptually valid if understood as one of a range of social logics operating in a conflictual and hybridised social field – indeed, as one of the most important today – but it becomes more problematic if it is taken as the last word on social life. Even within Marx’s theory, it is only when supplemented by ideas of class struggle and revolution that it becomes a transformative concept.

Andrew Robinson is a political theorist and activist based in the UK. His book Power, Resistance and Conflict in the Contemporary World: Social Movements, Networks and Hierarchies (co-authored with Athina Karatzogianni) was published in Sep 2009 by Routledge. His ‘In Theory’ column appears every other Friday.

5 Comments

Alex

Andy

I’d be interested to hear more about that argument. The terminology is certainly religious (“fetish” was originally a not very polite term for animist totems or icons) but there’s the problem of the base-superstructure dichotomy – commodities don’t cease to have value, or social force, because people stop believing in them but God, being for Marx ideological, would surely if demystified much like a Stirnerian spook? Or are you suggesting more of an Althusserian co-constitutivity of ideology and economics? – If you don’t know it yet, have a look at Peter Rigby’s work on tha Maasai – Rigby makes an argument in concrete terms that what appear to be religious practices, customs and so on are actually part of a moral economy which is a way of sustaining a particular production system. Mudimbe accuses Rigby of being reductionist though. Personally I think a lot of religious practices are bioenergetic practices.

Alex

I’ll send you the chapter when its done, but its not suggesting the system would disappear if we stopped believing it. I’m suggesting something more along Feuerbachian lines and associated with his theory of alienation, through Walter Benjamin, Agamben and a few others in theology and religious studies who have attempted similar things – including Philip Goodchild’ The Theology of Money which shows how money is truly the ‘God of commodities’ that Marx speaks that structures belief, following and completing Sorel.

Marx (1865) “On the Fetishism of the Commodity” | Cheryl Williams

[…] to Video | Summary | Karl Marx’s Fetishisms | On Cultural […]

Commodity, fetishism and still life – Linda_Pipira

Very, very good.

“A commodity appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood. Its analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”

For me anyway, Marx’s critique of commodity cannot be separated from his critique of religion as I am desperately trying to finish arguing in my dissertation!